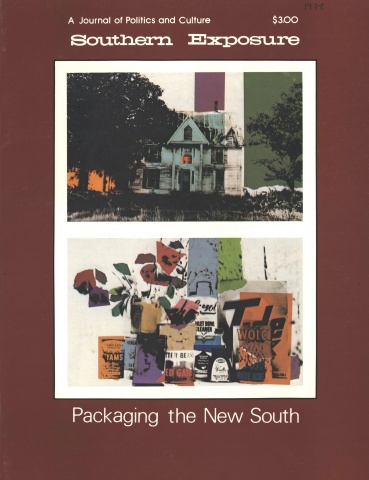

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

The hottest selling postcard these days in Mingo County, West Virginia, shows the railroad station in the county seat the day after the April 4th flood. The roof of the building and a sign saying “Williamson” are the only landmarks visible above the floodwater.

The steady rain in the first week of April, 1977, swelled rivers and creeks throughout the Appalachian parts of West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee. Even for people in a region with a history of chronic flooding, the magnitude of the disaster that followed was difficult to grasp. Thousands of people were left homeless, entire communities destroyed, roads and buildings were covered with six inches of mud.

Despite a 44-foot flood wall which separates Williamson from the Tug River, the water that poured from its banks to surround the railroad station and crush homes in its path left the town of 6,000 among the hardest hit in the area.

With Williamson’s businesses now reopened and the post-disaster sense of urgency gone, it’s tempting to think that, for residents of the Tug River Valley, the devastation of last spring has been reduced to a memory on a postcard rack. But inside the hundreds of HUD trailers which dot the narrow valley on the West Virginia-Kentucky border, it’s clear that the lives of flood victims have not returned to normal. And the pattern of corporate and government neglect — which added to the severity of the flooding and made disaster recovery even more tortuous — is continuing.

Through the media and their own organization, the flood victims’ protests have reached Washington — where several agencies are now preoccupied with evaluating their public relations during relief operations — and the West Virginia state capitol in Charleston, where Governor John D. (Jay) Rockefeller, IV, finally announced that he was tired of the victims’ “whimpering.” To date, no government agency has yet demonstrated a willingness to provide adequate flood protection for the Tug River Valley, or to tackle the underlying problems of how land practices like strip mining contribute to the severity of flooding by denuding the hills and clogging the rivers with sediment.

I’ve seen water back up that creek every year, all my life, but nothing like this. It was like a tidal wave. It tore things up just as far as it went. —Flood victim

No one was prepared for the fury with which the Tug River left its banks the night of April 4th. Sylvia Walker, her husband, Bud, and sixteen-year-old son, Terry, scrambled out of their house in Chattaroy Hollow, a few miles outside Williamson, and headed up the side of the mountain to escape the swollen creek. They watched while their house and the neighbors’ houses were demolished.

The scene was the same up and down the river. When the water receded the following day, homes that represented a lifetime of savings and work were badly damaged or totally destroyed, and priceless family pictures and personal possessions were washed downstream. Numbed flood victims crowded into churches, schools, or the homes of friends, set up tents on the hillsides, or lived in their cars.

After years of paying rent, the Walkers had finally managed to buy a small lot and house two years ago, and had spent countless hours making it their pride and joy.

“Other people say, ‘Well, my God, it’s just a house,’ ’’ said Mrs. Walker a few weeks later. “Yes, but you put everything you have into that house, your very souls almost, and it’s you — it’s you and your family — that have worked and loved and quarreled and done without to get to that particular spot.”

If you could ever get these federal people and state people to give you a straight and honest answer — regardless of what it is — then people might be able to plan a little bit. —Flood victim

The first wave of disaster relief was marked by confusion. The Red Cross, National Guard and state police were the first on the scene and their jurisdiction and chain of command was unclear. The state was ill-prepared to cope with such a disaster. Its 1971 emergency plan was outdated and virtually useless. An emergency operating center, hastily assembled in the basement of the state capitol building, suffered from lack of information and coordination. “It was just a circus,” recalls one of the state workers. It was not until several days later, when Governor Rockefeller put the newly named head of the state police, a former Army general, in charge of relief operations, that the state response assumed any semblance of organization.

The Federal Disaster Assistance Administration (FDAA) appeared a week later, after the county had been officially declared a federal disaster area. The agency’s “one-stop” centers were designed to help flood victims through the maze of federal programs available to them, but were staffed by workers hastily drafted for the job and not sufficiently trained in the complexities of federal relief programs; they offered a kind of hit-or-miss help and often left flood victims with unanswered questions after hours of standing in line.

The available answers were often disappointing. Despite the variety of federal help at hand, some flood victims inevitably fell between the bureaucratic cracks. For people whose homes were too damaged to qualify for HUD’s mini-repair program, but whose incomes made them ineligible for loans from the Small Business Administration, there was little help. Neither the mini-repair grant nor a special $5,000 grant to replace possessions offered under FDAA could be used to offset the SBA loan. SBA at first would provide loans only at its regular 6.625 percent interest rate; it took weeks of agitating by flood victims and Congressional action before loan rates were lowered.

One of the earliest and most effective disaster response mechanisms came from the citizens themselves. The Tug Valley Recovery Center (TVRC) formed a few days after the flood, and with the involvement of dozens of residents — flood victims, community workers, business people and others — set up shop in a local church and began feeding, clothing, sheltering and providing cleaning supplies to disaster victims. Hundreds of persons came into the church daily, and many became involved in the more political aspects of the TVRC: circulating antistrip mine petitions, organizing a daylong work stoppage to protest high SBA loan rates, demanding input into HUD’s activities and decision-making, outlining long-term land and housing strategies, leaning on the state to provide more effective response to the needs of the flood victims.

In the months following the flood, the all-volunteer TVRC remained the sole organized voice for flood victims. With support from various churches, it continued to sponsor social service projects and a home-rebuilding program using outside volunteer labor. The group remains a thorn in the state’s side on the issues of land and housing. A weekly newspaper published by the TVRC highlights the ongoing problems of flood victims and has strong community support.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) came in for the sharpest criticism from flood victims. To them, the agency’s mission of providing emergency and then temporary housing seemed mismanaged and inefficient.

HUD blamed its difficulties on the magnitude of the disaster (the largest since Hurricane Agnes in 1972), the mountainous terrain, and the shortage of available contractors to haul and hook up mobile homes.

The recovery was to be done in two phases: 16-foot-long campers would provide emergency shelter, and then standard-size mobile homes would be available as temporary dwellings. Flood victims immediately resisted the notion of being crowded in camper parks miles from their land, and asked HUD to change its policy to allow campers on homeowners’ sites while houses were being repaired or rebuilt. HUD eventually agreed to the change, but it took weeks to implement — and hundreds of flood victims ended up packed into campers at three Mingo County sites.

Even that was a slow process: by the end of April, only forty-eight families out of an estimated 1,800 who needed housing were in the campers. Some of the homeless were still living in cars or tents.

For the Walkers, the weeks after the flood followed a pattern typical for many flood victims: a few nights in their car, some time at the home of relatives, then in a church. May found them in a camper park, huddled with hundreds of other families on a Williamson ballfield.

Sylvia Walker says her neighbors were in a state of shock. “Some of these people I’ve known all my life, and they’re just like strangers — just like a whole new person,” she said in early May. “I go to talking to them, and I’ll joke with them and everything, even hoping that making them a little bit mad will kind of jar them a little. I think that if they get mad enough at me they’ll say, ‘Hmmph, if she can do it I can do it.’” An overpowering smell of raw sewage and a blistering heat wave in June made conditions in the parks even worse, but flood victims coped. A few feet of white picket fence, two folding chairs, and a mud-covered barbecue grill marked the outside of the Walkers’ camper. It wasn’t much, but it was home.

Adding to flood victims’ frustration were miles of HUD disaster mobile homes which lined a four-lane highway near Williamson. Not enough contractors could be located to haul them, HUD said, and they sat there for weeks.

I got mad, so I called over to the HUD office and I raised all kinds of Cain. Finally this man came on the phone and said, “What’s wrong with your mobile home?” I said, “I have no idea — I don’t even know where it is. I don’t have one.” And he said, "I’ve got it down here on paper that there is one on your site.” I said, “Well, somebody has lied to you — or else that thing is so pretty it’s blinding me and I can’t see it.” — Flood victim

The Walkers’ drawn-out journey from camper park to their own mobile home followed a pattern of foul-ups familiar to flood victims. During the first attempt to deliver their trailer to the Chattaroy site, it was damaged beyond repair. A lack of available trailers caused another delay, HUD says, but when more mobiles came in, the Walkers still didn’t get one. It was only after two weeks of irate phone calls — and the intervention of the top man in the local HUD office — that the Walkers discovered their problem. After site inspection by a HUD field worker, their property had been erroneously rejected as inadequate for the trailer. It was early July before the mobile home was installed and hooked up properly.

For many families, arrival of the mobile homes meant little; it was weeks before utility hook-ups were completed and they could actually move in.

Those whose homes were being restored to livable conditions under HUD’s mini-repair programs, meanwhile, faced a different set of problems. Mini-repair work, done by HUD-hired contractors, was often slow and shoddy. Moreover, many HUD policies lacked logic and were administered differently by the regional offices in Pittsburgh (which has jurisdiction over West Virginia) and Atlanta (which governs Kentucky). For example, HUD insisted that since it was not winter, mini-repair could not be used to restore furnaces, although homeowners argued it was impossible to dry watersoaked houses without them. The only loophole to this policy provided for repair if a doctor certified its need for health reasons. But unequal application of the provision resulted in furnaces for only half a dozen West Virginians, while several hundred were restored in Kentucky.

HUD and its special disaster mechanism, FDAA, committed another major blunder by locating disaster offices several hours driving time away from the flooded areas, citing the lack of motels, restaurants and available rent-a-cars at the disaster site. The move created a chasm between flood victim and federal bureaucrat, and even between HUD field workers and their office-bound superiors. Nobody, it seemed, could get a straight answer on anything from decision-makers a hundred miles away. Mingo County Commissioner Gerald Chafin threatened at one point to have HUD’s top person in the state arrested in order to get him to a coordinating meeting with flood victims.

“HUD came in here with the idea of going their own way,” Chafin remembers. “There was no attempt on their part to have any coordination with local government.” When Chafin found HUD workers wandering around lost in unfamiliar territory the first few days after the flood, he offered to provide county-paid local guides. He says it took HUD three days to come up with an official “yes.”

As the chorus of criticism from flood victims and the press swelled, HUD seemed to get even more uptight and inflexible. The agency’s concern with its image, in the eyes of many observers, interfered with its relief mission. One HUD field worker — who was yanked out of the area after making some candid comments at a community meeting about the agency’s inefficency — said, “Being in the Charleston office, HUD officials had no immediacy of the flood around them. But they did have print media and TV, and all they heard was bad PR.”

From the start, criticism of the relief effort was felt in official Washington — and resulted in a series of farcical encounters between flood victims and bureaucrats. In the first instance, a staff member from the White House Office of Public Liaison called to express what she termed “Administration concern.” She offered to help set up a meeting between officials and flood victims, but her offer of help was quickly retracted by her White House superiors. The call, they said, had not been officially authorized. Publicity in Washington prompted a visit from HUD Secretary Patricia Harris and President Carter’s son, Chip. A defensive Harris said the agency’s problem was its failure to communicate, and that HUD was doing the best it could. A visit a few days later from HUD Assistant Secretary Monsignor Geno Baroni seemed full of promise, but resulted in no action.

People’s whole lives were washed down that river, not just their homes. And nobody’s gonna do a damn thing for them. As long as that coal rolls out of here, they’re not gonna do anything. — Flood victim

The first, awful days are finally over.

But for the scores of families sitting in mobile homes on the flood plain, the lingering questions — about land, permanent housing and flood prevention — are of mounting concern. Mingo County, like the rest of southern West Virginia, faced a critical housing shortage before the flood, a situation aggravated by existing substandard housing and a growing need for units in the wake of the recent coal boom. With an estimated 1,400 families in the county affected by the flood, Mingo alone has a need for between 5,000 and 6,000 units immediately.

One solution is to build new homes for flood victims on land which is high, dry — and corporately owned. In its first official recognition of the dilemma posed by widespread outside corporate ownership of land, the state of West Virginia pledged in May to negotiate with coal and landholding companies for land for the homeless. The state legislature provided $10 million to buy the acreage. But after six months of negotiation, the state has come up with only thirty acres of land and an option to buy 270 more; it says it will be two years before the first site will be ready for house construction.

On December 1, Governor Rockefeller also announced that within twenty years the state expects to buy a 5,500-acre tract owned by the Philadelphia-based Cotiga Development Company — after the site has been strip mined by the “mountaintop removal” method which shears the tops off hills to get to the underlying seams of coal.

The Governor called mountaintop removal, “practically the only solution available to us for freeing up safe, flood-free land.”

The Tug Valley Recovery Center disagreed, charging that once again corporate interests were taking priority over people’s needs. The site to be stripped had been pinpointed all along by Valley residents as the most desirable housing acreage in the county — without being flattened by stripping. The plan to strip it “is proof beyond a shadow of a doubt that Rockefeller belongs to the energy interests and not to the people of West Virginia,” said TVRC spokesperson Jerry Hildebrand.

The TVRC also pointed out a discrepancy between the assessed value of the land under option and the price the state plans to pay. For example, a 120-acre tract owned by Cotiga has an assessed valuation on the county’s tax books of as little as $50 per acre for both surface and mineral ownership, but the state will pay a price “not to exceed $4,500 an acre” for the surface rights alone. (Cotiga will retain the mineral rights, although under the agreement with the state, the company won’t be permitted to continue to mine.) “If the land is worth $4,500 an acre,” said Hildebrand, “Cotiga’s holdings in the county should be reassessed and the taxes upped accordingly.”

The state’s plan thus far calls for providing housing starting at $30,000 — more than most flood victims can afford. Moreover, there are no firm plans to turn developed land over to flood victims who want to build their own homes. Nor has the state made any commitment to try innovative housing, such as pole-beam construction, which is adaptable to hillsides. The TVRC hopes to finish construction this winter on a pole-beam demonstration house built for less than $20,000.

The nearly 750 families whose rent-free year in HUD mobile homes expires in the spring face grim alternatives. They can buy their trailers, but according to HUD policy, they have to get them out of the flood plain. With eighty percent of the county’s acreage owned by outside corporations such as Georgia- Pacific, Island Creek Coal and US Steel, there is no land available to buy, and the state has made no moves to acquire the existing mobile home parks to ensure residents a place to stay. Or the flood victims can build on their own land on the flood plain — with no more protection than they had last April.

The Walkers are among the families caught in this bind.

“We’re looking forward to building a new home,” Sylvia Walker said in November, “wherever the state provides some land for people.” They have lined up a house loan, but the waiting continues.

“I think if the state wanted a new highway, or wanted to encourage a town to put in a shopping center, it would be done in no time,” she added. “It’s just like they don’t give a damn about the flooding victims. They’ll give it to us when they get good and ready.”

With no firm promise of land in sight, they plan to buy their HUD mobile home at the end of their rent-free year. Meanwhile, they fight the feeling of “temporary.”

“We’ve spent a lot of money in this trailer, trying to make it as much like home as possible. But you still go around with this feeling of temporary all the time. No matter how hard you try to make it have that feeling of permanency, you can’t do it. It sort of keeps you in a strain. I’ve had that feeling of permanency before, and I know how important it is and how good you can feel with it.”

We didn’t ask for much. We asked for 100 feet by 100 feet. We wanted to build a comfortable home, have a small yard, and just a small place to garden, if it’s just a tomato patch. You put us in a shoebox and we’re not going to be able to do anything. — Flood victim

Residents of one community upstream from Williamson found some available land and a coal company to sell it — and have given up on the state after it failed to help them obtain it.

“So far the state has promised us everything and refused to do anything,” said Wally Van Hoose, a young coal miner who has led the housing fight in the little community of Rawl.

Wally and Shelley Van Hoose and their two children had lived in their “dream house” only five months when the flood hit. It was destroyed. They moved in with relatives — three families in a house — and waited for a HUD trailer. The disaster had also taken away their livelihood: the mine where Van Hoose worked as a general laborer was flooded and shut down for two months.

By June, HUD had still not delivered a trailer. Desperate to move out of their crowded living quarters, the Van Hooses used a $5,000 FDAA grant and some income tax return money to buy a mobile home and put it on their house lot. Van Hoose was back at work just a few weeks when miners throughout the state went on strike to protest medical care cutbacks. The strike lasted ten weeks. With no income and no way to make payments on the house which had washed away, the family declared bankruptcy. Their 75-foot by 95-foot lot went back to the bank — which offered to sell it back to them for $5,000. With their mobile home now on bank-owned property, the Van Hooses could be given a 30-day eviction notice at any time.

A few weeks after the flood, Van Hoose approached his employer, Princess Coal, about leasing or selling some of their land on higher ground near Rawl. The company had turned down similar requests in the past, but was now willing to talk about selling land to the state which could then be developed for flood victims.

The idea mushroomed, and soon Van Hoose and his neighbors at Rawl had formed a small organization and were planning to relocate families in a hollow off the flood plain just a half mile away. Residents would help one another build homes. The state encouraged the plan, offering an architect to do layout and promising to put in water, sewage and roads. But nothing was done.

It was late December before the state proposed a plan for Rawl. The state would build six $30,000 houses and two dozen rental cluster units and sell them to the residents.

Van Hoose and the others were disgusted. “They’re going to bunch us together like sardines,’’ he complained. “When they get through, you could reach out and touch your neighbor’s house.” The group was also upset because the state proposal involved relocating two cemeteries.

Pointing out that the state had completely ignored their wishes to build their own homes on state-developed land, Rawl residents flatly rejected the proposal. The state agreed to scrap the plan, and the flood victims found themselves back where they were eight months earlier.

Van Hoose says many of his neighbors have given up on the state, and now plan to buy double-wide mobile homes or to rebuild on their old lots in the flood plain. He and some other neighbors however, have discussed the possibility of bypassing the state and negotiating privately with Princess Coal for the land. It would be far more expensive for the residents. “But if the state does it, you don’t have no say-so in what they’re doing,” said Van Hoose. “You take what they offer, and if you don’t like it, you stay here and get flooded.”

Back to normal? God, no. I hope nobody ever thinks that. As long as most of these people live in HUD trailers, it’s just gonna be a constant reminder to them of why they’re in that trailer in the first place. Seems to me like so many people think that as long as the businesses are going top notch, everything’s all right. Well, they’re wrong. —Flood victim

Eight months after the flood, Sylvia Walker finds that the numbness she described in the weeks following the disaster has worn off, but not the feeling of insecurity.

“You just feel like you’ve been thrown right out there in space and you’re sort of suspended — and nowhere to go but just stay right there. And those people who aren’t able to get out, or haven’t realized what they could do to fight this feeling, they’re in trouble. They sort of walk around like they’ve been given a tranquilizer.

“I think sometimes the only way people can hold it together is stay busy — at least for me that’s the answer.” She has thrown herself into her work as a VISTA volunteer for theTug Valley Recovery Center’s social services program — a job she likes better than her previous work as a grocery store clerk. “If I was back there, I’d just dwell on what has happened, and 1 don’t want to do that. The past has been quite rugged, and I really don’t want to think about it any more than I have to.”

For Sylvia Walker, Wally Van Hoose, and hundreds of other flood victims, the real tragedy of April may prove to be not so much the tangible losses as the intangible effect on their own mental health and their network of relationships with family and community. Mrs. Walker thinks the only way to deal with that threat is to fight back.

“Too long the politicians have done things their way,” she said. “I’m tired of being a puppet. I don’t intend to be nobody’s puppet no more. Once people understand they don’t have to be, they won’t. It’s just that simple.”

Tags

Deborah M. Baker

Deborah M. Baker is a free-lance journalist. Her research into the state and federal government response to the floods in Appalachia has been partially supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism in Washington, DC. (1978)