This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 2, "Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

When I began my work in the Delta in 1967, I was told that it was “past strange” for a white Mississippian like myself to record blacks in their homes. I found it impossible to work with both whites and blacks in the same community, for the confidence and cooperation of each was based on their feeling that I was “with them” in my convictions about racial taboos of Delta society. When whites introduced me to blues singers, our discussions were limited to non-controversial topics since performers felt my tapes would be played before whites in the community. In fact, local whites who provided contacts were suspicious of my work and often asked to hear the tapes.1

One introduction marked the last time I approached blacks through local whites. A white farmer agreed to let me record a blues player who worked for him and told me I should come to the performer’s home that evening. I arrived to find the farmer and several other whites in the yard adbniring a rifle; they all had guns hanging from rear window racks in their pickup trucks. When the farmer saw me, he called the player by throwing rocks on the tin roof. The singer came out and sang several songs on his front porch while the whites watched him from their trucks. He then complained his finger was too cramped to play anymore, and when the whites left I made an appointment to meet him again. The following night, the musician played at length and toward the end of the recording session he became intoxicated, cursed his white boss, and told me that he really owned the farm where he worked. He said the next time I came to town I should eat and sleep at his home and swore I would be safe with his family:

Next time you come, come on to my house and walk right in. If I eat a piece of bread, you eat too. I’m the boss of that whole place over there. I don’t know how many acres it is. You ain’t got to ask none of these white folks about coming to my house. Anytime you come to my house and I ain’t there, stay right there till I come. Don’t leave. I’m coming back, cause I’m going to git some pussy and I’ll be back in a minute. Any time you want to come down here, you drive to my damn house. Ain’t a damn soulgonner fuck with you, white or black.2

After this incident I approached blacks directly and found that as long as I remained in their section of town 1 could work freely and effectively without interference from local whites.3 When local police stopped and questioned me, I showed my Mississippi identification and was never arrested.

There were always exceptions to the patterns of segregation which stood out. While I interviewed Arthur Lee Williams, a harmonica player near Birdie, his white neighbor’s children arrived for dinner. Williams explained that his children ate their supper with the white family, and on weekends they sometimes picnicked and fished together.

I usually recorded in black neighborhoods of small towns, and my experiences in Leland, Mississippi, suggest the pattern of my field work. I found a black cafe and asked an older man if there were any blues singers in the area. He replied, “Well, you might talk to Son Thomas. His real name is James Thomas, but he go by ‘Son’ or ‘Cairo.’” Nicknames are given by the com- munity, and those of blues singers usually related to their music.

Nicknames such as “Pine Top,” “Cairo,” and “Poppa Jazz” are more important than surnames and often when I inquired after actual names no one recognized the person. I searched for William and Iola Jones for half a day before someone recognized them as “Jug Head” and “Don’t Know No Better.” The latter name was given because of Iola’s strange walk, and their friend “Night Duck” was so named “cause he do more traveling at night than in the day. He go anywhere and don’t be scared of nothing.”

I found “Son” Thomas’ home in a neighborhood known as Black Dog and asked his wife, Christine, if he was in. She said no one named James Thomas lived there, and asked why I wanted him. When I explained I was writing a book on the blues and wanted to include him in it, she admitted she was his wife and told me how I could find him.

I soon found Thomas and our friendship deepened throughout the summer. A good measure of our rapport was the response of his children, who were always more direct than their parents in showing their feelings toward me. When I first entered their home, they avoided me and rarely spoke in my presence. Later after I had spent many hours with their father, the children would run to the door and, holding my hands, lead me into their home, telling jokes and stories they wanted to record. It was some time after our first meeting that Son sang blues with strong racial themes such as “Smoky Mountain Blues.”

God forgive a black man most anything he do.

God forgive a black man most anything he do.

Now I’m dark-complexioned, looks like he’d forgive me too.

As children showed their trust through physical touch, my deepening relationship with Son and his friends was reflected in their recordings of stories and songs which increasingly used protest and obscenity. After we became close friends, he recorded verses like:

Well, it’s two, two more places, Baby, where I want to go,

Baby, that’s tween your legs and out your back door.

Well when I marry, now I ain’t gonner buy no broom,

She got hair on her belly gonner sweep my kitchen, my dining room.

I say belly, belly to belly, and skin, skin to skin.

Well it’s two things working and ain’t but one going in.

Well I asked her for her titty, or gimme her loving tongue.

She said “Suck this, daddy, till the goodie come. ”

Expression of affection through physical touch was characteristic of the black community. Son took me to Kent’s Alley and the home of his friend Shelby “Poppa Jazz” Brown who ran a blues joint for over 30 years. We shook hands and afterwards Gussie Tobe, a friend of Poppa Jazz, asked me, “Do you know what you just shook?”

“No. What?”

“A handful of love.”

This warmth and verbal banter was repeated whenever Tobe came to Poppa Jazz’s home. Poppa Jazz was 64, and when he spoke, he walked around the room dramatically gesturing and making boasts and threats before his seated audience. Once Tobe turned to me and said, “I want you to whip Jazz’s ass for me. If you don’t, I’m gonner go home for my shotgun and shoot the son of a bitch dead.”

Poppa Jazz turned to me and said, “I’m waiting for him. I’m waiting for him.”

He stood shirtless and walked around with his chest pushed forward. Tobe whispered loudly to me, “You wouldn’t think that man’s 80 and can walk around sometime without his cane.”

Poppa Jazz answered, “Watch your mouth cause I’m your daddy, Boy. I’m your daddy.”

Son then mentioned he had to dig a grave the next day for the white funeral home where he worked, and Shelby replied, “Another rich one gone. Boy, you gonner have plenty of money. Lend me a dollar.”

Poppa Jazz was living with a woman he had married 30 years earlier who had just returned after a 20-year separation. While I was in their home, a local woman who had “stayed with” Poppa Jazz for seven years dropped by and seemed surprised to see his wife there. The visitor asked Mrs. Brown a number of questions about her relation with Poppa Jazz, and when she left, Mrs. Brown turned to me and said, “I told her quick who was running this house. She must have thought I was just a whore he picked up.”

Mrs. Brown later told me of her experiences with the civil-rights movement and how she organized voter registration in her home town. Because of her bravery, she was selected to participate in the March on Washington in 1963 and described her experiences in detail.

Poppa Jazz saw that I listened to his wife sympathetically and began to tell me of the injustices he had known as a young man in Leland. He said blacks were considered “crazy” when they retaliated against a white. He left the South as a young man and lived in Northern cities because he was too proud to accept white intimidation.

He recalled one incident during his youth when he bought peanuts from a white man:

I wasn’t nothing but a little boy then. That was in 1912 and I wasn’t but 11 years old. They had this place that cooked peanuts outside, and you could smell them all over the town. I didn’t have but one nickle that day and I told my friend, I said, “Man, I want some peanuts, and I’m scared to go over here to get them cause this man, when he sell you the peanuts, he kicks you. ”

My friend said, “Man, look. Go and give him the nickel. Get them peanuts and when you hand him the nickle, don’t take your eye off him. When he raise his foot to kick you, grab it and that’ll trip him. His head’ll hit that concrete and you got it made. ”

So sure nuff I went on and give the man a nickle for the peanuts. When he aimed to kick me with his foot, I grabbed it, and his head hit the concrete. His momma was setting near him in a big chair, and she says, “The nigger killed my boy. Done killed my boy. ”

Then all the white folks grabbed me. They put a gun on me and whipped me cause I did that. That night I walked that railroad all night with a Winchester, but I didn’t see nothing. If I had of seen anything white like a chicken it would of been too bad. After that they called me the “Shotgun Kid.”

Poppa Jazz tells another story of an old black man who killed the sheriff in Leland:

He was an old man and didn’t live in no house. He stayed out in the woods, and he would come and get his hair cut in town. So one time he come to get his hair cut, and he went in there with a shotgun. Always carried a shotgun everywhere he’d go. He stood the shotgun in the comer to git him a hair trim and a shave, and when he got out of the chair to look for his shotgun, it was gone. He said, “Somebody done got my gun. ”

So they give it to him and he hit the railroad going back to where he stayed at in the woods. When the sheriff heard about him and the shotgun he went out there to get him, and the old man killed him. I was grazing my cows in that pasture and saw it with my eyes. Didn’t nobody tell me nothing. I saw it.

When they finally got the old man, they put him in a box and carried him up there in front of the pool room. They put four cross ties on top of the box and poured five gallons of gasoline over it. When they started the fire, it blowed up and the old man come out of there running. He run right here to the hotel, and they got him again and put a rope around his neck and hung him where the red light is right now. The first red light in town. When they hung him there, I was on the railroad looking. They said, “Boys, get off the railroad. ”

I didn’t go nowhere. I stood there looking. All my brothers and sisters was looking at him too, those what was big enough to see it. I left here after I saw all that stuff cause I didn’t want them to kill me. I figured next time it was gonner be me. They didn’t like me cause I’d fight. I’d kill anybody, white or black.

Poppa Jazz concluded, “In those days it was ‘Kill a mule, buy another. Kill a nigger, hire another.’ They had to have a license to kill everything but a nigger. We was always in season.”

Poppa Jazz’s home was a familiar part of the Leland blues community. His four-room house stood on Kent’s Alley between Fifth and Sixth Streets. Set between “old” and “new” Highway 61, it was the heart of what James Thomas calls “the rough part of town.”

During the day, visitors moved in and out of the home buying corn whiskey and asking which musicians would play that evening. Those who stayed to talk and tell stories sat with Poppa Jazz in the front bedroom which faced Kent’s Alley and gave Jazz a full view of activities outside. Often Jazz would tell a story, then rush to a window to check the alley, declaring, “No bullshit. I ain’t lying either. I ain’t lying.”

When night came, activity shifted to the back of the home as singers and dancers gathered in his blues room. The room was dimly lit, and there were no lights in the adjacent room where corn whiskey was chilled in a refrigerator. Poppa Jazz usually stood in the door between the two rooms and personally led customers to the refrigerator when they needed a drink.

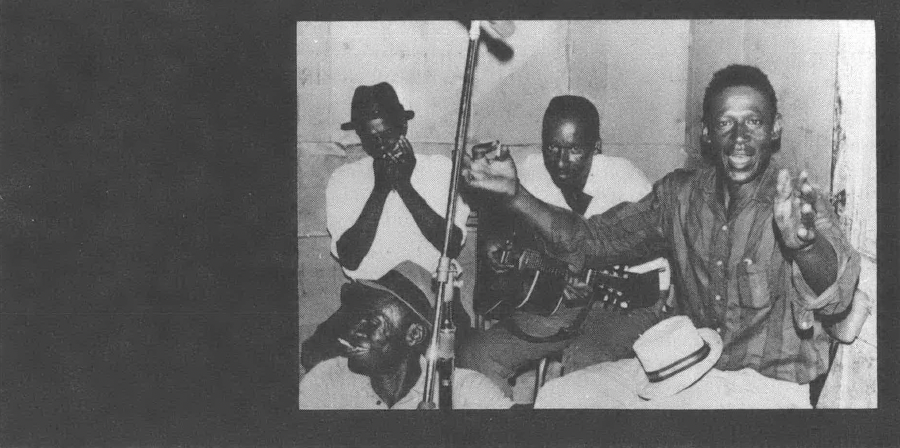

His main guitarist, James Thomas, played in a back corner beneath a calendar with a color picture of Jesus and his disciples. “Little Son” Jefferson sat on Thomas’ right and accompanied him on the harmonica. When asked how long they would play, Thomas replied, “Till late hours of midnight.”

Guests sat around the room on chairs and a large couch or danced in its center. James Thomas was the main attraction, and as the evening progressed, the audience became more responsive to his music. Women would answer his blues line, “You don’t love me, Baby” with “Yes I do, Daddy.”

Poppa Jazz moved constantly, serving whiskey, talking to visitors in the blues room, and leaning out its side door to encourage groups in the parking lot to come in. Occasionally he danced alone or performed a toast in front of Thomas, then resumed selling whiskey. Jazz knew his customers well, and those prone to fighting were closely watched and asked to leave if they became too loud. After escorting a man out the door he turned to me and said, “That was a bad one. They tell me a woman shot his nuts off in Chicago.”

Bluesmen like Arthur “Poppa Neil” O’Neil, Joe Cooper, and Eddie Quesie might play while Thomas rested, but they never replaced him as the main performer. When a third singer arrived, he would sit on Thomas’ left and wait for a break in the music. Gussie Tobe sometimes sat in the third chair and sang his composition, “The Ohio River Bridge.”

It was early one morning, when the bridge come tumbling down.

I say, it was early one morning when that bridge come tumbling down.

Well that Ohio River Bridge was tumbling down.

I told Cairo [ Thomas], oooh, when the bridge was tumbling down.

I was out there that morning when that bridge come tumbling down.

On that Monday morning, Baby, even that Wednesday morning, too.

We was working out there, I told the man in his office,

I said, “Look here, Mr. Mare, ” I said, The bridge is tumbling down. ”

Say, you know where I was at? Leeland, Mississippi.

Down here at Jazz’s place. Yeah!4

In the midst of this scene, the blues community grew like a family with a kinship of love for music and good times shared together. Until his death in 1974, Poppa Jazz was the central figure who held the Leland family together. As his name suggests, he became a father to aspiring singers like James Thomas, who was raised by grandparents in Eden. Thomas remembers how he first came to Leland on Saturday nights to visit his mother and sister.

James Thomas: On Saturday nights, that would usually be the night that I’d come to Leland. I’d get off the bus and go and see my mother and sister there. Then I would go round to Shelby’s club and he’d have boys around there playing the guitar. I’d go around and play some with them and then come back to the house.

Shelby was a big man then. He had plenty of money. He’d hold his head way high then and talk loud. He’d have men hanging around there playing the guitar and everybody’d meet up there on Sunday for big jokes and drinking. They’d have a nice time round there.

Poppa Jazz: That’s true. Yeah, that’s true. He ain’t joking none. When I’d see Son coming I’d be glad. It was just like that all night long. You know, we didn’t go to bed. Them there gals hung around me, you know, with that good liquor and stuff. They liked that. I started a jazz band and they started to calling me “Poppa Jazz. ” Well James, he come here. I knowed his mother and sister and all of them here, you know. And he came here one night. I had a joint open down there called the “Rum Boogie. ” He said, “I’m gonner play a number. ”

“What’s your name ?”

“James. ”

I said, “Go on. I know you. ”

I knowed who he was. So he went on that stage and everybody liked him. I said, “Buddy, when you come back through here, you stop. ”

So every time Son would come, he’d come over here and look for my guitar. He could play it. I’d be looking for him, too. That was when I named him “Cairo. ” You see at Cairo the water got so high, and he played that blues:

I would go to Cairo, but the water too high for me.

The girl I love, she got washed away.

He really rapped it. Everybody liked it. Everytime folks see me, “Hey, Man, you seen Cairo?”

“No, but he’ll be here tonight. ”

“We’ll be back then. ”

They sure did come. They liked to hear him play, and he could play all them kind of blues. I loved the blues all my life. That’s all I ever like. And I ain’t but 41.

James Thomas: Little Son Jefferson and me, we would sing our theme song to welcome everybody to Jazz’s place. We called him “Mr. Shelby. ”

Good evening, Everybody.

Peoples, tell me how do you do.

Well, we just come out this evening,

Just make a welcome with you.

Well it’s all on the counter.

People, it’s all on the shelf.

Well if you don’t find it at Mr. Shelby’s place,

People you can’t find it nowhere else.

Then when we got ready to close down the place we would sing:

Good bye, Everybody.

You know we got to go.

Good bye, Everybody.

People, you know we got to go.

But if you come back to Mr. Shelby’s place,

You will see the same old show.

Footnotes

1. Problems of “social etiquette” are discussed by Bertram W. Doyle in The Etiquette of Race Relations in the South (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1937)[Reprinted by Schocken Books, New York, 1971], pp. xviii - xix.

2. Anonymous Speaker. Earlier Mississippi studies which encountered similar racial problems are: Newbell Niles Puckett, The Magic and Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro (New York: Dover Publications, 1968), p. xxiii; John Dollard, Caste and Class in a Southern Town (N.Y.: Doubleday, 1949), pp. 32 - 40; Samuel C. Adams, Jr., “Changing Negro Life in the Delta” (Nashville: M.A. Thesis, Fisk Univ., 1947), pp. 5 - 6; and Allison Davis, Burleigh B. Gardner, and Mary R. Gardner, Deep South (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1965), pp. 15 - 18.

3. The dynamics of working in black communities are discussed by Roger D. Abrahams, Deep Down in the Jungle (Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co., 1970), pp. 16 - 38; Elliot Liebow, Tally’s Corner (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1967), pp. 3 - 28; Ulf Hannerz, Soulside (N.Y.: Columbia Univ. Press, 1969), pp. 201 - 210; and James Mason Brewer, Worser Days and Better Times (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago, 1965), pp. 23 - 24.

4. Paul Oliver discusses other blues on Ohio River disasters in The Meaning of the Blues, pp. 268 - 69.

5. B.B. King compares the blues audience which gathered around the singers to a family: “Whenever I would sing and have these people gather around me like they did, then this seemed to me as a family. This is another thing that made the blues singer continue to go on because this is his way of crying out to people.” B.B. King, New Haven, Conn. 1974.

6. This blues may be based on Sonny , Boy Williamson’s “King Biscuit Blues,” which was broadcast on the radio each day from Helena, Arkansas. Big Joe Williams recorded a version on his Traditional Blues (Folkways FS 3820).

Tags

William Ferris

William Ferris teaches folklore and Afro-American studies at Yale University and is co-director of the Memphis-based Center for Southern Folklore. This article is adapted from his forthcoming book, Blues From the Delta, to be published by Doubleday in February. The photos here are by Ferris. (1977)