This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 4, "Generations: Women in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

— Billie Holiday

On May 3, 1930, a Sherman, Texas mob dragged George Hughes from a second floor cell and hanged him from a tree. Hughes was accused of raping his employer's wife. But the story told in the black community, and whispered in the white, was both chilling and familiar: an altercation over wages between a black laborer and a white farmer had erupted in ritual murder. The complicity of a moderate governor, the burning of the courthouse, reprisals against the black community — all brought the Sherman lynching unusual notoriety. But Hughes' death typified a long and deeply rooted tradition of extralegal racial violence.

Unlike other incidents in this bloody record, the Sherman lynching called forth a significant white response. In 1892, a black Memphis woman, Ida B. Wells Barnett, had initated a one-woman anti-lynching campaign; after 1910, the NAACP carried on the struggle. But the first sign of the impact of this black-led movement on Southern whites came in 1930 when a Texas suffragist named Jessie Daniel Ames, moved by the Hughes lynching, launched a white women's campaign against lynching. Over the next 14 years, members of the Atlanta-based Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching sought to curb mob murder by disassociating the image of the Southern lady from its connotations of female vulnerability and retaliatory violence. They declared:

"Lynching is an indefensible crime. Women dare no longer allow themselves to be the cloak behind which those bent upon persona! revenge and savagery commit acts of violence and lawlessness in the name of women. We repudiate this disgraceful claim for all time.”1

Unlike most suffrage leaders, Jessie Daniel Ames brought the skills and consciousness acquired in the women's movement to bear on the struggle for racial justice. The historic link between abolitionism and women's rights had been broken by the late nineteenth century, when an organized women's movement emerged in the former slave states. Ames herself had registered no dissent against co-workers who argued that woman suffrage would help ensure social control by the white middle class. But as the Ku Klux Klan rose to power in the 1920s, she saw her efforts to mobilize enfranchised women behind progressive reforms undercut by racism and by her constituency's refusal to recognize the plight of those doubly oppressed by sex and race. As she shifted from women's rights to the interracial movement, she sought to connect women's opposition to violence with their strivings toward autonomy and social efficacy. In this sense, she led a revolt against chivalry which was part of a long process of both sexual and racial emancipation.

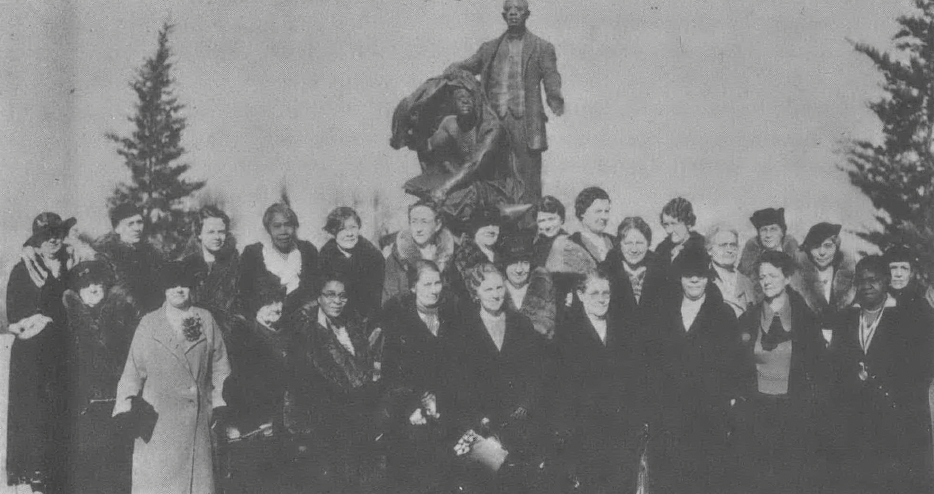

Two interlocking networks of organized women converged in the creation of the Anti-Lynching Association. From evangelical women's missionary societies, Ames drew the movement's language and assumptions. From such secular organizations as the League of Women Voters and the Joint Legislative Council, she acquired the campaign's pragmatic, issue-oriented style. Active, policy-making membership consisted at any one time of no more than 300 women. But the Association's claim to represent the viewpoint of the educated, middleclass white women of the South depended on the 109 women's groups which endorsed the anti-lynching campaign and on the 44,000 individuals who signed anti-lynching pledges.

Ames' commitment to grass-roots organizing, forged in the suffrage movement, found expression in the Association's central strategy: By "working through Baptist and Methodist missionary societies, organizations which go into the smallest communities when no other organizations will be found there," she hoped to reach the "wives and daughters of the men who lynched."2 Once won to the cause, rural church women could, in their role as moral guardians of the home and the community, act as a restraining force on male violence.

The social analysis of the Anti- Lynching Association began with its perception of the link between racial violence and attitudes toward women. Lynching was encouraged by the conviction that only such extreme sanctions stood between white women and the sexual agression of black men. This "Southern rape complex," the Association argued, had no basis in fact.3 On the contrary, white women were often exploited and defamed in order to obscure the economic greed and sexual transgressions of white men. Rape and rumors of rape served as a kind of folk pornography in the Bible Belt. As stories spread, the victim was described in minute and progressively embellished detail: a public fantasy which implied a group participation in the rape of the woman almost as cathartic as the lynching of the alleged attacker. Indeed, the fear of rape, like the fear of lynching, functioned to keep a subordinate group in a state of anxiety and fear; both were ritual enactments of everyday power relationships.

Beginning with a rejection of this spurious protection, Association leaders developed an increasingly sophisticated analysis of racial violence. At the annual meeting of 1934, the Association adopted a resolution which Jessie Daniel Ames regarded as a landmark in Association thought:

"We declare as our deliberate conclusion that the crime of lynching is a logical result in every community that pursues the policy of humiliation and degradation of a part of its citizenship because of accident of birth; that exploits and intimidates the weaker element ... for economic gain; that refuses equal educational opportunity to one portion of its children; that segregates arbitrarily a whole race.... and finally that denies a voice in the control of government to any fit and proper citizen because of race."

"The women," Ames proudly reported, "traced lynching directly to its roots in white supremacy."4

Although the Association maintained its single-issue focus on lynching, its participants also confronted the explosive issue of interracial sex. They glimpsed the ways in which guilt over miscegenation, fear of sexual inadequacy, and economic tensions were translated into covert hostility toward white women, sexual exploitation of black women, and murderous rage against black men. Their response was to demand a single standard of morality: only when white men ceased to believe that "white women are their property and so are Negro women," would the racial war in the South over access to women come to an end. Only then would lynching cease and social reconstruction begin.

By World War II, the anti-lynching movement had succeeded in focusing the attention of an outraged world on the most spectacular form of racial oppression. The black migration to the North, the emergence of an indigenous Southern liberalism, the interracial organizing drives of the CIO all contributed to the decline of extralegal violence. This successful struggle against terrorism made possible the emergence of the post-World War II civil-rights movement in the South. Only with the diffusion of massive repression, of overwhelming force, could the next phase of the black freedom movement begin: the direct-action assault on segregation in the Deep South. On February 21, 1972, Jessie Daniel Ames died in a hospital in Austin, Texas. The civil-rights movement had long since bypassed the limits of her generation's vision of interracial cooperation and orderly legal processes. Ames had not become part of the folklore of Southern struggle. But, with the rebirth of feminism from the crucible of the civil-rights movement, her career has come to be seen in a more favorable light.

On February 12, 1972, as Ames lay dying. Congresswoman Bella Abzug of New York addressed a Southern Women's Political Caucus in Nashville. Exhorting her audience to use the political power of organized women to affect the issues of the day, she could find no closer analogy for such a movement than the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. Jessie Daniel Ames would have wanted no better tribute.

FOOTNOTES

1. A New Public Opinion on Lynching: A Declaration and a Pledge, Bulletin No. 5, 1935.

2. Minutes, ASWPL, Jan. 13-14, 1936, ASWPL Papers, Atlanta University.

3. W. J. Cash, The Mind of the South (NY: Random House, 1941), pp. 116-20.

4. Norfolk (Va.) Journal & Guide, Jan. 20, 1934; Jessie Daniel Ames to Miss Doris Loraine, March 5, 1935, ASWPL Papers.

5. Minutes, op cit.

Tags

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall

Jacquelyn Hall, a guest editor for this issue of Southern Exposure, teaches history at the University of North Carolina and directs its Southern Oral History Program. She is currently finishing a book on women and the anti-lynching movement to be published by Columbia University Press. (1977)