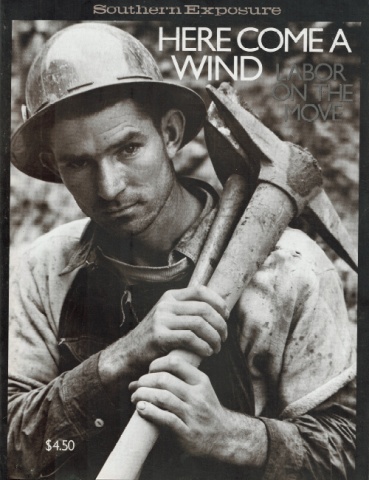

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Selina Burch was a 17-year-old switchboard operator in Dublin, Georgia, when she joined the Communications Workers of America (CWA). In a town with only one movie theater, going to a union meeting was a social event, a place to meet the young men who worked in the Western Electric plant. Instead of an antagonist, she viewed her employer as a benevolent parent - “Mother” Bell. Her first strike in 1947 was “like being out of school on vacation.”

By the mid-1950s, Selina had run against the male leadership for the presidency of her local in order to get it “into a position where we would not have to take any crap again. ” And she had gone through another strike where she was personally harrassed by Bell Telephone and accused of committing an unfair labor practice.

Today, Selina Burch has become a top official in CWA, an administrative assistant to one of the union’s 12 district vice presidents. She regularly pushes Southern Bell to the wall in negotiating sessions, demonstrating the skills that have brought her respect from employers, politicians and other union members. She has learned a great deal about power in the years since she first asked callers, “Number, please.” As a woman, a worker, and a union leader, she learned how power worked, how to get it, and how to use it for her members - and against her enemies.

As she tells new members, the union is like a choir, dependent on no one voice, but deriving its effect from a harmonic, collective force. She believes deeply in her union but also recognizes that her voice, representing the desires of the women and black members who support her, “has shaken up CWA from top to bottom.”

Teaching workers and settling their grievances has been her work; electoral politics, her hobby and avocation. She has, in fact, gained considerable fame as an expert coordinator of phonebank campaigning. After all, who knows better how to talk to a voter over the telephone than a telephone operator? She knows that a tightly organized union is a ready army to offer a candidate, and a politician’s friendship can be a tool for accomplishing personal and organizational goals.

Her most recent “friend” is Jimmy Carter, who sought her help in the Georgia and Florida primaries and, early on, asked her to be a Carter delegate at the Democratic convention. She accepted largely because she saw that, at the Democratic mini-convention in 1974, “Jimmy Carter just stood out head and shoulders above everyone else when it came to insisting that women ’s rights be written into the Democrat’s program.”

In the following interview, Selina Burch tells the story of her education as a labor leader and woman trade unionist; how, as she says, “the rebel in me came out.” It was conducted and edited by Sean Devereux, a former newspaper reporter in Florida and North Carolina and summer intern with the Institute for Southern Studies’ weekly newspaper column. “Facing South.”

I grew up in Dublin, Georgia. My father was a farmer and my mother was a homemaker. My mother died when I was 13, and I moved in with my grandmother and four old-maid aunts — three of them were schoolteachers. There was no labor background in my family at all.

I began work for Southern Bell on August 7, 1945, as an operator. I had graduated from Dublin High School and had worked in a coffee shop for about a year — there’s no labor market in Dublin, Georgia. After a year, I applied for a job with the telephone company. The chief operator had gone to school with my father, so I was put ahead of all the other applications.

In 1946, some people from Macon came to Dublin and signed us up to a union. If you were a female, you paid 75 cents a month to belong to a union, and if you were a male, you paid a dollar. I was an operator and was working eight to five every day, the best shift because of my family’s friendship with the chief operator. Suddenly, I was assigned to that horrible tour of one to ten. Someone had come along and taken my privileges away. I was young and carefree, though, 17, 18, and it really didn’t make any difference to me, that part of it.

You really became shockproof. I had been brought up in the Baptist Church where a child had to go to church twice on Sunday and once on Wednesday, Training Union and Sunday School and all that. Then, to have people that you had admired as a child, deacons that you thought were morally great people, suddenly asking you for dates on the telephone! Of course, they had no idea who they were talking to. I guess that was my first realization that the world was not made of cotton candy.

Also, right away in 1946, we obtained our first wage increase. At that time, I was making $15 a week as an operator and I got a $10 increase. It had a great impact on me that somebody had almost doubled my salary, but I did not understand at that time what it was all about. I had no idea what unionization meant. Pay, it meant more pay. But as for any other privileges, all it meant was that I went to the bottom of the list, because I was the junior person there.

At that time, remember, there was a manual board where you said, “number please.” There was no automatic dialing in Dublin. The manual board was what I learned on. If you’ve ever walked into a telephone company, you’ve seen all those cords being put up. It became a fascinating thing to me to see if I could put up all the cords, and then move over to another position, because I was very adept at handling telephone calls. There was one other girl in Dublin who could keep up with me, but only one. This was a challenge to me, to see how fast I could work the switchboard.

I remember the first union meeting I ever went to. Over in Macon. It was during a strike, and we wanted to see what we were striking for, but we didn’t find out. I’m not real sure that anyone in Macon knew.

The strike didn’t bother me because even though my family were schoolteachers, we had a car. I could borrow a quarter to buy a little gas, enough to get to Macon. There was only one movie in Dublin, so driving to Macon was something for us to do. The Western Electric guys were out on strike also. Everybody would get together at meetings and we’d laugh and talk about the strike, whatever it was about.

We were a close-knit group. I guess that we were friends more because we worked together all day than because we were members of the union. Dublin was a pretty small place. We all stayed together, except for two people. When we returned to work in ’47, I remember that we gave the two who had not come out on strike a pretty hard way to travel. I resented them.

It was like being out of school on vacation. In fact, the day we were supposed to return to work, I had a big date that night, what I considered at that time a big date. I called the chief operator and said that I couldn’t possibly come to work because I had such a sore throat.

We were so young and naive that we did not even think of picking up the telephone and making calls. You see, with only a manual board there, if we had been militant and had known what we were doing, we could have driven Mother Bell nuts. But we did not want to inconvenience her in any way. We thought we were a big inconvenience just being out on the street. It was part of this Southern upbringing: we respect authority at all costs.

And with Dublin so small, I didn’t think of “the company” as huge, nation-wide Bell Telephone Company. I thought of the company only as the people I worked with. My grandmother broke her hip during this time, and the chief operator called me at home - my grandmother’s home where I was still living — to assure me that she would make sure that any calls from our number went through, even though they were having trouble keeping up on the switchboard because of the strike.

II

I was married in 1948. My husband was in the Navy, stationed in Charleston, South Carolina, and I transferred there, still an operator. Charleston did not have a manual board; everything was automatic. It was a much larger office. It took time to get acquainted. I had never lived in a town that size before.

The union was much stronger because the local was right there in Charleston. You personally knew the local officers because they worked with you. The local president and vice president worked in the building with us. The secretary-treasurer of the local was a woman. This was the first time I had seen the union operate. What I remember is seeing meetings being held with management on grievances. With this closeness and knowing the people involved, you would hear the news as soon as the grievance meeting was over; who had won and who’d lost. I got a much better sense of what a union could do for its people.

After we had lived in Charleston for several years, I began to have marital problems. My husband was no longer in the Navy. Through this time, I began to turn more and more to the union for some way to occupy my time. I began to handbill for the local. In 1952, on a dare, I ran for local secretary-treasurer against five opponents and won. All of my opponents were women, because at that time in Charleston, you have to remember, the woman could only be secretary-treasurer. They let the males have the president and vice president — you know, be the spokesperson.

Anyway, I won on the first ballot. I had never even been to shop steward school, so I knew nothing about the technical parts of the contract — how to handle a grievance or any of that. I did know that we were not as well organized as we should have been. From the start, I enjoyed the battle of wits across the table from the company. I was always pushing to see how much I could win.

I was divorced by this time and giving all of my time to the union. I was very dedicated to seeing that we became the best local in South Carolina — having the most political contributions, the best settled grievances, being more active in the community. I saw what you could do, if you just made up your damn mind to do it.

It’s a thousand wonders that I didn’t get fired, that the people who followed me, that we all didn’t get fired. We would do stupid things like going into the company cafeteria and setting all the vacant chairs up on a table so, unless you had a union card, we wouldn’t let you sit at our table. I wasn’t angry with the non-union people, just determined that they would join. We laughed it off in the cafeteria, but we still wouldn’t let them sit there. The company threatened to fire us all, but we told them that if supervisors could save seats for their boyfriends, we could save a chair for any friend of ours. Except, (laughing) we were saving 20 chairs.

We came from a 55 percent local into a 92 percent, tightly organized local in short of nothing.

By this time, I was no longer an operator. I had been promoted to an “instructor.” The company had me teaching new people who came to work as operators. The job meant more money and it got me away from the board. But more than that, it gave me a direct advantage in organizing for the union. Two new people showed up every other Monday morning and, of course, they were eager to learn because they wanted to stay. If they didn’t join, they didn’t learn.

I didn’t come right out and say, “Look, I’m not going to teach you to be an operator if you don’t join the union.” But I would tell them about the union and tell them that I was an officer and what benefits there were. They’d have to take every break and lunch hour with me. New students always want to get along with whoever is teaching them. To them, I was the authority. So they joined the union.

There was only one girl that ever reported me to the company for my “tactics.” She told the chief operator that I had threatened her. I laughed and said, “Yeah, I carry a gun and a knife with me at all times. You believe that don’t you?” That ended that. The girl did not last.

I had learned one important thing about working for somebody: be better than everyone else. One thing that I always had going for me was that I was a producer. The company left me alone because of my ability to operate a switchboard, my ability to teach and my ability to get people to follow me. They had no gripes about my work. It has always been my belief that the best steward, or the best local officer, is the person who doesn’t have the grievances himself. That person can become a leader without having to submit to anything from the company. Because of my ability to work and my ability to lead, I didn’t have to ask the company for anything.

Also, for the first time in the history of the Charleston local, the company came to the officers of the local and wanted us to help them in the city United Fund Drive. We were able to select people who were the leaders in different departments and we collected more for the United Fund — Community Chest, they called it then — than had ever been collected in the history of Charleston.

I remember that we were having trouble finding a place for the CWA to meet, except in the Tobacco Workers’ Hall, which was down by the railroad tracks in pretty dangerous territory. Through working with the Community Chest, I met the man who ran the Jewish Community Center in Charleston. They offered us their hall, free of charge. It was funny, because later, during the ’55 strike, after I was gone, the Jewish Community Center became the CWA strike headquarters. They put pressure on the Center, saying they would cut off their Community Chest funds, but the guy at the Jewish Center just reminded them that CWA had collected a lot of that money. So the union kept on meeting at the Center.

III

I guess the rebel in me really began to come out somewhere between 1952 and ’54 when I saw that, or felt that, I was doing all the work and a male was getting all the credit. In 1954, I decided that I would run for local president.

There were no women local presidents in South Carolina, nor in Georgia then. The men in the local came to me and told me that I could remain secretary-treasurer of the local as long as I wanted. They promised always to vote for me for secretary-treasurer, but they said they would never vote for a woman for president.

I said, “I can count also, and I know that there are more women than men in this local so just come along to the election.” I won the thing hands down.

That was in the fall of ’54, when in this district which then covered nine states, there were three females on the CWA staff. Sometime earlier that year, the guy who was in charge of the nine Southeastern states, Bill Smallwood (he later became the International secretary-terasurer of the union) came to a state meeting in Columbia, S.C. I was the one presenting the local reports. I did not know it at the time, but later on I found out that when he heard me that night, he said to one of his people, “That’s my next staff person.”

In the early part of ’55 when I had been local president for a few months, one of the three females on CWA staff married some guy and left the union. I had built a well organized local. We had contributed money to PAC (the CIO political action committee) over and above union dues. Our local had a good record of settling grievances. So, I was offered the staff job.

I had never really thought about being on CWA staff. I was just trying to get the Charleston local into a position where we would not ever have to take any crap again, that we would be so well known in the community and so respected that no one would dare say anything to us.

I told the people at CWA headquarters in Atlanta that I didn’t know if a staff job was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life and that I would go home and think about it. You see how naive I was: people were dying for that job, people had worked a long long, time for a staff job and here I was, asking to think about it. It was an accident. I was in the right place at the right time, when a woman left the staff. I thought it over: I enjoyed teaching and teaching in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana was going to be my assignment. In about a week, I called them and said I would accept. I was 27, the youngest person ever on the CWA staff.

On March 14, 1955, CWA struck the company. I hadn’t even moved into my office in Jackson, Mississippi. I always laugh and say that CWA threw me into the fish pond to see if I would sink or swim. Instead of to Mississippi, I was sent to New Orleans to administer the CWA defense fund. When I arrived in New Orleans, I had with me a check for $25,000. All the strike funds were being set up in personal accounts, so the company would not find out how much we had and how much we were spending.

The strike went on for 72 days. In that time, I paid out $699,000 in the state of Louisiana for bread and beans and house payments and car payments. We did not give any money to strikers, but we would not let them lose a house or a car. We had 10 million little problems with the defense fund, like, maybe a local buying something that was not authorized under the defense fund rules of the international union. We’d have to refuse them and spend a great deal of time, explaining why to the local.

I was living in a hotel, not getting much sleep at all. It is terribly hot in New Orleans in March, April and May. I felt very grimy and dirty all the time. And it was still a male versus female thing. They assumed that women were more adept at doing the clerical work and taking all the garbage from the locals, so that is what I was doing.

But, also, I figured I’d come a long way from saying “number, please” in Dublin, Georgia, just three years before. Working in the strike was exciting to me. I learned that women could get by with more than the males. We could stir the scabs up and police would threaten us, but there was no violence. CWA had it set up where the women would picket from six a.m. to six p.m. and the men would take up the signs at six p.m. to six a.m. The scabs - a lot of them were Tulane students — would come out of the building on the hour and on the half-hour and the women, we were taking the signs at five minutes to the hour until five minutes after.

I decided that we needed some lively things to get the spirits of the strikers built up. We made up songs, like, “Oh, when the scabs come crawling out....Oh, Lord, I don’t want to be in that number, when the scabs come crawling out,” and “Old Ma Bell, she ain’t what she used to be...a couple of months ago.” We would sing with the police surrounding us. We told the police that we would not get involved with them in violence. One night we had a parade, 10,000 people in the parade. You could see the scabs peering out the windows. The street had been empty when they went to work. They must have been petrified looking out at 10,000 people. But, after the strike, we had only four people fired out of 5,000 members of the New Orleans local. That was because of these kids getting their emotions placed in pranks and singing instead of in violence.

The CWA workers in New Orleans were just looking for someone to lead them and once we got the morale up and the spirits up, there was no problem. You’ll find that people will strike over a principle sooner and longer than they will over money. We wanted maternity leave in the contract and we wanted the right to arbitrate any suspension and the right of any union member not to have to cross a bona fide picket line. Seventy-two days later we got those things.

There was bitterness left on both sides. After this ’55 strike, we had the biggest set of arbitration hearings that have ever been held between a company and a union in the history of the labor movement. Two hundred and forty-eight people were fired from Southern Bell alone. I think there were some 40 fired in Louisiana. There were four arbitrators after the strike and all four were put on a black list by Bell Telephone and not a one of them was ever used in any arbitration hearings again, anywhere in the Bell System. It wasn’t like the ’47 thing, when I was back in Dublin. There was a real split after the ’55 strike. The company and CWA were no longer one big happy family.

I felt the bitterness personally. I watched the company’s reaction to the strike. The company would send down supervisors every night to watch us, you know, and say nasty things to us. Their emotions were very high; they didn’t even like our singing and joking around. They didn’t think our people would last that long. The company had these movie cameras going. They had spotlights on me everywhere I would move in the crowd. They must have reels of movies of me. Of all the staff people in the nine Southeastern states, I was the only one accused of an unfair labor practice. The company charged me with not carrying a picket sign correctly, swinging it too fast, turning on my heel too fast. Nothing came of it, though, with the labor board.

CWA asked me to stay in Louisiana after the strike. We had a number of locals in Louisiana that thought they could do without a national union; they were fighting national and district headquarters all the time — Monroe, Shreveport, Lake Charles. The district vice president carved out those locals and said, “Here you are, Selina.” I had the central, northern and southwestern part of the state, but I had to live in New Orleans, because that’s where the company’s headquarters were. It was a big assignment. For example, the Monroe local had 32 counties in its jurisdiction. I had a title, “North Louisiana Director,” and I was going to set the woods on fire.

All the locals in the state had male presidents. There was a certain amount of resentment. No matter how well I did, they were always going to think, some of them, that a male could have done it better.

When I was hired, when I first agreed to come on staff, I’ll never forget, I was taken into a room by the assistant district director. He began to say to me...he was kind of a reserved guy and didn’t really know how to approach what he wanted to say. Finally, I caught his eye and I asked him right out, “Are you trying to tell me about the birds and the bees?” And he says, “Yes.” And I said, “I know all about the birds and the bees.”

He said to me, “But you, with your youth, you are going to be confronted with so many situations.” And I said, “No, I won’t. I know exactly how to handle it.”

He thought that I would be put in difficult situations because all the local presidents then were males, that I wouldn’t know exactly how to handle them. But I did.

I believe the old saying, “You don’t get your honey, where you make your money.” I had one basic thing that I required of a local president. The first time I met a local president, he had one of two options: he could take me home for dinner; or, he could bring his wife and family and we’d go out to dinner. I did not have a family of my own, but I knew something about families. I had learned that I had to build this type of relationship with the family. If you wanted a local president to really do a job, he had to have an understanding wife and a trusting wife. There were many nights when I was out with that local president until two and three in the morning. I built this type of relationship for myself and for the union. There was a great love and a great closeness between me and the wives of local presidents. I still get graduation invitations from children all over Louisiana.

IV

I had learned early enough that the one thing that made Mother talk was money and whoever controlled the purse strings would have the biggest influence with the company. In Louisiana, the Public Service Commission sets the pay telephone rates, and — what’s more important — the intrastate long distance rates. I decided that CWA should put an effort into electing friendly Public Service Commissioners. There were three commissioners, one on our side and one who voted most often for the company. The third man was from near New Orleans and he was not an enemy, but he was not what we considered a friend to CWA, either. That was the race we worked on, the swing vote commissioner’s election. After we had made a difference in the election of that commissioner, CWA came to have great influence with the Commission.

Well, it came about that the company was seeking a $20 million rate increase. Until that time, Public Service hearings where telephone rates were being considered were attended only by company officials. I got notice to all local presidents and officers in my territory, and we started going to Baton Rouge to attend every Commission hearing. This got the local officers close to the commissioners and it made the company realize that we were to be reckoned with.

So, the Commission voted: instead of a $20 million increase, the company got a $10 million decrease. The pay station reverted back to a nickel and is still a nickel today. The guy who was in charge of Southern Bell in Louisiana, the vice president, he was shipped back to Atlanta.

The company brought in a guy named Homer Bartee from Kentucky to be vice president. He came with a pretty bad reputation for being hard on the union. Of course, he was going to set the woods on fire, too. Right away, he refused to sit down with us and deal with our grievances.

CWA is neutral in most rate increase fights. But in Louisiana at this time, 200 union members had been laid off, because of the rate decrease. I decided to take a risk: the union was all for the increase, but I wouldn’t give a CWA endorsement, until the company came and asked me for it.

Bartee held an executive session and said that he’d never ask the goddam Communications Workers of America for a thing.

“Fine,” I told his people. “I hope him all the luck in the world with his rate increase.”

We sat through another rate hearing, and he lost it. The company was denied their intrastate long distance rate increase again. They decided that they would appeal to the Supreme Court.

I had an unlisted telephone number, but Bartee managed to find it. He wanted to know what I could do to help him. I told him I didn’t know, but we got permission to file a brief in the Supreme Court in support of the increase. The court upheld the Commission, but the CWA brief was the only one mentioned in the opinion when it came down. After that, there came to be a very good relationship between Bartee and myself.

So when emotions died down and I was able to sit down and talk with the company, CWA accomplished new things that could not have been accomplished without building that kind of relationship. My big problem was with the North Louisiana locals. I was learning that it all tied together — your relationship with the company and your relationship with the locals — but I had no idea in the beginning how it would work out. I was playing it one step at a time.. .praying.

The Monroe local was the worst. You have to remember that from Alexander north is the Bible Belt. In the early 1960’s all through that north section, everybody was calling everybody else a Communist. Chet Huntley, David Brinkley and Walter Cronkite were all suddenly Communists. There was an organization in North Louisiana - a sort of John Birch sort of group - that was taking up money for General Walker and trying to have Life and Look magazines banned as Communist. You couldn’t talk reason with people about integration at that time.

Down in New Orleans, I had involved CWA in several school board elections where integration was a problem. Some of the New Orleans school board members who were liberal were being accused of being Communists. I picked several contests where it meant something to the community and ran a CWA phone bank for the liberal candidate. I did it more for the children of CWA members than for any other reason. So the Monroe local knew where I stood. I had had a rough time at one of their meetings where I talked their members out of donating a thousand dollars to this crazy organization. To them, every liberal thinking person was a Communist.

One of the loudmouths in that local was a cable splicer who had been suspended for falsifying work reports. The local officers asked him if he wanted CWA to process a grievance in his behalf. He told them, hell, no, that he was going to work, union be damned.

Then, the company fired him. Now, he’s without a job at all, and the guy wants the union to help him. So the local tried to process the grievance, but they allowed the time limit to expire. Everybody in management all over the state was laughing up their sleeve. Here this guy had been fired and the Monroe local couldn’t even get the grievance in the mail on time. Everybody in the state knew about it. Even this crazy John Birch organization was trying to get involved in the thing. The local officers were all excited and didn’t know what to do. They were calling me by now.

I called the personnel guy for Southern Bell at Monroe and asked him to tear up the envelope that had the postmark on it and accept the grievance. He wouldn’t do it. He was having too big a time embarassing the local.

So, I called Bartee and asked him if he would take me to lunch. At that stage of the game, I had decided that I wanted this cable splicer reinstated with no loss of service. I didn’t just want the grievance reinstated, because if the union had arbitrated the grievance we could not have won it. The guy was guilty as sin. While Bartee and I were eating lunch, I told him what I wanted.

“Well, hell, no damn problem. Is that all you want?” he asked me.

I told him, “Before you give me a fast answer, Bartee, remember everybody in your company in Louisiana is laughing up their sleeve over this.”

He said, “I don’t give a damn. I’m the vice president of the company and I tell you that the man will go back to work next Monday morning.”

The company personnel man was very embarrassed by all this. He tried to fandango with me, trying to get me to accept something else, anything else in the whole state. Bartee had already told him to put the union man back to work, see, and it made the personnel executive look bad. I just said, “I haven’t asked you for anything. If that cable splicer’s not going back to work on Monday, just tell Homer Gray Bartee to call me.”

The man went back to work. That one thing brought the Monroe local back together, and brought them back into the international. I didn’t have any more trouble with them after that. In fact, at that time, the president of CWA said that if we had the type of relationship with the Public Service Commission in other states that we had in Louisiana, we would be very fortunate and not have to work so hard. I was riding high then. I was showing the world that I knew a thing or two.

V.

I did a lot of teaching. Organizing and teaching comes before politics. You’ve got to have members supporting you, before you can start involving the union in politics. I was forever going around from one little town to the other, spending the day with the local president, making sure that he knew the members in his town, that he knew their problems, that everybody had a job steward. I had to be sure in my own mind that their job stewards were the caliber of people that would be leading them and not someone that was using the union to better himself first, just looking for the prestige, because there is a lot of prestige in being a job steward.

Politics was something else beyond organizing, but it all ties together. You had to give the members something that they could be proud of and wanted to hang on to. You see, for most of the members there’s only one thing the union does: handle their grievances. That’s the most visible thing. It was hard at first to get union members involved in the Public Service Commission election because that is not an exciting race. I had to work with the kids day and night, showing them what could be accomplished if the union was active in this election. I’d sit them down and start in on it, “Look, for you as an operator, or you as a repairman, or service rep., the Public Service election is really the most important race there is.” Once they saw that their working conditions and their livelihoods were better, much better, than they had been before CWA developed a relationship with the Commission, the members became proud and worked very hard at politics.

When I went to Louisiana, the locals that were put under me never contributed to COPE (the AFL-CIO’s national political arm, the Committee for Political Education). Every year after I was assigned to Louisiana, I got a plaque at the International Convention because every one of my locals was 100 percent.

You have to show members a reason to give money to COPE. By law, any money contributed to COPE is over and above union dues and must be hand-collected.

But, see, COPE can only do so much. You can have a state AFL-CIO leader like Victor Bussie in Louisiana who’s very active, but unless you have the contacts yourself, you can’t bring pressure to bear to help your people in CWA. The state body president wouldn’t understand the interrelations and inner workings of the telephone company in the way that I did.

Another thing: I realized at that time that CWA had something special to offer a candidate in any election. Many of our people were professionals at one thing - they spent eight hours a day talking to people over the telephone. An operator gets so adept at listening, when she talks to a voter for a few minutes, she can almost tell you how that person is going to vote.

I was looking for a way in which CWA could get the most mileage from its own membership. The phone bank was made to order. A union leader needs to place his people where the candidate can see them. And the union members need to feel a part of the campaign. Having me collect money from members and get my picture in the paper handing a check to the candidate doesn’t do either of those things. COPE originally set up the phone bank system, but let me tell you in my opinion what’s wrong with the COPE thing. They have it set up where union members call only union members. In my honest opinion, you don’t get the kind of benefit for your union that you get working directly for the campaign. The members don’t feel nearly as close to the campaign. I’ve tried to tell that to COPE.

When CWA ran a phone bank in Louisiana, we first got a list of every registered voter in the precinct, along with his address and telephone number. You just go down, calling everyone on the list. An operator doesn’t identify herself as a union member. She just says, “I’m a volunteer working for the election of so and so. . .”

Where people make a mistake on a phone bank is trying to put too much garbage into each call. And our kids know this. All you need to say is, just a very short thing. I’ve made it up over the years through trial and error, “Hello, my name is Selina Burch. I’m a volunteer working for the election of Hale Boggs for Congress. I’m calling to remind you that three weeks from today is election day and I hope you can go to the polls and will consider voting for Congressman Boggs. Do you need a ride to the polls to vote for Congressman Boggs?”

That’s three times that you’ve got the candidate’s name over to that called person. You’ve got something into the back of that voter’s mind. Somewhere during your little spiel, that person is going to give some indication to the CWA volunteer, “That’s my man, I’m with you,” or “I have no use for him.” Depending on how the person reacts, the volunteer puts a code down on the list beside the voter’s name, then the campaign people know what person they want to get to the polls on election day.

There is nothing technical or mechanical about it. Our people were valuable to the candidate because of their ability to listen and understand how the voter is responding. And telephone operators knew how to keep it simple. It’s not mysterious. Just telephones in a room where people are comfortable and where they’re seated close together so they enjoy the companionship — if they get somebody nasty on the phone, they can turn to the next person and say, “Guess what that s.o.b. said to me?” and laugh it off. I’ve seen it tried at home and people get too discouraged. It’s a team effort.

In 1960, Hale Boggs saw a CWA phone bank in operation. He became fascinated with it. He had never seen anything like it. We started experimenting in that election: we would leave one precinct alone and we would call down the list in the next precinct. The results were astonishing.

Anyway, in 1960, CWA ran a phone bank operation for Boggs and John Kennedy in Louisiana. Boggs was Whip of the House then. CWA always had a big shindig in Washington when the Congressmen were sworn in. Before 1960, Boggs had never been to a CWA function in his life. After we worked with him at home in Louisiana in 1960, he came and he and Lindy (Mrs. Boggs) stayed late until they could see Joe Beirne (then president of CWA) to tell him about how great the Communication Workers of America were. Beirne called me from Washington the next morning to thank me. Boggs and Beirne became very dear friends after that.

I was very active in the Women’s Movement for Kennedy, speaking for him at many AFL-CIO programs. Through that campaigning, and working for Boggs, I got to know many community leaders in New Orleans, people who probably had hangups where labor leaders were concerned, but by working together in a campaign, you get to them personally and erase any bad ideas they may have about “labor people.”

Through this political and community work, I became friends with a man who owned a brokerage firm in New Orleans and who was on the board of directors of the New York Stock Exchange. In Louisiana, general elections are held on Saturday. Since his offices were closed on election days, then, this stock broker would turn over the brokerage house to CWA, all those free phones. We patched in the switchboard and it would be all ours. All in all, politics became a powerful tool I could use to make a place for the union in the state, for individual members and for the whole organization.

Working for Boggs did not have the direct bearing that working in a Public Service Commission election would have. But the company did have great respect for Boggs. You have to remember, the company also understands power and where the power is. Anyone who becomes Whip is in a very powerful position. Boggs generally lined up with labor on bills we wanted passed. I think that some of the company officials, men I worked with, were envious of my friendship with Hale and Lindy, but they could have gone out and worked for him just the same as we did.

While I was in Louisiana, and even after I was called to Atlanta in 1963, CWA ran phone banks for Boggs every time he ran; for Lindy after Congressman Boggs was killed; for Lyndon Johnson; different governors’ races; mayors’ elections in various cities; state legislature elections. I set up phone banks and gave speeches to the membership in all these campaigns.

I learned many, many years ago, that a union could sit and negotiate a contract and have the best contract that anybody could ever have but one stroke of a pen could take everything away from you. If you did not have some say in political races, if you did not elect the right people, this could happen to you overnight. Congress could pass a law tomorrow, outlawing all unions; the President could sign it. Where would you be then?

VI

I came to Atlanta in 1963 on a temporary assignment. All of my jobs have been “temporary.” I came over for a month to relieve a guy who was arguing executive-level grievances with the company. After three months had gone by, at the end of each month they’d ask me to stay another month — the vice president offered me a promotion if I would leave Louisiana and come to the Atlanta office permanently. They started tugging on my heart strings, telling me how much the members needed me settling their grievances in Atlanta. All this garbage about how the women in the union would now have a spokesperson at headquarters, how it was the first time that a woman had been given the “privilege” of settling grievances at that high a level. What they really wanted was somebody who would work 16 hours a day on all the grievances that had piled up. They were so far behind when I came to Atlanta. I was spending every night in a hotel room, just reading through the backlog of grievances. From March through December, I handled, at the executive level, 510 grievances.

You always have to remember that if you are a woman, it’s twice as hard. They want you to work, but only at the job they’ve got laid out for you to do. If you go beyond that, and get into something on your own, then you are “aggressive.” You start hearing, “You’re a throat cutter,” “You’ve changed,” “You’re not what you used to be.”

I decided: well, then, if I’m an aggressive bitch, I’m an aggressive bitch. I didn’t care. I was aggressive on the side of the members and that’s what I was there for. As far as most members are concerned, the union does one thing: fight for their grievances. I honestly feel that any member who has been discharged or suspended or denied a promotion deserves his day in court all the way up through the grievance procedure. That’s the only avenue he or she has. I feel strongly that you go as hard as you can when you are handling grievances.

In June of 1967, a CWA area director named R.B. Porch was elected vice president of District 3. That’s when my life took a backward step. I had strongly supported Porch’s opponent. My first assignment under Porch was to talk with the blacks who worked for Southern Bell in our district and bring them into the union. That was fine with me. But for all his trying to portray himself as a freethinking person, Porch never really wanted me to work too hard at organizing blacks. And he had an assistant, L.L. Bolick, who didn’t like it at all. I did the work the vice president wanted me to do, and all I got for it was cut to ribbons.

You have to understand, before 1965, blacks worked as janitors and elevator operators. When Southern Bell started hiring blacks as switchboard operators, the phones in the CWA office were ringing off the wall. Members of the union were demanding that we stop it, hollering that if niggers came to work, they were going to walk off their jobs.

My answer was always the same: you have the right to walk off your job, but the union will not protect you if you do. Then, when blacks began to show up at union meetings and voting in elections, my home phone began ringing all night. Members calling to shout “nigger lover” into the phone and hang up. It would have been hard enough, if we had been in it together, if I had been getting any support from the union vice president and his people, but I wasn’t. It got to where the first thing I would look for when I came home in the evening would be two double martinis.

Porch had very little vision and his assistant, Bolick, had less. Porch wanted to be a big shot but he never knew how to do the job to get there. He wanted me to build a name for him, but he and Bolick had the idea that you can do union work without ever leaving the office and mixing with the members. They forgot that any power we had came from the members. You have to involve the membership in anything you do — not just votes and money, either. The members have to work in it, whatever it is you are doing.

Porch and Bolick would not allow me to go out and teach in the locals, because they thought that once I had been teaching in a local, that local would belong to me. Union work is not 8:45 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. work. That’s all I heard about, though. “Why did you come in at 9:15, Ms. Burch?” “Where have you been all afternoon, Ms. Burch?” “Why have you not turned in a vacation slip, Ms. Burch?” Have you ever worked for someone who takes pleasure telling you that he is your boss every chance he gets, just to hear himself say it?

I had always been my own woman. In Louisiana when I saw something that needed to be done for the union, I went ahead and did it, never mind if it was 8:45 in the morning or midnight. Now, every time I did something, they struck me down for it. Bolick started slipping memos about my attitude into my personnel file —the secretaries were my friends and they would tell me what was going on. I was threatened with discharge by both Porch and Bolick.

It got worse and worse. By 1969, I was drinking more than was good for me. My health was falling apart. In early 1970, I was in the hospital in Atlanta for a month. These men had no compassion. The whole time I was in the hospital, my secretary was the only one in the district office who called me. The only one that gave a damn. She sent flowers. Those s.o.b.’s went the whole time without calling. While I was in the hospital, I made up my mind that I was going to do something about it. I could have quit and gotten another job, but I had a lot of benefits built up in CWA, retirement, and fringe benefits. And, I’m not made that way that I could just walk off from it. Maybe it’s my craziness, but I felt I should stay and fight them. I felt strongly that one day the members would understand how these guys were and change things.

In the meantime, Lindy and Hale Boggs had told Andrew Young about me. Young had been an assistant to Martin Luther King and was now running for Congress. In 1971, Young asked me to run a phone bank for his campaign. The district office had nothing to do with my work in that election. I worked for Young’s campaign, because I liked Young. He is an intelligent man. I worked for him very quietly, though. I had to sneak off time to do it. I wasn’t about to bother to sit down and explain to Porch and Bolick how my working for Young could benefit the union. They wouldn’t have cared anyway, unless there was some way they would have gotten credit for it, after all the work was done. It would not have helped me any that Young was black. Anyway, Young won and that was that.

Then, in ’73, (then Atlanta Mayor) Sam Massed had taken the check-off away from AFSCME. There was a garbage strike. Most of the union members out on strike were black. While Massed was trying to break the strike, Vice-mayor Maynard Jackson had walked the picket line with the sanitation workers. So, when Jackson announced that he was going to run against Massed, CWA sent a guy down from Washington to meet him and see if CWA wanted to support him.

Porch had decided that I knew how to give a good party. He asked me if I would prepare a cocktail party for Maynard Jackson and the CWA man from Washington. The party was going fine and after a while, Jackson got started talking about his campaign. I had just come into the room, carrying a tray or something or other and I heard him say, “If there is any expert on political campaigning in the world, then she is standing here with us.”

I was thinking, “Oh, God, don’t say me. I’m in enough trouble already.”

Of course, that’s who he requested. The union was more than happy to have me work for Jackson’s election. He had promised to give AFSCME back the check-off and he did. That was how I came to be assigned to work for Maynard Jackson.

When Jackson won, he appointed me to the Civil Service Board. That’s when the fly hit the ointment. The first and third Thursday of every month, I had to be at Board meetings. Bolick didn’t like my being out of the office. He wanted me where he could watch over me, where I wouldn’t make any more friends. He went to Porch and they decided I was spending too much time with the Board. Two days a month! No thought for the good it was doing CWA, my being there where everybody in the world could see CWA represented on the most politically important board in the city. They decided to try to force me to resign from the Board. Bolick wrote me a formal letter demanding that I spell out what the duties of a Civil Service Board member were. I told him he could call City Hall. Then, I wrote my own letter: I charged CWA with sex discrimination.

Well, right away, Washington sent down a man to try to smooth things over. But that wasn’t going to happen. In the meantime, a group of women — women I had known over the years in the union — had gotten together at a CWA convention in Miami and formed a Women’s Movement in CWA. They elected me the chairperson. They didn’t know what I was going through, my personal problems in Atlanta. All they knew was that I was a woman with their same point of view who didn’t mind telling the men in the union to go to hell when it was necessary. It put the union in a bind that I was head of the women’s group.

Before any of this could be settled, it came time for elections. Usually, a regional vice president stays in office for as long as he wishes. Until he is 65, usually. Because he has all the travel expenses and any excuse he needs to visit the local officers and campaign right before the election. That’s the only time Porch paid any attention to the locals, and then only to the officers.

Porch, though, had made one big mistake. A year or so before all this, he decided that I should take over the educational program, a leadership school that CWA runs at the University of Georgia. He didn’t give a damn about the school; he didn’t look over my shoulder and left me to run it however I wanted. When I was assigned to run it, the district office was only allowing 45 people into the program from 95 locals. I opened it up to as many members as the classroom would hold, about 135. Most of the members who came to the school were young, and they were tired of hearing about COPE and organizing, community services and so on and so forth. They had heard all that. They were looking for something lively, something that meant something to them. I wanted to give them that, but at the same time, give them some reason to want to work for the union. I moved things around so that the school was teaching psychology, sex discrimination, race relations, things like that in addition to the usual.

I expected that some good would come out of that teaching, but I had no idea it would turn out the way it did. I was just trying to involve the members.

I may not know much, but I do know a little something about politics. I knew that I couldn’t run for district vice president myself. The union wasn’t ready for that. CWA members looked upon Porch as the politician, back-slapping, “Goddamn, how-ya-doing, greatest guy since Seven-Up” kind of politician. Unbeatable. There was a guy who was the area director of Georgia and Florida, Allen Willis. Willis is a very down-to-earth kind of fellow. People who had been in CWA for a long time didn’t think that a guy like Willis could touch Porch in an election.

Well, Willis won. The way it happened was funny. It was very close. I bought $44 worth of buttons and streamers and led a little parade around the convention floor, hoping for, hell, 10 more votes. That’s how close it was, right down to the wire. The people who voted for Willis at the national convention, those delegates, many of them were the people from the black locals and the kids who had gone to the leadership school. The women and the blacks made the difference and a friend of mine in Washington told me the other day that CWA is still shaken all the way to the top by that election.

Now, I am Willis’ administrative assistant. Bolick reports to me. It kills him just to have to come in to ask me for a favor, or for advice. I guess I could make him punch a time clock every morning, but I’m just not like that anymore.

Porch and Bolick thought I was screwed up, a nut. But crazy or not, I never did forget that little telephone operator out there who is over-supervised to begin with and here the company goes and runs in a speed-up program on her. We just had a meeting today: the company is trying to bring in paid directory assistance in Florida. That’ll mean laying off information operators. If I don’t do something about that, I’m nothing. I’ve got no use. I may have gone after power, but I never forgot where it was coming from.

Porch forgot and he’s out. For now. But I hear he’s travelling around, talking to people about the next election.

Tags

Sean Despereaux

Interview by Sean Despereaux, a former newspaper reporter in Florida and North Carolina and summer intern with the Institute for Southern Studies’ weekly newspaper column. “Facing South.” (1976)