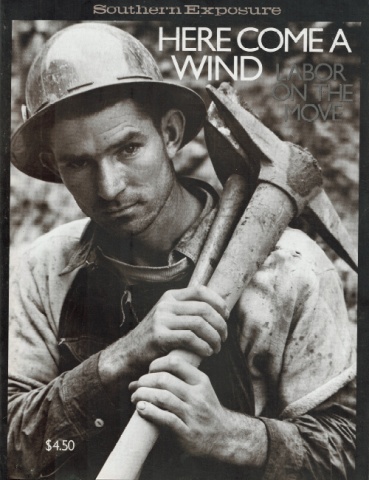

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

Next time you open a bag of Fritos or a pack of cigarettes, think about Marvin Gaddy. Marvin has worked in Olin Corporation's Film Division for over 20 years making cellophane wrapping for just about any product you can imagine. He can't see as well as he used to and still gets those nightmares every once in a while. He's watched the lives of many men change after they came off that second floor. Some got eaten up with tumors and cancer. For some, it got so bad they took their own lives. Others were luckier and got out with only minor nerve problems to remind them of what it was like up there.

The second floor is in the Chemical Building at Olin's Film Division near Brevard, North Carolina, on the edge of the Pisgah National Forest. Built in 1951, the Film Division produces viscose which is extruded, solidified and dried to form cellophane. The second floor houses the xanthation process. Twelve massive barettes are kept in constant rotation, each mixing together 700-800 pounds of ripened alkali cellulose (raw wood pulp and I6 percent caustic acid). Marvin used to add carbon disulfide to the rotating vats, which helped to quicken the process of breaking down the raw wood pulp into a liquid cellophane-like mixture. Nobody ever told Marvin and his fellow workers that the carbon disulfide (CS2) could harm them. But they finally found out. Only then, it was too late.

"A lot of people would leave," says Marvin. "The younger ones would come in there, work a few days, and then they'd invariably get a big whiff of CS2. People would act real unusual, get headaches and think they were getting the flu. After a few overdoses, the nightmares would start coming on them. We'd go in and tell the company, ‘Dammit, you'd better do something about this CS2 stuff.' They'd tell us to get the hell out — 'we don't need you. If you don't enjoy your job, then go home.' Course we didn't have a union back then. And we didn't have Jimmy Reese rummaging through their trashcans and filing all those grievances and complaints."

James Reese is a maintenance man at the Olin plant and chairman of the union safety committee for Local 1971 of the United Paperworkers International Union (UPIU). Each morning, James rises at 4:30 a.m. to greet the day with an hour of playing his organ. From then on, he's like a human dynamo with an instinct for cover-ups that would put Woodward & Bernstein to shame. If he'd been born a few generations earlier, he would have been side by side with the pioneers, wrestling the hills away from the Indians. But today, there are newer and more powerful adversaries to be fought in the North Carolina mountains — like the Olin Corporation.

"The thing about us mountain people, "explains James, "is that we never had to depend on someone else for our livelihood. If a man didn't like it where he was working, he could get his gun and go out in the woods and get him something to eat. Now my daddy, he was what people used to call a 'trespasser.' He'd go out in these government forest lands and get whatever he wanted.

"Some people don't fear losing their jobs no way. They just like to fight and this is what comes out of their tradition. They don't act like mill people, who are always being dependent on the bossman for jobs and food and houses and schools. People around here rely on themselves more. They're more willing to take chances and stand up."

Olin workers had to stand up and fight for more than 30 years before they got the union in at Olin. The battle left a trail of beaten-up organizers, fired union sympathizers, and heart-breaking, one-vote Labor Board election defeats. Finally, in 1971, the union won a contract which included a safety committee to monitor working conditions and the in-plant environment. For the past five years, James Reese has used the committee to help his fellow workers investigate numerous toxic substances: asbestos, carbon disulfide, formaldehyde, tetrahydrofuran, flax dust, noise, radiation, methyl bromide.

"Now this OSHA thing that I'm into, I volunteered for this because it was mine from the word 'go.' I had learned the OSHA standards even before we got our union organized, til I almost had them memorized. I was just kind of interested. It represented a kind of challenge to me because I've seen some of the conditions up there and I've been hurt on the job myself. I’m not sure what set me off. I think it's just the fact that I'm a kind of militant type of character and this way, for once, I had something that they had to listen to. I finally had a law to back me up. "

Congress passed the Williams-Steiger Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 in response to escalating on-the-job injury rates and intense pressure from national unions. The act created the OSHA Administration within the US Labor Department, with the responsibility for inspecting the workplace for hazards and imposing penalties of up to $10,000 when unsafe conditions were uncovered. In addition, the act gave bold rights to affected workers to assist them in cleaning up their plants. It is these workers' rights which are the most important aspect of the law because unions and employees cannot depend on the chronically understaffed and under-financed OSHA Administration to initiate enforcement. Workers can now file a complaint requesting an unannounced inspection, accompany the OSHA inspector during his inspection, demand an investigation of potentially harmful substances, and even challenge the amount of time given a company to clean up recognized hazards.

For James Reese and the other members of Local 1971, OSHA has become more than another law or bureaucratic agency. It is a tool they can use to take matters into their own hands, a weapon they can hold to the company's head to force them to clean up unhealthy conditions.

"I can just talk about getting an inspector in here and the company safety man will about go to shaking, trying to get things straightened out. Of course, it wasn't always that way around here. Back in September of '72, I heard from people that the company was gonna be doing these noise tests, so I went up there with them to see what was going on. This guy got on me pretty hot. He tried to get rid of me, and we got into a regular cuss fight over it. He says, 'You get out of here, you got no business in here.' I says back, 7 represent all the people in this union as their safety man.' He kicked me out of there, but I filed a grievance on it. In the first two steps of the grievance procedure the company says that the contract does not allow that an employee can leave his work station at any time.

"So, then I got all fired up. I threatened to file charges with the federal government through OSHA on it. Well, that scared them, so they sent it up to the highest corporate levels. Pretty soon, a letter comes back from the higher-ups saying that we can watch any. of their tests and also get all the records of what they find. This was just great.

"I was getting a lot of this stuff they were doing. I don't know whether they realized it or not, but I was making a lot of records. That's what I was really after cause records have a way of kinda flying back in your face. And that's what I was doing, getting it down on paper to show what their real attitude is toward safety and health — in spite of those big awards they got plastered all over the cafeteria walls and their reputation as a safe company."

II.

Although the hazards of carbon disulfide exposure were recognized as early as 1851 in France, little has been written about the chemical in the United States. Both liquid and vapor are highly irritating to the skin, eyes, nose and air passages. This local irritation, however, is overshadowed by the serious long-term effects on the body after the chemical has been absorbed through the skin and lungs. High concentrations rapidly affect the brain, causing loss of consciousness and even death. Lower concentrations may cause headaches and giddiness or lung and stomach irritation.

Prolonged repeated exposures to relatively low levels of CS2 affect several parts of the body. Brain damage results in mental abnormalities such as depression, euphoria, agitation, hallucinations and nightmares. Nerve injury can cause blindness when the optic nerve is involved or weakness of the arms and legs when peripheral nerves are inflamed.

In 1943, Dr. Alice Hamilton, a pioneer in occupational health in the United States, described the symptoms of CS2 poisoning in her classic book, Exploring the Dangerous Trades. After studying workers in the newly-blossoming viscose rayon industry, she remarked that the men "knew that a distressing change had come over them, one they could not control. It spoiled life for them, it ruined their homes, it broke up friendships, it antagonized foremen and fellow workers, it made day and night miserable."

The reactions were the same three decades later. Working around the barettes is definitely the nastiest job on the second floor at Olin's chemical building. Nobody likes to do it, but it is essential to making cellophane. After an 800 lb. batch of cellulose (wood pulp) is mixed up with the CS2 for an hour and a half in the barettes, the syrup-like mixture drops down a floor to be aged. Following this mixing process, a vacuum sucks off most of the CS2 fumes.

As Marvin Gaddy remembers: "Sometimes when we'd open those barettes, you get enough fumes to just about knock you out. We'd then take our scrapers and scrape out all that was stuck and there 'd still be a lot of CS2 in it.

"The company had given us testing machines to measure the fumes, but they would only go up to 50 parts per million (ppm). The OSHA standard was at 20 ppm. I'd know that it'd be a lot higher, but there was no way to prove it. Everytime I'd file a grievance on the CS2, I'd just mark it '50 ppm+.' No telling how high it went. I filed over twenty grievances on it. Nothing happened.

"One night I was scraping out a barette and a maintenance man was cleaning out a tank that pumps the CS2. So he takes a gallon or so that was in there and dumps it in a garbage can right near me. And there wasn't enough water in the trash can to cover over all the CS2 fumes. So the fumes is coming out real strong. I was very irritated and went on home. I didn 't go to work the next day, cause I thought I'd taken the flu. My family doctor just said, 'Go see the company doctor.' So Dr. Ryan put me on observation for three months.

"They kept me off my job for 16 months after this thing. Management and the safety department said I couldn't go back to work. Now I'm on another floor; I can't go back there because of my eyes, really because of the CS2. I've been trying for years to prove that my problems come from CS2, but they've been fighting me. My eyes used to be 20I20. While I was working in there I began wearing glasses, but it got worse. One doctor told me the nerves in my eye started drawing the eyeball over to the side and getting it all out of focus.

"I went to a Dr. Trantham down in Greenville. He said it was the most unusual case he'd ever seen. He said that if it's a cataract I got, then hold off for three years and the other eye will develop the exact same way the first one did. Well, I've been waiting around for 5 years now and nothing else happened to the other one. "

"I went to Dr. Sunderhaus up in Asheville. He's an eye doctor. I said, 'Insurance should take care of all these doctor bills!' He said, 'No, no. We'll do this up as an industrial injury for workers compensation. 'Now I guess the company has bought him off. They found out who he was and started sending everybody that had these problems to Sunderhaus. He wrote a letter to the Industrial Commission saying that CS2 had nothing to do with my eye problems. On April 7, 1976 they turned down my claim. I got nothing and it made me mad. "

Marvin's case is far from unusual, and by no means the most mysterious. Take Bobby Roberts, for example. He was in his late 20s and he'd only worked with the CS2 for about a week. He was also with the voluntary fire department down in Etowah. On the Friday night after his first week at Olin, they called him out on a big fire.

"He just never showed up. They went to his house. They found him lying there dead with his gear half on him. No doctors ever said what caused it but we know it was the carbon disulfide. He died just before they started the NIOSH study.”

III.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) was set up by Congress in 1970 as the research arm for the OSH A Administration. At an employee's request, NIOSH inspectors will determine whether any toxic substance found in the workplace is causing harmful effects. Unfortunately, NIOSH does not have enforcement powers.

James Reese had heard about NIOSH investigations at a union training session in Richmond. He'd also been hearing about more strange happenings up on the second floor from Marvin Gaddy and others. So he filed an official request with NIOSH for a health hazard evaluation survey for the CS2.

"This just scared the britches off of 'em," Reese remembered. "They are just afraid that somewhere down the line something is gonna get proved on them, and they'll have to spend a lot of money cleaning it up. There's no laws for testing chemicals put in the workplace, like the Food & Drug Administration or EPA. They put things into practice too quick. They should've checked this stuff in the beginning."

On July 27, 1973, Jerome Flesch, a NIOSH industrial hygienist, came to Olin's Pisgah Forest plant to investigate the CS2. Flesch and his NIOSH team went to the second floor and observed the leaky gaskets and pipes, and the air vacuums that clogged every once in a while.

They also tested to see how much carbon disulfide was in the air when the big barettes were opened for scraping. Like Marvin Gaddy's CS2 tester, the dials on the NIOSH equipment went up as high as they could — except on their machine the limit read 288 ppm. The OSHA standard for carbon disulfide is 20 ppm.

According to Emil A. Paluch, a Polish research scientist: "From the toxicological point of view a concentration of about 300 ppm of carbon disulphide is the amount which exceeds almost everybody's tolerance in a comparatively short period of time and can produce serious pathological changes within a few days."

The scientists from NIOSH could only mark their test results, '288 ppm+.’

Three months later, NIOSH sent down a physician, James B. Lucas, to do a follow-up medical survey on neurological problems with the workers on the second floor. He reported back that 29 men were interviewed, most of whom complained about recurring nightmares, abdominal pains, headaches, dizziness and insomnia. He summed up his findings on nerve problems with a short statement: "A number of bizarre neurological findings were noted." Among his findings were the following:

A 34-year-old man worked 141I2 years in the chemical building prior to his transfer. He has a several year history of numbness, pains, and tingling involving the right side of his face. A neurological consultant for the company diagnosed him with "a typical facial neuralgia.”

A 44-year-old man with 22 years exposure. He has been on leave from work for two years with a vague arthritis-like ailment.

A 46-year-man man with 22 years exposure notes numbness in both his legs, which he attributes to spinal problems and pinched nerves.

A 37-year-old man with 16 years exposure had the onset of a convulsive disorder two years ago beginning with a three day period of status epilepticus. His doctor told him his seizure was due to "a swelled blood vessel in the temporal area.” An extensive report by a neurological consultant hired by the company indicates no such finding to explain the onset of his epilepsy. He is currently depressed by his downgraded position (janitor). His neurological exam was normal.

"That last guy you read about, that was Jimmy Massey," explained Bert McColl, who suffers himself from a rare form of hipbone decay that makes walking difficult. "Massey got this stu ff worse than anybody. They called it epileptic fits for a long time so they wouldn't have to pay no workers' compensation to him. First time it happened, he was just sitting there eating supper with his wife and kids. Then he started having a fit. So the company said, 'If it just happened at home, then it couldn't have anything to do with his work.' Later on, they found all the tumors.

"There was another guy — Herbert Higgins. He was 38, too, in the same shape, started doing the same things. Only they didn't find the tumors in his brain til after he died. Nobody ever laid it to CS2 though. That was before these studies.

"Jimmy Massey is still barely living over near Canton. They give him a few more months before the cancer will eat up his brain. His wife just had a baby recently. The family started runnin' out of money with all the medical bills they had to pay, so the company put Jimmy back to work again. They put him on the janitor crew, going around the plant picking up trash. He'd wander round and round not even knowing what he's supposed to do. He'd sit around by the time dock without even knowing when he should punch out.

'Stogie' Sellers used to work with this stuff, too, until it got him so depressed that he took his gun and killed himself. George Sanders worked with us on the second floor, too. He used to empty all these trashcans full of CS2. Boy, did he get a lot of fumes! I worked around him the week before he died and you could definitely tell that he was in a strain. He was awful bad depressed. He wouldn't say nothing to no one. His wife was pregnant at the time. He died of a shotgun wound one Saturday night. Everybody said it was just an accident."

At the end of April, 1974, NIOSH finally released its health hazard evaluation report for the CS2. The evidence showed that acute exposures to carbon disulfide had been occurring episodically and these exposures provoked the symptoms in the Olin workers. However, the report stated "there does not appear to be sufficient medical evidence at this time to warrant a conclusion that chronic exposure is occurring in a sufficient degree to provoke illness. Without question, several atypical and unexplained illnesses were encountered during the study. Time may eventually resolve these diagnostic problems."

The report recommended that the chemical operators be rotated on a weekly basis to reduce their exposure time. Other workers should be assigned to the area to increase the maintenance of the barrettes and help insure compliance with all safety precautions. Respirators were also recommended, as well as a training program to inform employees about the hazardous properties of working with carbon disulphide. The report concluded with a very disturbing statement: "It is difficult to postulate that such diverse and asymmetric neurological problems are due to common exposure to toxic substances or due to some unusual personal susceptibility. Local problems of this type are probably related to chance distribution."

Marvin Gaddy: "That's all wrong. We can definitely show you why at least twelve out of these twenty-four people have had all these weird problems. They all worked with the CS2. You see, it's really a nerve gas, at least that's what they used it for back in the war. The stuff goes about working on the weakest nerves that you got. Now, my nerves and Bert's are different. He can't walk or move around the way he used to; I can't see too good. "

Bert McColl: "I started going to nerve doctors down at Emory in Atlanta. They said I should never go back to work. But with Social Security and insurance, they say you gotta be 100 percent disabled before they 'll do anything. I left Emory in February of this year. I begged em to let me put in three months time to help in paying the doctor bills before I come back. They tell me that my bones are decaying all around the hips. They won't say for sure that it's cancer, but it could be. Otherwise they're just decayed and gone."

After the NIOSH study was released, some small changes occurred around the Olin plant. At least there were some written records showing what the carbon disulfide had done. The company had to post the report in the plant and some people started reading it and getting their own ideas. Workers started calling James Reese after hours and telling him about health and safety problems that were happening in their departments — fumes, chemicals, machines without guards, trucks without brakes, etc.

Some of the chemical mixers came to James one day with a label that they'd taken off a bag. They said they'd just started using this dusty stuff called Cyclo-Fil, but the labels on the bag had worried them: "Caution — Contains Asbestos Fibers — Avoid Creating Dust — Breathing Asbestos Dust May Cause Serious Bodily Harm." James immediately called up the safety department. But the safety man said there was no asbestos in the plant. "That stuff is called Cyclo-Fil," he calmly reassured James. James persisted and Olin agreed to send the material off to be tested by an impartial party.

Two months later, the report finally came back from the Georgia Tech research scientists. The next day they ordered that all Cyclo-Fil be taken out of the plant. "They also kicked out that purchasing guy who had ordered the stuff," James added with a snicker.

"Another time, some people told me that they'd seen a state inspector in the plant looking over all the company's radioactive equipment. This made me mad cause they'd agreed to inform me whenever they had an inspector come in here. I got into a real darn hassle with Governor Holshouser and others over this. Olin uses beta rays to measure the thickness or thinness of the cellophane as it is being processed. These 'Accuray' scans used to be regulated by the Atomic Energy Commission, but now they're regulated by the N.C. Department of Human Resources. They sneaked a feller in here to inspect these Accurays — that's what I accused them of. I wrote all kinds of letters trying to get a copy of his report. They didn't give it to me till I wrote the Governor. I wanted to get it out of them, even if I had to write to the President of the United States.

"This is all part of it. They thought that they were being real smart. But in my scrounging in the trashcans, I knew the man had already come in here and found all those violations. I had the report before I wrote to anybody.

"They are so dumb. That's all I can figure. Do you think that I'd let this kind of stuff go in the trash can? I'd run it through the shredder, just like Nixon did. Course if there's ever anything that I want to know about this company, I know where all the trash cans are...

"People have been turning up things, all these untested chemicals, like this kepone thing in Virginia. They had to even bury the plant and the St. James River got ruined. I think it's coming to the stage where industry is gonna have to first prove its point. It's not gonna work the way it's been working. Cause people, when they start to see what's really happenin', then they'll take things into their own hands and start dosing these places down.

"The more pressure that's put on them, the more publicity that can get generated, you start to get results from pushing on em, from finding out stuff about kepone and vinyl chloride and asbestos. It's gonna start building, and people aren't gonna stand for it no more..."

IV.

Traditionally, many companies have avoided safety and health problems in bargaining contracts or arbitrating grievances on the grounds that these areas are 'of mutual concern' to both unions and management. Other companies contend that safety and health is an area of 'management prerogative only.' Joint union-company safety committees have been set up as a 'consultative device' for giving suggestions to management. Consequently, the committees haven't been given any decisionmaking power for implementing their 'suggestions.'

For most employees in the South, occupational safety and health means little more than wearing masks and ear plugs. Corporate safety programs have mainly been built on the premise that the workers are to blame for the injuries or illnesses they receive from the workplace. As in the Olin situation, the existence of occupational diseases has historically been denied.

With the passage of the OSHA Act in 1970, companies across the country are finding that they can't get away with paying lip service or petty cash for better working conditions. Workers, like the Paperworkers in Local 1971, are learning that they have rights now, too — to question, to be curious, to complain and demand better treatment. Safety and health on the job is an area that has been neglected for too long — a new area for both employees and unions. Of course, wages are still important, if you're going to be around to spend them or if they don't all go to paying doctor bills.

As the American chemical feast continues, the safety and health committee is emerging as a new structure for industrial self-protection. We can expect that the OSH A Administration will continue to limp along without adequate funds or personnel to carry out the laws they're supposed to be enforcing. Consequently, as James Reese has learned, the only way to get laws for self-protection carried out is by vigilantly enforcing the laws yourself. The companies learned this long ago. They are well protected and they know how to use the laws.

James Reese: “To try and calm me down, the company's now got me sitting around and talking with this Fletcher Roberts guy all the time. I'm his friend when I can use it to my advantage and that's the same way he works it. We know what we're doing to each other.

"Olin brought Fletcher Roberts in here as the new 'Director for Safety and Loss Prevention' right after we started filing all those OSHA complaints. He's supposed to prevent them from losing money. In fact, he used to be the one who inspected all these companies around here for OSHA. I went to school with him, he used to date my younger sister. I know that OSHA and the companies are working together — this don't upset me — my purposes still get served. This company knows, after all the hellraising that we've done, that we're not gonna sit still for some halfway deal.

"It'll scare him to death when I talk about calling in the OSHA inspector, the very people he used to work with. I wonder why? All I can figure is this reason with him. We kept giving Olin such a hard time and I was calling in outside people quite a bit. I wasn't making too many points, but a least things were getting uncovered. Fletcher Roberts has been put in here to soft-soap me and stop all us people because somewhere it's appearing on record in the corporate levels. Somewhere up there in Stamford, Connecticut, somebody don't like it. Cause they figure sooner or later the law of averages is gonna catch up with them and some of this information is gonna get out to the public.

"They worry some about having to spend money for cleaning up, but losing their reputation is what really makes em squirm. "

V.

Marvin Gaddy is still going to work in Olin's Chemical Building every day, although he's not up on the second floor anymore. They won't let him go back. Now he's got an easier job — no fumes, no scraping, no fear. "I may have to leave my department though. Especially on the graveyard shift, I feel what I'm doing, but I just don't see it. Like this morning, I had to pull up aside the road on the way home from work. My eyes started watering and blurring... I couldn't see..."

Marvin still goes down to the new union hall on many mornings to chat and joke and catch up on the companyIunion gossip. The building looks like a church; in fact the members had gotten a church architect to design it for not much money. Everyone treats it with reverence, too. Marvin has watched the union grow out of nothing over 20 years. It's kind of like a kid would be to other people. They mature, put down roots, learn how to do things better, grow up. Something to be savored after you've gone through it.

After he finished talking, he got up and headed toward the door of the union hall. He opened the door, paused and turned back. There might have been a tear beneath his thick-lensed glasses as he spoke:

"All that we've told you is the facts. I've got only four more years to retirement and all I care about is helping somebody else now. What I've said here, I've told all the doctors, all the lawyers, all the company men. But they can't hurt me now.

"When you got a company that's got the kind of money that Olin's got and they go and tell their lawyers to fight on this and we'll feed you — that's the way the world is run. There's some people that get caught and some that don't.... Now Nixon, course he got caught."

Tags

Chip Hughes

Chip Hughes, a former Southern Exposure editor, is on the staff of the Workers Defense League and coordinates the East Coast Farmworker Support Network. (1983)

Chip Hughes, the special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure is an organizer with the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1978)

Chip Hughes, a member of the Southern Exposure editorial staff, and Len Stanley have worked extensively on occupational health issues including organizing with victims of brown lung disease in North Carolina. (1976)

Len Stanley

Len Stanley is an organizer with the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1977)

Chip Hughes, a member of the Southern Exposure editorial staff, and Len Stanley have worked extensively on occupational health issues including organizing with victims of brown lung disease in North Carolina. (1976)