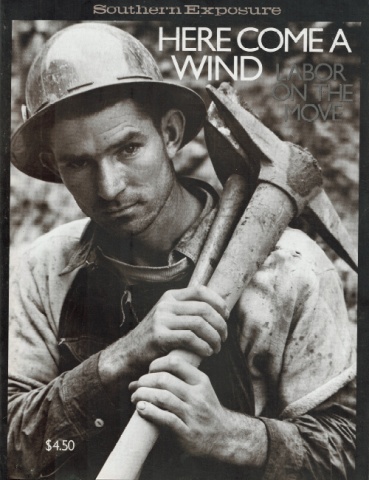

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The problems facing today's Southern labor movement are not unique. Many of the same difficulties have plagued the region for decades, in fact since industrialization first came to the South. Workers have fought for years, for instance, against the divisive force of racism. And industrialists have fought — usually with more success — to strengthen racism to help keep the workers divided and powerless. But occasionally black and white workers have stood together with community supporters and challenged as a class the giant capitalists that controlled the people and natural resources of the area. Often these periods of unity were ended only when local business interests took their guns and violently attacked the workers. The ferocity of the backlash is testimony to the strength of the laborers and of their unions.

One chapter in this violent story occurred in the piney woods of western Louisiana and East Texasin 1911-1913. During the "lumber war," thousands of black and white timber workers formed a racially unified industrial union, the Brotherhood of Timber Workers (BTW), in order to battle the "timber barons" and their powerful Southern Lumber Operators' Association (SLOA).

Eventually, the BTW, an indigenous union of Southern-born workers, voted to affiliate with the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World in 1912. The IWW provided important support —especially in unifying black and white workers around militant industrial unionism and a socialist ideology. But the BTW's strength and solidarity was not created by "outside agitators." The Brotherhood developed as a response of Southern workers to the highly exploitative, extractive industries, which chewed up workers almost as fast as they did the countryside. This remarkable union was founded and led by Southern-born socialists. And it was Southerners who suffered when the BTW was crushed by the lumber operators in 1913.

Life in the Lumber Camps

Industrial capitalism came rapidly to the yellow pine region in the 1880s and 1890s following the repeal of the Homestead Act which had guarded the Southern forests' virginity. It reached its peak in 1910, when 63,000 lumberjacks and millhands were employed by the Louisiana-Texas lumber industry. By 1920, it had left the region ravaged and depressed.

In those forty years, thousands of hill-country whites and Delta blacks poured into the Southern forests, attracted by the relatively high wages offered by industrialists in chronic need of labor. The poor whites generally came from surrounding corn and cotton farms that offered only a subsistence living. In western Louisiana, a large number of the rural refugees were "redbones," a people of "fighting stock," part black, part white, and part Indian who sometimes had a French ancestry like the Cajuns to the south.

Blacks (who formed a majority of the industry's workforce, especially in the lower-paying, more dangerous sawmill jobs) usually came from the plantation areas of the Texas or Louisiana Delta, but some journeyed from as far as the Mississippi and Alabama black belts. Many black fieldhands who fled the plantations of the Louisiana Sugar Bowl and the primitive turpentine camps of Mississippi had experienced gang labor and factory discipline; they also learned about strikes when the Knights of Labor organized in their camps during the 1880s and 1890s. These workers escaped a "slave-like status," but others who came to the pine belt were not so fortunate; they were peons and convicts on lease who were forced to toil in the forests and mills to work off their "debts."

The black workers who migrated from the Gulf Coast sugar plantations had an unusual heritage of militancy. Their ancestors were rebellious slaves brought to the Bayou Teche region of St. Mary's parish to be "broken." According to a Department of Labor study, the sugar workers were of "bad stock" — the "descendants of a particularly vicious lot." These "dangerous Negroes" added to their reputation for militancy in 1886 when they joined the Knights of Labor and struck during harvest time, provoking a violent response from planters.

Most lumber workers, black and white, knew little of the extractive industries or of labor unions; they came to the pine region from their cotton farms unprepared for the changes life and labor in the industrial uplands would demand. In the face of painful dislocations caused by rapid industrialization, these men clung to older traditions: a leisurely, agrarian attitude towards work and production, a grudging insistence on "squatters' rights" to the land and a "primitive” respect for nature. Industrial capitalism in the Southern pine region challenged all of these traditions and demanded conformity to rigorous and alien standards of time, work, discipline and social behavior.

The extreme danger involved in sawmill work made it especially difficult for workers to adjust to the machines. In 1919, even after state safety regulations had been passed, 125 deaths and 16,950 accidents were reported in the Southern lumber industry. Four years earlier the Texas Commissioner of Labor declared that "a large percentage of accidents" in the sawmills were due "to absolute carelessness on the part of the employers."

Sawmill workers, white as well as black, naturally resisted this demanding, dangerous work routine. Many laborers, especially the blacks who usually lacked family ties in the region, simply moved on when they were exhausted or maimed.

Unlike their fellow workers in the sawmills, the loggers were still close to nature. Occasionally work in the forests was suspended in rainy weather. These respites became less frequent, however, as tram-lines extended into the forests permitting extractive operations even in the wet season. The lumberjacks were no longer agricultural workers. They still worked the soil and harvested its products, but now they were destroying, not creating. Mechanized logging was agriculture in reverse.

Despite their hatred of the corporations and their work, many poor farmers found the promise of a $1.50 cash wage for a working day of eleven hours irresistible. A few workers, like the skilled saw filers, received as much as $10 a day, but hundreds of sawmill laborers earned as little as 75 cents a day. Comparatively, the Southern laborer received less pay and worked longer hours than any lumber worker in the country. Union organizers did not focus their protests on the rate of pay, however; wages were still higher than those of turpentine and sugarcane workers and greatly exceeded the income of tenants and croppers. The timber workers complained more frequently about the irregularity of their paydays, the numerous deductions for dubious "benefits" and the control the company maintained through paying in scrip (fake money redeemable only at company-owned facilities). As an employee of the Kirby Lumber Company, largest in Texas, explained, the average worker

"is born in a Company house; wrapped in Company swaddling clothes, rocked in a Company cradle. At sixteen, he goes to work in the Company mill. At twenty-one, he gets married in a Company Church. At forty, he sickens with Company malaria, lies down on a Company bed, is attended by a Company doctor who doses him with Company drugs, and then he loses his last Company breath, while the undertaker is paid by the widow in Company scrip for the Company coffin in which he is buried on Company ground."

Historian Herbert Gutman points out that workers, farmers and townspeople in many American localities at this time opposed the new industrial order because they judged the actions of local capitalists by old, "agrarian" values. The Populists in Louisiana and Texas articulated these values forcefully during the 1890s when they led an attack on the "lumber trust." Conservative Democrats, supported by planters, merchants and industrialists, had destroyed the People's Party in these two states by the turn of the photo from International Socialist century, but this powerful agrarian movement laid the groundwork for a more radical kind of opposition to the "timber barons" that encompassed farmers and workers of both races.

Significantly, the first act of resistance to the industrialists' demands came from the most exploited workers in the Louisiana-Texas pine region, the black millhands. In 1902, Afro-American laborers struck successfully for a reduction of the working day against a sawmill company in Lurcher, La.; a year later these men founded one of the few "Negro locals" of the Socialist Party. In 1904 black workers, assisted by radical organizers of the American Labor Union, engaged in a strike against a lumber company in Groveton, Tex.

The timber workers' first mass collective action took place during the "panic" of 1907 when operators imposed a 20 percent wage cut and a "stretch-out" of the working day. Nearly all of the workers in the Sabine pine region walked out in a "spontaneous general strike" that shut down hundreds of mills. Besides protesting the new demands made by the operators, the timber workers had a list of long-standing grievances: "poor wages and hours, 'gouging' in company stores, payment in scrip, excessive insurance and hospital fees, inadequate housing and sanitation, and irregularity of paydays." Promised wage increases when prosperity returned, most of the workers went back to work immediately. But the workers around DeRidder, La. (later a stonghold of radicalism), held out for several weeks. About this time, "Uncle Pat" O'Neill, a 74 year-old Arkansas coal miner who helped found the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, came to western Louisiana and started publishing a paper called The Toiler in Leesville. His efforts to organize a union were unsuccessful.

In December 1910, Arthur Lee Emerson and Jay Smith, Southern-born lumberjacks, founded the Brotherhood of Timber Workers at a damp logging camp in Carson, La., and began recruiting workers — black and white. They knew that black workers held a majority of the jobs in the Southern lumber industry and that these laborers had been the vanguard in the early protest strikes just after the turn of the century.

J. H. Kirby, leader of the area's lumber operators, warned his mill managers that Emerson was a "rank socialist with some attainments as a scholar" and that his comrade Smith was a "desperate fellow with a great deal of natural ability but little education." Kirby's spies warned him about the presence of these organizers in the piney woods, but the company managers could not stop them. Moving through the mills and camps disguised as insurance salesmen and gamblers, Emerson and Smith managed to avoid the spies and company guards.

In June, 1911, the union organizers felt strong enough to come out of the woods and into the open. They held a convention in Alexandria, La., and formed a constitution modeled after the Knights of Labor. Blacks would be invited to join the union and organize their own locals. The membership would be "mixed" including women, farmers, friends, and supporters. Most importantly, the new Brotherhood of Timberworkers declared itself an industrial union which would follow the example of the Knights, the United Mine Workers and the IWW in organizing all lumber workers into "one big" and not into separate craft unions like the American Federation of Labor.

Shortly after the convention, the Southern Lumber Operators' Association (SLOA), organized after the general strike of 1907, initiated a lockout designed to destroy the BTW. Employers hired Burns detectives to ferret out union men, but the Brotherhood's umbrella of secrecy frustrated espionage activities. Covington Hall, a BTW leader who wrote an important account of the industrial conflict, recalled: "When the lumber barons began their crushing operation in 1911, they found the Brotherhood everywhere and nowhere. It entered the woods and mills as a semi-secret organization with the usual passwords and grips so dear to Southerners, regardless of race." As the lockout continued into the summer of 1911, the lumber corporations began importing strikebreakers and demanding "yellow dog" contracts in which workers pledged not to join the Union. And in July the SLOA closed eleven mills in the "infected area" around DeRidder, La., laying off 3,000 men.

After a summer of vigilant antiunion activity, the Operators Association admitted that it had failed to "break the back" of the BTW. One operator told Kirby that the union had so many organizers in the field (he estimated 500) and had "increased its membership so rapidly" that a more "efficient machine" would have to be designed to combat it. The leaders of the Operators' Association responded by hiring labor spies and by organizing the most efficient "black list" in Southern industry.

Union members who had been shut out and blacklisted managed to survive by picking cotton on the nearby farms of friends and relatives. Manufacturers who were distressed by the lockout's failure to increase demands for yellow pine also worried about the support the Brotherhood received from "lots of merchants, farmers, all kinds of landowners and some officers." They were even more distressed to learn that in September three "redneck" lumberjacks from the BTW attended the Sixth Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World in Chicago.

Late in 1911 many mills in western Louisiana reopened, minus hundreds of blacklisted union men. In the dismal winter months which followed, the BTW went underground and nearly expired. A membership reduced to less than 5,000, a depleted treasury and an exhausted cadre of organizers led the Brotherhood to affiliate with the IWW in May, 1912. "Big Bill" Haywood himself came south from Wobbly headquarters in Chicago to sell discouraged timber workers on the One Big Union. One of the most charismatic figures in the American labor movement, Haywood presented a strong case for affiliation by promising the Brotherhood financial aid, experienced organizers, a union newspaper, and a big injection of confidence and militancy.

The BTW-IWW merger proposed by Haywood was effectively supported by Covington Hall, a remarkably articulate revolutionary. Born in Mississippi and raised in Terrebonne Parish in the Louisiana Sugar Bowl, Hall had witnessed the uprising of the black cane workers in 1877. After helping organize the New Orleans general strike of 1907 — where he grew to hate the conservative AFL craft unionists who dominated the Southern labor movement — he joined the Wobblies. When the Brotherhood affiliated with the IWW, Hall launched a union newspaper called the Lumberjack, which combined the Wobblies' revolutionary industrial unionism and inter-racial emphasis with appeals to the Reconstruction legacy of hatred for Northern carpetbaggers and the Populists' legacy of opposition to corporate monopolies. Hall was one of the IWW's most effective propagandists because he could put anti-capitalist Wobbly ideas into the language of the poor people of the piney woods.

In the spring of 1912, the Wobblies were on the crest of a rapidly breaking wave. Haywood had come to the South fresh from a sensational IWW victory over textile manufacturers in Lawrence, Mass.. The militant tactics of the IWW actually seemed to be working and the voice of radicalism was being heard throughout the land. "When we entered the Louisiana Lumber War," wrote Hall, "the great majority of militants taking part were convinced that the United States was ripe for a mass upheaval; that The Revolution' was just around the corner; and we acted accordingly."

This "Revolution," they felt, had to take place in the factories: it could not win in polling places controlled by "capitalist parties." The IWW cooperated with the Socialist Party in Louisiana and a few other states because its members believed that political action played an important role in workers' struggles. The Wobblies, however, insisted on the primacy of "directed action" at the workplace. Strikes, demonstrations, work stoppages and acts of sabotage would heighten the class struggle and precipitate an apocalyptic "general strike" which would determine the success of the "Revolution" for the workers' control of all industry — what the Wobblies called "industrial democracy."

The strategy of "direct action" as preached by the IWW appealed to "poor white" farmers who had seen their Populist candidates "counted out" by Democratic poll watchers in the 1890s. It was also attractive to transient lumberjacks who failed to meet local residency requirements and to black millhands who were disenfranchised on account of their race. Voting was just another privilege of the white middle class. The Wobblies took a more "direct approach" to the class struggle, argued Jay Smith, a BTW founder:

It is here on the job, in the union hall, that the working class begins to learn that the broadest interpretation of political power comes through industrial organization. It is here on the job, in the union hall, that the workers will learn that the IWW places the ballot in the hands of every man and woman, every boy and girl who works. It is here that the workers will learn that the IWW re-enfranchises the colored man.

Four days after the Brotherhood voted to join the Wobblies, it presented a list of grievances to ten lumber companies in the DeRidder area of western Louisiana. The operators were "aghast" at these demands and they promptly responded with a lockout late in May 1912. In a short time, employers began importing black strikebreakers so that they could reopen their mills with non-union labor. Since armed guards and stockades kept the union men from talking to the scabs, BTW leaders decided to hold rallies outside the mills. Women and children would accompany the male strikers in order to discourage violence.

On Sunday, July 7, A.L. Emerson led a band of 100 strikers and their families to Bon Ami, La., where the huge King-Ryder mill was operating with scab labor. When the group learned that an attempt had been made to assassinate a socialist agitator in that vicinity, the leaders changed direction and headed for a smaller mill town called Grabow. Arriving at a crossroads near the Galloway Lumber Company, Emerson mounted a wagon and began to speak to his followers and a few bystanders around the town. Almost immediately company gunmen opened fire on the group from concealed positions. As people ran for cover, several armed union men fired back at the gunmen in the Galloway Company office. In the ten-minute gun battle that followed, 300 rounds were fired (largely by the company guards) and four men were killed (two unionists, one bystander and one hired gunman). In addition 40people, including several women and children, were wounded. The guards' shotguns "did deadly work," the operator's journal reported, "and the brotherhood members went down in rows." That evening hundreds of angry farmers and workers from Calcasieu Parish armed themselves and gathered at DeRidder; they wanted to avenge those who had been attacked at the Grabow "massacre." After a long night of angry talk, A. L. Emerson and other BTW leaders persuaded the people to disperse and "let the law take its course."

Soon after the gun battle lawmen arrested Emerson and 64 other union men and indicted them on charges of murdering a guard employed by the Galloway Company. The defendants remained in the cramped confines of the Lake Charles jail for two months awaiting trial; they took the opportunity to form a unique "branch local" of the Socialist Party. Meanwhile, experienced Wobbly agitators came into the region to help organize defense movements. The IWW press, with Covington Hall's aid, began a national publicity campaign. Southwest, the industry's trade journal, denounced "this frantic effort...to make it appear as though it were a trial of the 'lumber barons' versus the 'workingmen', instead of a case of the State of Louisiana against a crowd of rioters." Nevertheless, the New Orleans Times Democrat reported that a "dangerous state of opinion" existed in the pine region because so many farmers and workers were outraged by the course the law had taken following the Grabow "massacre."

On the first day of the trial at Lake Charles, 40 workers in J. H. Kirby's biggest mill at Kirbyville, Texas, walked off their jobs to express their solidarity with Emerson and the other defendants; they were all fired and ejected from their houses on the same day. This act of defiance symbolized the importance of the Lake Charles trial to the workers of the Sabine region. Their sense of outrage increased when prosecution attorneys, led by "progressive" Democratic Congressman A.J. Pujo, rejected all potential jurors who expressed sympathy for unionism.

The prosecution's case collapsed when its star witness admitted that the gunmen at the Galloway mill had been drinking before the BTW marchers arrived at Grabow. At one point, the mill owner told his storekeeper to "pour" liquor into the guards until the union men came up. Under the circumstances, Congressman Pujo, who was famous for his investigation of the "trusts", closed his case and hoped that his own clients would not be prosecuted.

It only took the jury a few minutes to find the Grabow defendants innocent. When the verdict was announced, the little courtoom erupted with cheers and the audience spilled into the streets of Lake Charles for a victory parade. That night a "jubilation" meeting took place at the Carpenter's Hall that was attended by members of all the unions and by all seven of the farmers who served on the jury.

The Wobblies reached the peak of their influence in the pine region at this time, but the BTW's membership (about 20,000 in the early summer) continued to decline as the lockout wore on and the blacklist lengthened.

Racial Solidarity

The BTW realized that the growth of industrial unionism in the piney woods depended largely upon the support of black laborers who held a majority of unskilled forest and sawmill jobs. The Brotherhood's attempt to organize black and white workers came at a time when demands for segregation divided the working class and made contacts between the races less frequent and more violent. The workers lived in separate "quarters" in most industrial towns. Social and religious activities were usually divided by race, especially in the years after Jim Crow laws were passed to prevent mixed assemblies. But in these primitive villages, churches, schools and clubs were weak and few in number. There is no evidence of segregation in places where workers frequently congregated — saloons, houses of prostitution, grocery stores, and barber shops. Jim Crow laws were far more important in cities and county seat towns, where there were transportation facilities and public institutions to segregate and established patterns of residency to maintain.

The Wobblies knew that employers had the upper hand in dealing with the race question; if the BTW integrated, the operators could "nigger bait" and play on the blacks' distrust of "rednecks", but if the BTW stayed "lily white", they could use "black legs" with devastating effectiveness. Southwest seemed justified when it predicted the Brotherhood's failure. "Both black and white laborers are employed indiscriminately," the trade journal declared, "and men of wisdom recognize at a glance how impossible it would be to organize the territory under these circumstances." In the summer of 1911 however, Southwest reported that "700 or 800 men and women, a good percent being negro," heard speeches by A. L. Emerson and Cajun firebrand W. D. Fussel. The Brotherhood recruited several thousand members in western Louisiana, the article added, "largely negroes" or white "tenant farmers and loafers about the sawmill places."

Emerson and other union leaders realized from the start that they had to organize the black workers, but they could not ignore the obstacle racism presented. The original BTW constitution provided separate lodges for "negroes" and control of all dues by white locals. The blacks were not satisfied with such arrangements and declared at the second convention that they eschewed "social equalities," but could not "suppress a feeling of taxation without representation." Accordingly, their delegates demanded a colored executive board, elected by black union members and designed to work "in harmony with its white counterpart." But these discriminatory rules against which the blacks protested were later rescinded.

When the Brotherhood affiliated with the IWW in 1912 it added the rhetoric of militant equalitarianism to its official position on interracial recruitment. When Bill Haywood arrived at the Alexandria convention of 1912, he immediately complained about the absence of "colored delegates." Covington Hall explained that the black unionists were meeting in a separate hall in accordance with state segregation laws. "Big Bill" boomed his response: "You cannot possibly do business this way. Bring the colored delegates in and hold the convention."

Haywood told the white delegates that since they worked with blacks they could just as well meet with them in convention. "Why not be sensible about this," he asked, " and call the Negroes into this convention? If it's against the law, this is one time when the law should be broken." The white workers responded favorably to this plea which was echoed effectively by "Cov" Hall. "The Negroes," Haywood wrote, "were called into the session without a murmur of protest from anyone. The mixed convention carried on its work in an orderly way and when it came to the election of delegates to the next IWW convention, black men as well as white were elected." The black union men expressed enthusiasm for the Brotherhood's merger with the IWW and declared: "We have come this far with the Grand Old organization of the B. of T.W. with a true, sincere and loyal intention of going to the end. If she went down as the great ship Titanic did in the Atlantic waters...we are willing to go down with her." The blacks had some reasons to be encouraged. They elected a delegate to the IWW convention, D.R. Gordon of Lake Charles, and a black executive board. What is more, their protests led to the organization of mixed locals, which actually formed in many localities even though black and white union men went to jail for meeting together.

For its brief period of existence, the union provided a new form of association for workers and a substitute for social institutions weakened or made irrelevant by rapid economic and demographic change. One account — by a hostile observer — tells us something about the social role the Brotherhood played for workers of both races. A traveller gave the following account of a BTW meeting he had seen at Merryville, Louisiana, in July of 1912:

I was informed that it was the celebration of Negro emancipation, and that the negroes had given a fine barbecue and that the whites had gone in with them to help out in the financial part and also to celebrate with them as the "Lumber Workers" Union. There were about 2000 or more people upon the ground — about three whites to every two negroes. There was a general mixture of races and sexes, especially when to the sound of the band they collected like a swarm of bees — white, black, male and female — around the speaker's stand.

Then according to the observer, a black minister spoke and introduced A. L. Emerson who related the slaves' struggle for emancipation to the Brotherhood's battle against the lumber trust.

Several conditions prevented racism from destroying the union movement in the piney woods. Firstly, the remoteness of extractive operations in the Sabine region initially created a labor shortage that forced employers to integrate blacks into the work force. Later, this situation hindered the importation of black strike-breakers to a certain extent. Secondly, the Wobblies could apply industrial unionism to an interracial work force that was not seriously divided by craft and wage distinctions. Therefore, white workers were not especially concerned with protecting their privileged job status, as they were in the railroad brotherhoods and the building trades. Finally, and most importantly, the militant industrial unionism of the BTW checked the poisonous growth of race hatred within the ranks of the Southern lumber workers. The organizers of the union, especially the outspoken Wobblies, effectively urged laborers of both races to join together in resisting the demands of the region's industrial capitalists.

The Community Support

In addition to black support, the Brotherhood depended upon assistance from farmers and townspeople. BTW leaders appreciated the importance of rural support. They knew that the Populist movement created a strong anti-capitalist sentiment among many yeoman farmers. They also knew that the lumber corporations forced many of these men and their sons into tenant farming. As one "redbone" tenant from Calasieu Parish pointed out in the summer of 1912: "There is a great deal of feeling here against the sawmill companies on account of their landholding policy." Like many tenants, he wanted to force the corporations to open their "cut over lands" for purchase.

In addition to this long-standing grievance over their "natural right" to the land, the hill country farmers reacted violently to the mill managers attempts to prevent them from peddling their produce in the company towns. Near Fullerton, La., the "redbone" farmers forced the company to allow them access to the town by sabotaging machinery and sniping at company guards. The superintendent of the Pickering Land and Lumber Company told Saposs, the Industrial Relations investigator, that the "redbones" (who were a majority of the white workers at his plant in Cravens, La.) were the "backbone of the 1912 strike," and that the farmers in the area, "who came from the same stock, sympathize with them."

The workers received most of their middle class assistance in established towns not controlled by large corporations. In these older agricultural communities — unlike the newer company towns — the merchants remained free agents, farmers peddled their vegetables in the streets, and professionals served the community rather than the corporation. The workers could preserve ties with their agrarian past and defend themselves against the dislocations caused by industrialization. In some of these towns the people elected officials openly hostile to the corporations.

As industrial strife increased, the corporations supplemented their anti-union tactics with campaigns to undermine the BTW's community support. Company guards and mill managers organized "law and order leagues" to fight the union. These "homespun storm troopers" soon recruited the "best citizens” in the town — doctors, lawyers, merchants and the like — and began to attack the BTW. For example, E. I. Kellie, a candidate for Congress and the leader of the citizen's league, wrote to J. H. Kirby from Jasper, Texas, that he and some of the "boys" had driven Wobbly speakers out of town. "We told them" he said, "this was our town” and that we "were the law and we would not allow no one to speak here that preached their doctrine. Kellie's 'old Ku Klux Klan' are not dead, they were only sleeping and were thoroughly aroused the other night." Moved to eloquence by Kellie's deed, Kirby responded: "The American manhood which your act typified is the sole reliance of their Republic for its perpetuity." In DeRidder, a BTW stronghold, the lumber companies used economic pressure to change the pro-union editorials in the local paper late in 1912. Early in the next year socialist mayor E. F. Presley withstood the efforts made by the Good Citizen's League to oust him, but at about the same time this organization of merchants and businessmen successfully drove BTW organizers out of the town. The participation of the "best citizens" in the law and order leagues of the pine region, as well as in the Councils for Defense and the Ku Klux Klan which followed later, demonstrated that the middle classes of this region had a greater propensity for authoritarian activity than the workers.

Repression

The conflict between the BTW and the SLOA reached its climax at a strike in Merryville, La., in the winter of 1913. A large corporation, the Santa Fe Railroad, moved into this pro-union town and drove a wedge between workers and their white middle class supporters.

The American Lumber Company dominated Merryville, but the workers did not live in atypical company town. Sam Park, the mill manager and part-owner, accepted the Brotherhood and most of its demands. He made his mill at Merryville into a model plant which attracted workers from all over the pine region. The Times Democrat estimated that 90 per cent of Park's 1,300 employees were members of the Brotherhood in 1912. It also reported that "public sympathy is decidedly with the B.T.W." and that "many of the business men in Merryville are members of the Union and display B. of T.W. flags in their windows."

The SLOA denounced Park for "treachery" because' he refused to follow Association orders to shut down his mill during the lockouts of 1911 and 1912 and because he "treated with the union." The Brotherhood was so successful at the American Lumber Company that the SLOA resolved to do away with Park. The Operators' Association kept applying pressure on the Santa Fe, which owned the controlling interest in the American Lumber Company, and in the autumn of 1912 the railroad corporation forced Sam Park out and assumed control of the Merryville complex.

On November 10, 1912, only a week after the celebrated Grabow trial, the new management fired fifteen union men who had appeared as witnesses for the defence in the Lake Charles court, hoping to precipitate a strike for which the Union was unprepared. Jay Smith assembled the Wobblies of Merryville on the tracks of the Kansas City Southern and told them that the Brotherhood could not sustain a long strike because of the losses it had suffered since the Grabow "massacre." Smith put the question to a vote and the most militant workers in the pine region moved to the left side of the tracks. The next morning 1,200 union men struck against the American Lumber Company and the BTW began its last battle.

Phineas Eastman, a Wobbly who helped to organize black workers, claimed that racial solidarity in the Brotherhood reached its strongest point at Merryville. "Although not one of the 15 men fired by the company was a Negro," he wrote, "our colored fellow workers showed their solidarity by walking out with their white comrades and no amount of persuasion or injection of the old race prejudice could induce them to turn scab or traitor."

In the first months of the struggle at Merryville, the workers held their own; they even formed a communal organization (Hall called it the "first American Soviet") that attracted considerable attention in radical circles throughout the country. In the strike's third month, after the mill had re-opened with "scab" labor, the corporation mobilized its community power to crush what was left of the Union. On February 16, 1913, the Merryville Good Citizen's League struck. Organized by the "leading citizens" in the town, led by the company doctor and staffed by Santa Fe gunmen, the League destroyed the Union headquarters, attacked and "deported" several Wobblies, and burned the soup kitchen staffed by female BTW members. The Lumberjack screamed "Class War at Merryville" and charged:

Men born and raised in Louisiana have been beaten, shot and hunted down as though they were wild beasts. Our fellow women workers were driven away from the soup kitchen, the only place where hungry children could be fed, at the point of guns. All of the houses of union men were searched without warrant by agents of the capitalist class.

Hall's paper explained later that "about 300 men had guns," and paraded in the streets up and down the Santa Fe railroad tracks. "Some asked about the law in Louisiana. "Dr. Knight, the leader of the League, "pounded his chest and said this is all the law we want." Knight and his League had indeed taken "the law in their own hands" as the Lake Charles American Press reported. And by midwinter of 1913 the American Lumber Company had exerted enough pressure in Merryville to completely isolate the small number of Wobblies who were still on strike. Having stripped radical workers of their civil rights and separated them from their white community supporters, employers easily crushed the timber workers' last revolt.

CONCLUSION

Although corporation repression completely destroyed the Brotherhood in 1913, the history of the timber workers' struggle should not be written solely as one of defeat. In fact, as the BTW was being crushed by the region's business men and their vigilante henchmen, "some of the most obnoxious causes of dissatisfaction, such as payment in scrip, forced use of company stores, and monthly payments were modified and small wage increases and shorter hours were granted," says Vernon Jensen in his Lumber and Labor. The great sacrifices of the black and white timber workers in their three-year struggle against the powerful "timber barons" were not in vain.

The history of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers conflicts with the conventional stereotypes of defeat and the myths of passive Southern workers. Despite the lack of support offered from official AFL unions, Southern lumber workers took on the most powerful industrial capitalists in the region and organized their own union. As an industrial union, the BTW broke from the pattern of exclusionary AFL unions and opened its membership to women and blacks. The leaders of the Brotherhood - primarily native Southerners — forced the membership to confront the race question and to abandon segregated locals, though AFL union leaders said they were inevitable in the South. But the BTW members' opposition to segregated craft unionism, racism, and corporate capitalism in general did not cost the union its community support.

The Timber Workers stand in a bold tradition of Southern interracial industrial unionism that goes back to the Knights of Labor and the UMW. But the BTW advanced beyond the nineteenth century trade unionism by adopting the IWW's disciplined, "guerilla warfare" tactics and the revolutionary vision of industry controlled by the workers. Drawing upon the deeply-rooted hostility to corporate capitalism initially expressed by the Knights and Populists, the Brotherhood won wide support for a broadly class conscious attack on the alien "lumber trust." It threatened the corporations precisely because its brand of unionism was not limited concessions; blacks and whites, skilled and unskilled, even sympathetic townspeople and farmers — all were brought together in "one big union." It had to be destroyed. But even in defeat, the Brotherhood of Timber Workers' indigenous brand of interracial, industrial unionism represents a powerful weapon for uniting workers and supporters against the corporate elite that still exploits the South's people and resources.

NOTES ON SOURCES

The following were the most important primary sources used in this article: The Commission on Industrial Relations Papers, Dept, of Labor, Record Group 174, National Archives; J. H. Kirby Papers, Univ. of Houston; various articles by Covington Hall in the International Socialist Review, vols. 13-14 and, most importantly, Hall's unpublished manuscript, "Labor Struggles in the Deep South" in Tulane Univ. Library and Wayne State Labor Archives (Detroit). Also the following newspapers: Industrial Worker (Wisconsin); Lumberjack and Voice of the People (LSU, Baton Rouge) and The Rebel (Univ. of Texas, Austin). A full list of footnotes can be found in a much longer version of this article published in the British journal Past & Present, No. 60 (August 1973).

The most important published studies consulted included the following: Ruth Allen, East Texas Lumber Workers (Univ. of Texas Press); Vernon Jensen, Lumber and Labor (Arno); The

Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood (International paperback): Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be ALL: A History of the IWW (Quadrangle paperback); Joyce Kornbluh, ed., Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology (Univ. of Michigan Press, paperback); Roger Shugg, Origins of Class Struggle in Louisiana (LSU Press paperback); Sterling D. Spero and Abram Harris, The Black Worker (Atheneum paperback); and C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South (LSU Press paperback).

In addition the following articles were useful: Ken Lawrence, "Roots of Class Struggle in the South," Radical America, vol. 9, no. 2; H.M. Baron, "The Demand for Black Labor: Notes on the Political Economy of Racism," Radical America, vol. 5, no. 2; Paul Wrothman, "Black Workers in the New South, 1865-1915," in N. I. Huggins, ed., Key Issues in the Afro- American Experience, vol. 2 (Harcourt Brace paperback); George Morgan, "No Compromise-No Recognition: J. H. Kirby and Unionism in the Piney Woods," Labor History, vol. 10; Philip Foner, "The IWW and the Black Worker," Journal of Negro History; vol. LV; Merl Reed, "Lumberjacks and Longshoremen: The IWW in Louisiana," Labor History, vol. 13; Grady McWhiney, "Louisiana Socialists," Journal of Southern History, vol. 30.

Tags

Jim Green

Jim Green is a member of the Radical America editorial collective. He is completing work on a book about the early twentieth-century socialist movement in Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma. (1976)