Buying Death Power

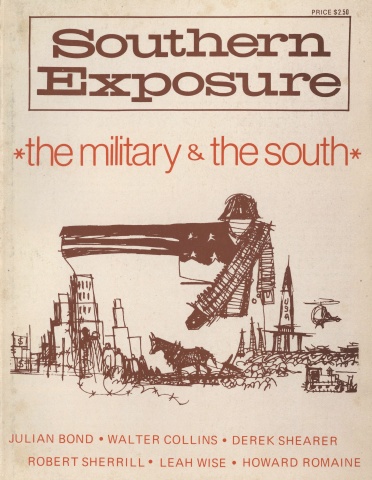

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 1, "The Military & the South." Find more from that issue here.

Robert Sherrill is a precocious southerner, presently living in Washington, who writes with a critical and ironic eye about the shenanigans of our elected “representatives” - reducing them always to the status of mere mortals with feet of sand. His book, Gothic Politics, is an excellent documentary of the Dixiecrat legacy. He writes regularly for The Nation and a number of other publications. He is the author of The Accidental President, and more recently, Why They Call It Politics: A Guide to American Government (Harcourt, Brace, Javanovich) .

Even a casual newspaper reader in one of the most out-of-touch cities in America will be aware that there are really only two men in Congress who watchdog Pentagon spending on behalf of the general public. These two men are, of course, Congressman Les Aspin, a junior member of the House of Representatives, and Senator William Proxmire, both of Wisconsin. Proxmire is probably best known to the South as the fellow who blew the lid off the Lockheed scandal and disclosed that the flying hernia, the C-5A, would cost at least $2 billion more than Lockheed and their allies in collusion, the Air Force, had admitted. Aspin is best known, and hated by defense contractors, for his role in exposing the hilariously inept and costly goings-on at the shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi, where Litton Industries is floundering around trying to manufacture some 35 landing helicopter assault ships and 30 destroyers. Litton’s waste may soon rival Lockheed’s.

The marvelous thing about these two politicians is that there is no logical reason for their successes as watchdogs. Aspin is just about the lowest ranking Democratic member of the House Armed Services Committee, a committee that traditionally has reserved all power to the old bulls. As for Proxmire, he is chairman of a committee that has no legislative powers (no bills come out of the Joint Economics Committee) and that can only obliquely excuse its interest in defense matters. They must rely very heavily on their staffs to turn up the Pentagon’s dirty work, and yet each politician has only the barest skeleton staff to work with—each has only two men who can give only part-time attention to defense budget investigations. Then how do they uncover so much? The answer is in two parts: First of all, both Aspin and Proxmire are born troublemakers, bless their hearts, and they have been around long enough to make friends in the right circles-meaning those circles in which leaks are sprung and secret information comes pouring out. Aspin, for example, made many valuable friends in the Pentagon when he was an aide to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara; many of these old friends nowadays “brown bag’’ information to him on the sly. The other half of the answer is that they really don’t uncover that much scandal. But because everybody else in Congress is sitting on his ass and not uncovering any at all, it only seems that Aspin and Proxmire are doing so much!

In the following interviews, the dull, lethargic, stupid, oppressive, secretive, undemocratic atmosphere hanging over Congressional-Pentagon relations comes through all too clearly. If you wonder why Congress goes along so easily with the Pentagon’s budget, perhaps the mood that rises from this interview, like unclean fog rising from the swamp behind a Standard Oil tanker dock, will give part of the answer.

But there is one other rather chilling note that comes out of the interviews, and it is this: Excellent as these men are, their interest is in getting “the biggest bang for the buck’’-not in slashing the defense budget by, say, one third, as it could certainly stand to be slashed, with no loss to our security. They want to get a dollar’s worth of killing power for a dollar. That is their basic interest. They are thrifty shoppers, not radicals. And yet, such is the benighted mentality of Congress, they are considered radicals.

RS: What is your feeling about the expertise of Pentagon officials who come up here to Congress and say they need so much money for so many weapons? Everybody assumes that the Pentagon has oodles of experts and that it would be almost impossible to out-think them. Is this true?

Aspin: No. There are a couple of reasons this assumption of Pentagon expertise isn’t true. First of all, they don’t have the quality of personnel they used to have. In other words, I think it’s mostly military judgment that is at the root of a lot of the requests. There isn’t any backup of any sophistication. I think the present defense department is very different from the Bob McNamara defense department. Under McNamara there was some kind of an attempt to make a choice on rationality. When the Pentagon came up with a decision in McNamara’s day, there was at least some kind of an attempt to back it up with a rational argument. I don’t think that kind of effort exists now.

But secondly, this whole business about the extent of expertise involved in defense planning is terribly overstated. I think a lot of people believe it’s a highly computerized kind of scientific process. In fact, you know, it’s based upon some very, very simple rules of thumb to determine what our force structure is. If you question those simple assumptions, the whole thing crumbles.

The military mind is one big rule of thumb. They haven’t got any justifications for their budget requests. They say we need 15 carriers. The Navy always says we need 15 carriers. And they say this because the Navy for as long as they’ve lived has been saying we need 15 capital ships. In the old days the battleship was the capital ship, so they said we needed 15 battleships. Now the carrier is the capital ship so the Admirals come to Congress and say we need 15 carriers. Nobody seems to know why 15, but it’s based on history, not on anything rational. You’re laughing, but what I tell you is absolutely true. Fifteen is sort of a standard number. I don’t know how far it goes back. There is an unpublished thesis up at MIT that says it goes back to the Treaty of 1922 in which we were allowed 15 capital ships. Now we’re trying to justify 15 carriers on the basis of that treaty signed two generations ago.

Another thing—it’s a rule of thumb that a division can defend 30 kilometres. Any old idiot can look at a 900 kilometre range and divide by 30 and tell you how many divisions are needed according to that rule. Brilliant. Yet everybody thinks there is some kind of computerized programming that tells you how many divisions are needed. I use the word “needed” loosely. These are World War II standards, as modified slightly perhaps by the Korean War. They’re always based upon the last war. The rules of thumb are based upon the last war.

RS: Wouldn't the kind of weapons available to the division alter the number of divisions needed? After all, weaponry has improved considerably since World War II.

Aspin: It should—you’d think so, wouldn’t you? But nobody over there [at the Pentagon] has ever questioned the number of divisions needed according to the weapons available. They don’t tell you why they need so many divisions, or how they made their decision. They just say that they need 15 divisions, or three.

The whole manpower thing is the most underdeveloped area of defense analysis. We’ve got Rand and Brookings and a lot of universities doing studies on the defense budget. They’ve studied the strategic weapons question until hell won’t have it, with calculations and formulas. Strategic weapons is fun to study; it’s much more scientific and much neater than the manpower question. Nobody studies the manpower question. Consequently, what’s happened is that the support any answers. structure has gone up fantastically-the number of backup guys you’ve got for every guy who’s actually out there toting a rifle. And that’s killing us [killing the budget, that is], and it will kill us more with a volunteer army.

With manpower, we’re bogged down with tradition again. Take for example, there are 11 guys in a squad. So why, we ask, do you need 11 guys? Why not 10 guys? Think how many more squads you could have if you made a study that showed you only needed 10. You ask the Pentagon, why do you need 11 guys in a squad, and they have no answer. They tell you Washington used to have 11 in a squad, or 11 looks great on the parade ground when they’re marching columns. It’s unbelievable. Nobody knows why 11. Suppose you only needed 8; suppose you need 12. Suppose you could make a squad a lot more effective by adding only one more guy. Nobody at the Pentagon ever studies the question. It’s the most underdeveloped expertise and the most expensive part of the defense budget. The thing that they put most emphasis on is strategic weapons, which is really a small part of the budget, money-wise. If you’re worried about the size of the budget, don’t look at strategic weapons, look at manpower.

RS: You’re on the Armed Services Committee. Do you get a chance to ask Pentagon witnesses why they need a certain weapon, or a certain number of weapons, or a certain number of divisions?

Aspin: You don’t get very far in the questioning. You’ve got five minutes to ask. You can get filibustered for five minutes by the guy answering. They do it all the time. You don’t get any answers.

If you want information, you don’t rely on the committee testimony. It’s useless to ask them big questions like that. You ask them much more specific questions: Is the Mark 48 torpedo operational yet? What do you mean by operational? How many volts is it working on? The questions you ask have nothing to do with need. There are certain kinds of questions Congress is concerned about and certain kind they aren’t.

What Congress is worried about is where are you buying it? Does it live up to what it’s supposed to, does it do what it’s supposed to? Those are the kinds of questions Congress concerns itself with. Is it being produced on time? Is there a cost overrun? If you look at Armed Services Committee hearings you’ll see the members are never worried about should we buy 700 F-14’s or 350 F-14’s. The question is, does the F-14 work like it’s supposed to? Is it coming in on a cost overrun? Is it performing right? Who’s got the contract? Are we going to the right contractors?

RS: How many on Armed Services would like to address themselves to the question of need?

Aspin: I’m the only one. Well, maybe a couple of others would be interested. But virtually all the people on the committee represent areas which have defense contracts in them. The questions they ask are relevant for guys representing those kinds of constituencies.

RS: If you do sneak in a question of need, do the Pentagon witnesses lie to you?

Aspin: No, they just don’t answer it. They filibuster for five minutes. Let’s take a case: The Navy is buying some new kinds of submarines—not nuclear, not ballistic. How many should they have? We did some studies when I was in the Pentagon on how many subs we should have, and based on the kind of assumptions you make about what they’re for, basically you should have 60 to 65. It depends on what you want to do with them. We now have 105 submarines of the older kind that these SSN688 attack submarines are replacing. So the hassle has always been between the Navy, which wants to replace them all on a one for one basis, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense, which wants about 60 subs. I asked Admiral Zumwalt how many he wanted to buy. He said it depends on how many the Russians have. That’s the kind of non-answer you get. It doesn’t depend on how many the Russians have. So back and forth we went, chewing up my five minutes, and we didn’t get anywhere. Finally, he supplied something for the record in which he talked about the number of submarines and implied that 105 was the minimum and that he wanted to go above it. There’s no answer. You can’t pin him down. Zumwalt is a savvy person. He understands what you’re talking about. He understood my question. He just didn’t want to answer it. He’s not like some of the chiefs who don’t understand systems analysis, don’t understand the reports. Zumwalt understands the systems but doesn’t want to answer. He wants to keep his options open, so every year we authorize four additional SSN’s or six additional SSN’s or five additional—we don’t know how many we’re ultimately buying but every year we buy three, four, five, six more. But we can’t find out what we’re building towards.

RS: In other words you would like to hear Zumwalt’s reasoning for saying we need so many submarines to face off the Russians?

Aspin: Yes, and you never get the answer. If I were chairman of the Armed Services Committee, I could find out. But I’m number 41 out of 41 members. I get five minutes. But the fact is, I don’t need to ask Zumwalt how he gets his numbers. I can go and ask other people. I can go over to the Center for Naval Analysis and talk to them. I can go to the people at Rand, at Brookings, ex-Pentagon people. There are guys who will tell you what you need to know, but nobody will tell you in the hearings.

RS: Okay, so you can find out some of the real answers to some of the real questions if you go outside the government or establish leaks within the Pentagon. How many people on the committee do that?

Aspin: Well, I would guess four or five.

RS: So the rest of them pass these things in ignorance. They don’t know what the answer is in terms of meeting a threat.

Aspin: Yep. The only exception to that is in the case, I think, of missile strength, vis-a-vis the Russians. In the strategic balance area, there is some concern about how much we need and where we’re going and whether we’re building more or less. This does get discussed. But in any of the general purpose programs, nobody knows. For example, the Navy has a long-range program to buy 30 DD963’s-thirty destroyers out of Litton in Pascagoula, Miss. But nobody has ever, to my knowledge, ever justified why we need thirty DD963’s. Nor have I ever heard within the committee any rational justification for why we should build another carrier.

RS: So what does the lack of rational discussion of weapons needs mean to the people in terms of national defense? Do we have enough, too much, or too little defense?

Aspin: The real problem is that costs are going up faster than effectiveness. For example, the F-4, which is the current fighter plane, costs roughly $4 million apiece. The F-14 which is replacing it will cost 116 million apiece. Nobody in their right mind is suggesting that the F-14 is four times better, but it’s going to cost us four times more. That’s the real problem. I don’t know how to solve it. One way to deal with it, and the way the military and defense departments deal with it, is just to cut back the buy. We buy fewer than we need but at the same costs as the original program. That’s how people like Proxmire can say that we can both cut the defense department budget and increase strength: he’s talking about this problem. When cost growth goes into the budget, automatically the thing pushes toward the panic point. The program goes beyond accounting control, so they cut back. I don’t know how many C-5A’s we were going to buy, but we cut back to 81. The F-lll’s were cut back. They were going to buy nine of Litton’s LHA’s and now they’re going to buy five. Gets to a point where costs get so high that Congress starts to lean on the Pentagon and they panic and cut back.

RS: Which makes their original argument for the necessity of buying nine rather meaningless.

Aspin: Totally kicks it right out. We originally were going to buy 700 F-14’s. Now we’re buying 300 some odd. But what does that say? It says the defense of the country is really a lot weaker.

RS: Either that or they were lying to begin with.

Aspin: Yeah. But in any case, it’s weaker than it could have been had costs been cut down.

• • •

RS: Is Congress kept pretty much in the dark as to what kind of thinking the Pentagon puts into the defense budget? How it arrives at certain budget requests, in terms of the threats to be met?

Proxmire: Yeah, Congress is kept in the dark. There should be public hearings in the executive branch before the budget is finally arrived at and sent to the President. The testimony should be given in hearings before the Office of Management and Budget. The reason there should be public hearings on the public’s budget before the OMB sends it to the President is that after the President puts his okay on the budget, Congress only marginally modifies it.

Another reason the budget should be thrashed out publicly before it gets to the President is that when Congress does make changes in it, the President just ignores the changes. We have frequently pointed out that Congress has cut Nixon’s defense budget by about $16 billion total since he’s been in office, yet spending has remained at about the same level every year-around $76 billion every year. The reason the executive department is able to maintain the budget at any level it wants is that they have these accumulated balances from the past. It’s very confusing. We pass an appropriations bill for maybe $76 billion, but they spend more or less as they choose. What we appropriate doesn’t limit the amount they’ll spend in that year.

RS: How hard is it to get Pentagon witnesses to give you information when you ask why they want a certain weapon?

Proxmire: You’re pressing into an area that we haven’t gone into. This is a Joint Economic Committee, not a military committee or a foreign relations committee. Therefore, we don’t really feel that we have the same kind of responsibility or the same kind of expertise or the same kind of justification to be getting into the strategic foreign policy and military justifications. We are an economic committee. However, when you buy billions and billions of dollars of these things, then the military’s effect on the economy becomes quite obvious and we get into the general question of weaponry need.

On the C-5A, for example, we got into the fact that we had a big cost overrun and that the thing isn’t working, that there were all kinds of mistakes, that procurement was handled very badly. We also in the course of that investigation got some justification of the use of the C-5A. Many people still feel that it is a troop carrier, and of course it isn’t a troop carrier. It is designed to carry out-sized equipment that can’t be carried in the great surplus we have of other military transport planes. You can’t carry big things in anything except a C-5A. There was a very limited purpose for it, and all they needed was 40 of those things and they ordered 120. Why they ordered 120 they never were able to justify.

RS: Was this the first time the question was asked the Pentagon? That is, when they appeared before the Joint Economic Committee, was this the first time they were publicly asked why they needed and why they wanted the C-5A, that you know of?

Proxmire: Yes, and as a matter of fact, I think there were even some members of the Armed Services Committee who didn’t know what the C-5A was supposed to do. Some of them, I think, thought it was a transport for troops.

RS: So Congress is rather ignorant of the things they are asked to spend billions on?

Proxmire: I think that’s right. But I think we’re getting much better. For instance, on the close support aircraft. We developed in the Joint Economic Committee—and by the way, it shouldn’t have been done in the JEC, it should have been done in the Armed Services Committee—we developed information that showed gross duplication on this aircraft. We have a very good, young analyst, Roxx Hamachek, a hell of a bright guy, who did some good hard work in determining that there were actually three different planes being requested—one for the Marines, one for the Air Force, one for the Army—all of which were designed to do the same thing. Two of these planes cost more than the third and were far less efficient than the third. But each one of the services was trying to get its own plane. We testified before the Armed Services Committee, and as a result they accepted our position en toto. Now, that discovery shouldn’t have been left up to an economist, which Hamachek is, and a chairman of a committee like the Joint Economic Committee. We shouldn’t have had to come before the Armed Services Committee and testify. It should have been done by the ASC in the first place. But they do deserve a lot of credit for changing their mind.

RS: Obviously part of the Armed Services Committee’s ignorance comes from an inadequate presentation by Pentagon witnesses.

Proxmire: I agree with that. Let me give you a couple of examples. There is a hell of a lot of money in the defense budget-people say $2 to $3 billion—for the CIA. The damn thing is so poorly analyzed that this never comes out. Or nobody seems to know where it is. There is a lot of money in the budget for military foreign aid. Military foreign aid is now $6 billion. Only about a billion of that, a little more than a billion, is in the regular foreign aid budget. Much of the rest of it is in the defense budget, and yet it is so badly analyzed that an enormous amount of the money is never discussed when their witnesses come to Congress.

On the other hand, when McGovern comes forward with a budget-as he did during his campaign—or Urban Coalition with their Counter-budget or Brookings Institution, they start with what our defense responsibilities are. Our security responsibilities. We have certain responsibilities in regard to NATO, certain responsibilities in regard to the continental United States. We have a demand, therefore, for certain general purpose forces. We have a strategic deterrent we have to build. You start from the bottom and say how much does it cost to do this and this and this. Brookings does that. Urban Coalition does that. McGovern does that. But we don’t get that from the Defense Department when they come up. They don’t break it down into its basic, fundamental military ingredients. They are afraid to do it because they are hiding a lot of stuff in this big budget which was never really discussed or examined publicly before.

RS: Do you think the Pentagon has any better analysts, defense experts, than you have or that the chairman of the Appropriations Committee has?

Proxmire: One of the unfortunate aspects of the Appropriations Committee is that they just don’t have anybody to do this job [appraise the defense budget]. They have two people to handle the entire defense budget. These guys are damned competent people, but they are really harried.

RS: How many do you have on the Joint Economic Committee?

Proxmire: Well, on the Foreign Aid Appropriations Subcommittee we have one-half guy. On the Joint Economic Committee we have two guys, but of course they are doing other things, too. They just work on the defense budget part time.

RS: How many do you need?

Proxmire: I’ve been trying to get . . . Let me tell you a story because I think it’s pretty interesting. We had a leak out of the Pentagon. I forget what weapons systems we were challenging, but at any rate we found out that their own Office of Systems Analysis said it wasn’t efficient and wouldn’t work. We got this leak that the Office of Systems Analysis had recommended against the weapon.

Mel Laird called up. He was very nice about it, but he complained, ‘Now, look, Bill, you are just going to destroy the Office of Systems Analysis. You used what they told you and now I’ll never be able to use them again.’ He said, ‘Why don’t you develop your own office of systems analysis? You wouldn’t need a lot of people.’

I thought that was a pretty good idea. At least we would be independent. I thought we could do it with three good people. For that we’d need $125,000. So I asked for that, and I got $30,000. What always happens when you get $30,000? What the hell, you hire another economist, which helps a little but not nearly to the extent that you had been planning. It’s hard to set up something like that. The other committees say you’re building an empire. They say you’re getting into their area. So they cut you down.

Robert Sherrill

Robert Sherrill is a precocious southerner, presently living in Washington, who writes with a critical and ironic eye about the shenanigans of our elected “representatives” - reducing them always to the status of mere mortals with feet of sand. His book, Gothic Politics, is an excellent documentary of the Dixiecrat legacy. He writes regularly for The Nation and a number of other publications. He is the author of The Accidental President, and more recently, Why They Call It Politics: A Guide to American Government (Harcourt, Brace, Javanovich) . (1973)