1957: The Swimming Pool Showdown

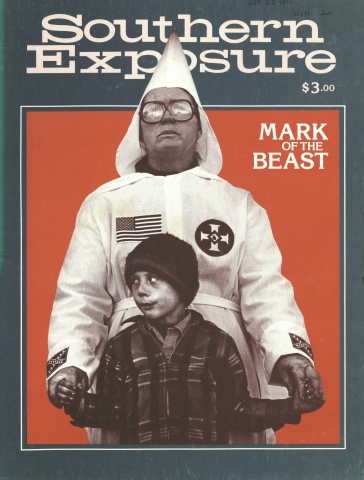

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

When I got out of the Marine Corps, I knew I wanted to go home and join the NAACP. In the Marines I had got a taste of discrimination and had some run-ins that got me into the guardhouse. When I joined the local chapter of the NAACP it was going down in membership, and when it was down to six, the leadership proposed dissolving it. When I objected, I was elected president and they withdrew, except for Dr. Albert E. Perry. Dr. Perry was a newcomer who had settled in Monroe and built up a very successful practice, and he became our vice president. I tried to get former members back without success and finally I realized that I would have to work without the social leaders of the community.

At this time I was inexperienced. Before going into the Marines I had left Monroe, N.C., for a time and worked in an aircraft factory in New Jersey and an auto factory in Detroit. Without knowing it, I had picked up some ideas about organizing from activities around me, but I had never served in a union local and I lacked organizing experience. But I am an active person and I hated to give up on something so important as the NAACP.

So one day I walked into a Negro poolroom in our town, interrupted a game by putting NAACP literature on the table and made a pitch. I recruited half of those present. This got our chapter off to a new start. We began a recruiting drive among laborers, farmers, domestic workers, the unemployed and any and all Negro people in the area. We ended up with a chapter that was unique in the whole NAACP because of its working-class composition and its non-middle-class leadership. Most importantly, we had a strong representation of returned veterans who were very militant and who didn’t scare easily. We started a struggle in Monroe and Union County to integrate public facilities and we had the support of a Unitarian group of white people. In 1957, without any friction at all, we integrated the public library. It shocked us that in other Southern states, particularly Virginia, Negroes encountered such violence in trying to integrate libraries.

We moved on to win better rights for Negroes: economic rights, the rights of education and the right of equal protection under the law. We rapidly got the reputation of being the most militant branch of the NAACP, and obviously we couldn’t get this reputation without antagonizing the racists who are trying to prevent Afro-Americans from enjoying their inalienable rights as Americans. Specifically, we aroused the wrath of the Ku Klux Klan, and a showdown developed over the integration of the swimming pool.

The Ku Klux Klan Swings Into Action

The swimming pool had been built with federal funds under the WPA system and was supported by municipal taxation; yet Negroes could not use this pool. Neither the federal government nor the local officials had provided any swimming facilities at all for Negroes. Over a period of years several of our children had drowned while swimming in unsupervised swimming holes. When we lost another child in 1956 we started a drive to obtain swimming facilities for Negroes, especially for our children.

First, we asked the city officials to build a pool in the Negro community. This would have been a segregated pool, but we asked for this because we were merely interested in safe facilities for the children. The city officials said they couldn’t comply with this request, for it would be too expensive and they didn’t have the money. Then, in a compromise move, we asked that they set aside one or two days out of each week when the segregated pool would be reserved for Negro children. When we asked for this they said that this too would be too expensive. Why would it be too expensive, we asked. Because, they said, each time the colored people used the pool they would have to drain the water and refill it.

They said they would eventually build us a pool when they got the funds. We asked them when we could expect it. One year? They said no. We asked, five years? They said no, they couldn’t be sure. We asked, 10 years? They said that they couldn’t be sure. We asked finally if we could expect it within 15 years and they said that they couldn’t give us any definite promise.

There was a white Catholic priest in the community who owned a station wagon, and he would transport the colored youth to Charlotte, North Carolina, which was 25 miles away, so they could swim there in the Negro pool. Some of the city officials of Charlotte saw this priest swimming in the Negro pool and they wanted to know who he was. The Negro supervisor explained that he was a priest. The city officials replied they didn’t care whether he was a priest or not, that he was white and they had segregation of the races in Charlotte; so they barred the priest from the colored pool.

Again the children didn’t have any safe place to swim at all — so we decided to take legal action against the Monroe pool.

First we started a campaign of stand-ins of short duration. We would go stand for a few minutes and ask to be admitted and never get admitted. While we were preparing the groundwork for possible court proceedings, the Ku Klux Klan came out in the open. The press started to carry articles about the Klan activities. In the beginning they mentioned that a few hundred people would gather in open fields and have their Klan rallies. Then the numbers kept going up. The numbers went up to 3,000, 4,000, 5,000. Finally the Monroe Inquirer estimated that 7,500 Klansmen had gathered in a field to discuss dealing with the integrationists, described by the Klan as the “Communist- Inspired National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.” They started a campaign to get rid of us, to drive us out of the community, directed primarily at Dr. Albert E. Perry, our vice president, and at myself.

The Klan started by circulating a petition. To gather signatures they set up a table in the county courthouse square in Monroe. The petition stated that Dr. Perry and I should be permanently driven out of Union County because we were members and officials of the Communist-NAACP. The Klan claimed 3,000 signatures in the first week. In the following week they claimed 3,000 more. They had no basis for any legal action, but they had hoped to frighten us out of town just by virtue of sheer numbers. In the history of the South, in days past, it was enough to know that so many people wanted to get rid of a Negro to make him take off by himself. One must remember that in this community, where the press estimated that there were 7,500 Klan supporters, the population of the town was only about 12,000 people. Actually, many of the Klan people came in from South Carolina, Monroe being only 14 miles from the state border.

“HE GOT THAT HOOD.’’

The boy’s name I don’t remember but he was crippled, he walked like he had a short leg. He made this expression, “I reckon I’d do most anything to get me enough money to go to that dance tonight.”

Well, Iron Pete, he heard him, he said, “What did you say?”

He said, “I’d do anything to get me some money to go to that dance tonight.”

He said, “If you get one of them hoods” — they still passing through — “off one of them Ku Klux we’ll see that you go up there in grand style.”

And everybody laughed, nobody paid the boy any attention, they just thought it was a statement being made. He toddled out there and caught a Ku Klux by his hood — it was tied around his neck like a bonnet — and liked to pulled him out of that jeep. But he got that hood. And the procession did not stop. He brought that hood back to Auburn Avenue and dropped it on the sidewalk and said, “Here it is.” And how much money he got I don’t know but I know he got somewhere about 10 or 15 dollars cause boys just kept throwing dollars and half-dollars.

And I didn’t want to be in no riot because I was a little kid when the other riot was here in 1906 I can remember it very vividly. I got my hat and coat and caught the streetcar cause I waited for the Ku Klux to get up reinforcements and come back and tear up Auburn. But nothing ever happened.

— a black barber talking about an incident from the mid-’30s to WRFG’s Living Atlanta Project

When they discovered that this could not intimidate us, they decided to take direct action. After their rallies they would drive through our community in motorcades and they would honk their horns and Fire pistols from the car windows. On one occasion, they caught a colored woman on an isolated street corner and they made her dance at pistol point.

At this outbreak of violence against our Negro community, a group of pacifist ministers went to the city officials and asked that the Klan be prohibited from forming these motorcades to parade through Monroe. The officials of the county and the city rejected their requests on the grounds that the Klan was a legal organization having as much constitutional right to organize as the NAACP.

Self-Defense is Born of Our Plight

Since the city officials wouldn’t stop the Klan, we decided to stop the Klan ourselves. We started this action out of the need for defense, because law and order had completely vanished — because there was no such thing as a Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in Monroe, North Carolina. The local officials refused to enforce law and order and when we turned to federal and state officials to enforce law and order they either refused or ignored our appeals.

Luther Hodges, who was later Secretary of Commerce, was the Governor of North Carolina at that time. We first appealed to him. He took sides with the Klan; they had not broken any laws, they were not disorderly. Then we appealed to President Eisenhower but we never received a reply to our telegrams. There was no response at all from Washington.

So we started arming ourselves. I wrote to the National Rifle Association in Washington, which encourages veterans to keep in shape to defend their native land, and asked for a charter, which we got. In a year we had 60 members. We had bought some guns too, in stores, and later a church in the North raised money and got us better rifles. The Klan discovered we were arming and guarding our community. In the summer of 1957 they made one big attempt to stop us. An armed motorcade attacked Dr. Perry’s house, which is situated on the outskirts of the colored commu- nity. We shot it out with the Klan and repelled their attack and the Klan didn’t have any more stomach for this type of fight. They stopped raiding our community. After this clash the same city officials who said the Klan had a constitutional right to organize met in an emergency session and passed a city ordinance banning the Klan from Monroe without a special permit from the police chief.

At the time of our clash with the Klan only three Negro publications — the Afro-American, the Norfolk Journal and Guide, and Jet Magazine — reported the fight. Jet carried some pictures of the self-defense guard. Our fight occurred two weeks before the famous clash between the Indians of Robeson County and the Klan. We had driven the Klan out of our county into the Indian territory. The national press played up the Indian-Klan fight because they didn’t consider this a great threat — the Indians are a tiny minority and people could laugh at the incident as a sentimental joke — but no one wanted Negroes to get the impression that this was an accepted way to deal with the Klan. So the white press maintained a complete blackout about the Monroe fight. After the Klan learned that violence wouldn’t serve their purpose they started to use the racist courts. Dr. Perry, our vice president, was indicted on a trumped-up charge of abortion. He is a Catholic physician, and one of the doctors who had been head of the county medical department drove 40 miles to testify in Dr. Perry’s behalf, declaring that when Dr. Perry had worked in the hospital he had refused to file sterilization permits for the County Welfare Department on the ground that this was contrary to his religious beliefs. But he was convicted, sentenced to five years in prison, and the loss of his medical license. □

This account of how the black community, in Monroe, North Carolina, armed for its defense is excerpted from Negroes With Guns by Robert F. Williams. As president of the Monroe NAACP, Williams organized a heated and protracted struggle, beginning in the mid-1950s, to end discrimination in housing, employment and public facilities. Those organizing drives soon made Monroe’s black community the target of Ku Klux Klan attacks. Police often accompanied the night riders, leaving no legal protection for the town’s black citizens.

The community armed for its defense, although Williams’ rhetoric of self-defense was often mistaken and distorted to mean meeting Klan violence with violence. But he spread his message far and near with his own publication, The Crusader. Williams’ leadership soon drew the attention of both the media and established civil-rights figures including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP.

During a Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee-led demonstration at the county courthouse in 1961, an angry mob of several thousand whites attacked demonstrators and followed protestors into the black community. A white couple, caught by armed blacks inside the black community, was rescued by Williams, given refuge in his home and later released unharmed. Charged with kidnapping the couple, Williams fled to Cuba. He later traveled to Algeria and China, where he published The Crusader in exile.

Williams returned to the United States in 1969 and to North Carolina after a lengthy extradition proceeding which ended in 1976. The charges against him were dropped. He now resides in Michigan and is a campus lecturer.

KU KLUX

They took me out

To some lonesome place.

They said, “Do you believe

In the great white race?”

I said, “Mister,

To tell you the truth,

I’d believe in anything

If you’d just turn me loose.”

The white man said, “Boy,

Can it be

You’re a-standin’ there

A-sassin’ me?”

They hit me in the head

And knocked me down.

And then they kicked me

On the ground.

A klansman said, “Nigger,

Look me in the face —

And tell me you believe in

The great white race.”

— Langston Hughes

Tags

Robert Williams

As president of the Monroe NAACP, Williams organized a heated and protracted struggle, beginning in the mid-1950s, to end discrimination in housing, employment and public facilities. Those organizing drives soon made Monroe’s black community the target of Ku Klux Klan attacks. Police often accompanied the night riders, leaving no legal protection for the town’s black citizens.