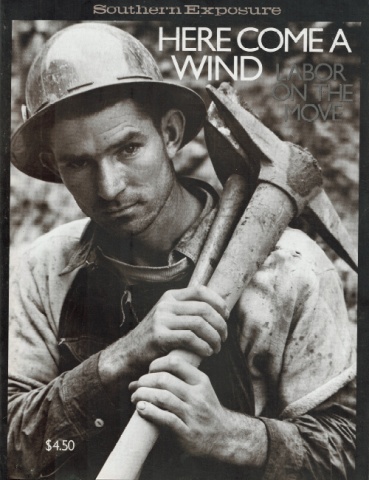

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

John L. Lewis was not in the habit of being pushed around by anybody. Not even the President of the United States. In the height of World War II, when the whole country mobilized to fight the Nazis, John L. pulled his miners out on strike and threatened to stop the engines of America's war production. The Bituminous Coal Operators Association (BCOA) would not renew their contract with the United Mine Workers, and war or no war, Lewis was not about to be denied the greatest weapon organized labor (and particularly industrial unionism) has against recalcitrant employers — the ability to withhold in unison the workers' labor and shut down an industry. The pressure against Lewis was enormous, but not even the pleadings of President Roosevelt that the strike jeopardized the war effort would change Lewis' position. He was determined that this national crisis would not, like the Depression, cripple the union that so many had fought to build. Finally, in mid-1943, the federal government used its powers to seize the nation's mines and force the operators to sign an agreement with the UMWA that, with a series of further strikes, brought the wage changes Lewis wanted. It was an impressive victory that Lewis would not let the industry or the government forget.

In the spring of 1946, the short, post-war contract with the BCOA expired and again the owners refused to sign an agreement with the UMWA. They considered Lewis' demand for an unprecedented industry-sponsored Welfare and Retirement Fund to be outrageous. But to Lewis, the Fund's ability to provide miners adequate medical care and pension benefits was a long-overdue necessity in the nation's most dangerous industry. In his typically florid style, he lambasted the coal operators:

"You aver that you own the mines," he told the operators. "We suggest that, as yet, you do not own the people...We trust that time, as it shrinks your purse, may modify your niggardly and antisocial propensities."

The confrontation that resulted dwarfed even the 1943 skirmishes. For fifty-nine days, the miners remained on strike until the government again chose to intervene on the grounds that "basic industries, such as steel and electric power, were threatened with paralysis" and the war recovery effort jeopardized. Again Lewis had timed his move perfectly, winning a tremendous victory for the union. Under the novel agreement between the United States and the United Mine Workers (which the industry eventually signed), Union-appointed safety committees and the Welfare and Retirement Fund were established as vehicles for the protection and health care of the miner and his family.

As a part of that unique contract, the government agreed to undertake a massive survey of existing health and welfare conditions in the mining towns from Wyoming to West Virginia. The study lasted 10 months and involved teams of doctors, engineers, social service specialists and photographers in exploring everything from outhouses to churches. The end product appeared as a 300-page collection of charts and commentary entitled "A Medical Survey of the Bituminous Coal Industry." What brought the report to life, however, was the photography of Russell Lee.

Russell W. Lee had already made a name for himself when the government commissioned him to photograph the coal camps of America. With Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein and Marion Post Wolcott, Lee had documented the nation in the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration, perfecting in the course of his work, a style of photography that lets the details of simple life express its deepest meaning.

On the suggestion of historian Barry O'Connell, who knew we were preparing this section on Harlan County, we traveled to Washington, DC, to explore Lee's photo files in the National Archives. What we found was truly astounding. Some 8,000 photographs took hold of the miners' lives, moment by moment, revealing the anxieties, the harshness, the easy-going humor, the hard work, the hopes and needs, the good times with friends, the bonds of brotherhood that would make a union strong. There seemed no better way to dispel the monotonous character conveyed by the Bloody Harlan stereotypes than to present in these limited pages Russell Lee's portrait of one family.

Blaine and Rhoda Sergent let Lee stay with their family for several days in Harlan County. They lived in the camp of the PV&K Coal Company, shopped in their company store, worked in their mine. The Sergents' oldest son worked in the same mine and lived with his wife and son (pictured above) just next door to his parents. Another married son lived in the coal camp in Verda and worked in the mine there. Rhoda Sergent spent her days doing chores around the house, handicapped by the lack of running water, refrigeration or electricity. The children each had their daily responsibilities but always managed to find time for the simple games their dirt front yard would allow.

The life of the Sergent family contrasts sharply with the excitement and glamor of John L. Lewis' high-level negotiations. But without them, Lewis was nothing. His power depended on their everyday dreams and devotion to his judgement about the way to achieve them. John L. Lewis might be able to face down the President of the United States, but ultimately it was up to miners like the Sergents to create the means of surviving day to day, generation to generation.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.