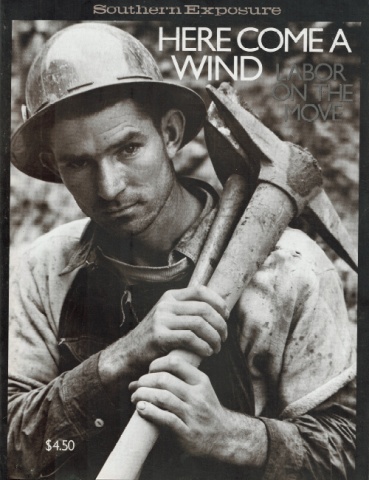

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

"The coal operators would think they got the union crushed, but just like putting out a fire, you can go out and stomp on it and leave a few sparks and here come a wind and it's going to spread again." — Hobart Grills Evarts, Kentucky, 1974

William B. Jones came from an old mountain family. Like many young mountain men at the turn of the century, he went to work in the coal mines while still in his teens; in 1902, at age 19, he joined the United Mine Workers (UMW). The coal industry boomed during World War I and continued to do well in the early twenties. For Jones and others, work was plentiful and the pay good.

But by the end of the 1920s, even before the nationwide crash in '29, the coal industry began to fail. The peak price for coal, over $4 a ton in 1920, steadily declined to $1.73 a ton in 1929. Late in the summer of 1930, William B. Jones lost his job in the Southern Ohio coal fields and moved his wife and seven children to Harlan County, Ky., in hopes of finding work in the mines. His life would never be the same.

On January 1, 1929, the railroads raised freight rates for Harlan operators who sold their coal on the Great Lakes market. That increase, coupled with the falling price of coal, left the Harlan coal industry in trouble. Producers instituted new wage cuts, sold out, or worked only when orders came in. The big mines, owned by Ford, US Steel, International Harvester, Detroit-Edison, and Peabody, survived while many mines backed with less capital closed down.

When W. B. Jones reached Harlan, he found wages far below normal and jobs almost nonexistent. He moved his family from town to town, up the Clover Fork River that cuts through the county, until he finally got a job with the large Peabody Coal Company mine at Black Mountain.

It must have come as a shock to a man who had paid UMW dues for 29 years to find no active union in the Harlan County fields. But if he had his mind set on organizing, he could have picked no better spot than the Black Mountain camp. The Peabody miners were the last to give up their association with the UMW when the union left the county in 1924 after its brief five year stay. It was well known that the men at Black Mountain were the most radical proponents of organization.

In early February, 1931, in the dead of night, 53 men secretly gathered in front of an abandoned mine near the Black Mountain camp. Their purpose was to reorganize the union in southeast Kentucky. Every move had to be carefully planned, for discovery by the operators meant certain dismissal and an instant “blackball" from any mining job in the county.

As Chester "Red" Poore later recalled, W. B. Jones "was the main man trying to organize...he handled the whole damn thing...You'd be screened as you came to take your oath...One of the guys that went in the bunch turned out to be a thug here — carried a gun against us. He took the United Mine Workers obligation same as I did, sure did. Everybody was welcome. Hell, you weren't screened too bad, but they'd screen you.

"We met here in the hollow one night....Then it seems like we met down around Verda, then the next night we met somewhere else. The next night was the big night at Pounding Mill....Great big place — could have been a corn patch, potato patch or anything. And one stump cut out, about as high as that chair. And Jones stood on that stump, making him taller than everybody else.... They'd bring the meeting to order and tell you to gather up as close as possible, so we could hear every word he said, see....We'd all take the obligation same night, same time....You're supposed to stick by the union obligation, and that's it."

By mid-February, the men began seeking help from the international union. Johnson Murphy, a black miner from Evarts, wrote UMW President John L. Lewis, pointedly asking what the union would do for his wife and family "if they kill me for organizing." For awhile it looked like the national organization would help. William Turnblazer, president of District 19 covering southeast Kentucky and east Tennessee, and international representative Lawrence "Peggy" Dwyer both issued a call in the February 15th issue of the UMW Journal for the 20,000 men in their district to organize. At the same time, Turnblazer distributed a circular in the fields that blamed the miners' hard times on "the insane policy of the coal operators in selling coal below the cost of production" and urged the miners "to fight and fight and fight against this terrible degradation." He called for a UMW "rebirth meeting" in Pineville, Ky., on the first of March.

The bitterness caused by yet another wage cut on February 16, and the promise of national support, strengthened the union's appeal to the distraught miners. Rank and file meetings had expanded beyond Black Mountain into the coal camps following the railroad tracks toward Harlan Town. By March 1, the Black Mountain union had grown from 53 lonely men to a movement involving hundreds of people and an indigenous energy that the international union could not contain.

Two thousand miners jammed into the Gaines Theater in Pineville that Sunday afternoon to hear a speech by Philip Murray, Vice President of the UMW. Hundreds more gathered outside the hall, unable to get seats or standing room for the "rebirth meeting" of the union. But far from being a meeting between the union leaders and the rank and file to discuss organization in District 19, the March 1 meeting produced only confusion. The events of the past month in the county and the past six years in the union made it impossible for the Harlan miners and UMW officials to understand each other.

Reflecting the weakened state of the American labor movement in 1931, Murray called for "a spirit of cooperation" between management and workers. Ten years earlier the UMW had been the most powerful union in the AFL; now it was in disarray after several years of a depressed coal industry and a wave of rank and file pressure against John L. Lewis' leadership that included John Brophy's challenge campaign for the union presidency and the establishment of a dual union by militant Illinois miners in District 12. In line with Lewis' desire to make peace with the industry while controlling the movement of miners, Murray told the assembled group in Harlan County to go out and organize — but only organize. The union, he said, "did not intend to precipitate strikes."

But the miners had not come to Pineville to hear pleas for only organization. Certainly Jones did not expect to be told to undertake a task he had already accomplished. He wanted concrete evidence of the international's support for the miners' struggle. He knew that once the local organizing was discovered, men would be fired and a strike would become inevitable. With national support, the union might not be starved into submission. However, the national officials, bolstered by the large turnout at the Gaines Theater, left Kentucky feeling serenely in charge of the "rebirth's" orderly growth. The next two months would prove disappointing to both groups.

I.

"We wanted better conditions, and wanted checkweightmen, and pay for the coal wanted to spend it where we pleased." —William Hightower Harlan County, 1931

Harlan County's coal operators reacted swiftly to the surprisingly large turnout at Pineville. Their success — making profits in the Southern coal fields — depended on the low wages paid to workers. Consequently any movement toward organization must be crushed. The day after the Pineville meeting, 49 men and their families were evicted from their company-owned homes at Harlan Wallins Coal Company in Molu, Ky. Sixty more were evicted from the Black Star Coal Company at Verda and 200 families lost their homes at Black Mountain. All were evicted by company guards because they allegedly participated in Sunday's meeting.

In the next few days, more and more mine guards — known as "gun thugs" to miners — were hired and promptly deputized by Harlan County Sheriff John Henry Blair. In March alone, Blair swore in 26 new county deputies and 144 company employees, including the superintendent of Peabody's Black Mountain mine. Peabody's home office in Chicago also ordered the superintendent to institute the "yellow dog" contract system which required miners to promise they would not participate in any form of union activity. In a hundred other ways, from the blacklist to withholding credit at the company store, the mine operators tightened their hold on every aspect of county life. Most miners had no money to leave the area, and few found it easy to turn tail and run. The choices for the Black Mountain union had fast become quite limited: somehow they must stand and fight.

W. B. Jones, now secretary-treasurer of the Black Mountain local, knew he had enough strength to close down Peabody's operation — but that was all. Before they could finish recruiting in other mines on Clover Fork, the huge Pineville meeting had revealed the potential power of the organizing effort. Yet letters to Lewis from evicted and hungry miners received only the frustrating reply: "Under the laws governing the International union, there are no funds available for individual relief, and it's therefore impossible for me to assist you." Undeterred, Jones and his officers worked overtime in the next week to consolidate power at Black Mountain while reaching into other camps.

On March 9, Jones and his family were evicted from Black Mountain, and like many others, he moved to Evarts, one of the few towns in Harlan County not owned by the coal companies. As organizing continued, the town became a haven for union activity. Meetings that could no longer be held in the small, narrow hollows were moved to the schoolhouse yard in Evarts.

On Sunday, March 15, Jones was ready to make a show of power. Gathering on the school grounds in Evarts, 2700 miners and a few wives marched across the Clover Fork and down the Harlan road toward Verda. The march was peaceful since few would dare tangle with such a large group of armed men. The day ended with 300 Verda miners taking the union obligation. But the high point came before the march started when Jones announced the date the Black Mountain miners would walk off their jobs.

II.

"We were working and starving, so we might as well be striking and starving." — Tillman Cadle Townsend, Tenn., 1975

The first shift of the Black Mountain mines moved underground at 7:00 a.m. On Tuesday, March 17, the men on the first shift loaded their tools on the cars and followed them down the main entry on all fours. The miners then branched off to the rooms assigned to them for the day. Normally, by 9:00 the first cars loaded with coal moved back to the surface, and the men enjoyed a short rest before the empty cars returned.

But this Tuesday was different. The cars that appeared at 9:00 carried only the tools of the workers who were crawling back to the surface. By 9:30 Peabody's Black Mountain mine was closed down. Red Poore remembered the day well:

"March the 17th is the day we walked out over here....Arthur Scruggs was the boss over on this side, and I didn't have no use for him. We were brothers' children, but still he was the boss. He said, 'If you let this damn union grow, it's your fault.' I said, 'Shit, if I sit on my damn fanny and the other fellow sits on his, it won't go no damn where, don't I know that....I was raised a union man and so was you.'

"I said, This is it.' 'What do you mean, this is it.' And I said,'You just look at the next trip as it goes by here and you'll see whether we're coming out or not.' I sat there. The tram motor come by and every car had a kit of tools on it. I didn't even bring no tools out. I come out of there with a pick about that long and broke off. I was going to stick it tight in his chest, just as deep as I could stick it; that's the way I felt. 'God damn, you better let it go. You'll be out of work all over this damn county.' Well, I was, you see."

The miners knew that the momentary success at Peabody would be meaningless unless their organizing drive could command county-wide support, eventually closing down the other 50 mines at will. "The whole county, hell yeah," recalled Poore."You don't try to take a piece of the cake; you try to take it all."

Evarts became the focal point for a district wide effort. W. B. Jones opened a UMW office in a spare room in the house he rented in town. Miners up and down Clover Fork came to report on local activities, pay dues, or just get information. During the day, strikers sat around downtown Evarts and talked; at night, they attended regularly scheduled meetings and occasional mass rallies in the school yard. Eight armed men stood guard outside Jones' house to discourage any move by the company "thugs" who periodically passed through the town.

To facilitate the creation of new locals in the county, Jones developed his own group of 12 to 16 organizers who moved in pairs behind the scenes, working through leaders in the various non-union camps. "You had guys going everywhere," said Poore. "Finally they went down into Bell County. We're exactly like a damn octopus. We used to get into anything that opened." Avoiding the harassment of company guards was only part of the problem. The new union had to challenge directly the power of the coal operators by showing potential recruits how strong it was. To accomplish this goal, Jones decided on the tactic of highly-visible, yet completely legal, mass marches. Word spread along the Clover Fork, often through a network of relatives, as to the time of the march. Union members and their wives gathered in Evarts before starting up or down the road. Generally, the destination was a particular coal camp where new members received their obligation after a rally. At times, Harlan Town was the target, with marchers passing through coal camps all the way down Clover Fork before gathering at the county courthouse to hear speeches by Jones and others.

Thus, the marches served as a roving picket line that, while not breaking the law, demonstrated strength and built enthusiasm among the isolated camps. "Just keep moving, that's the idea," instructed Poore. "You ain't blocking nobody, you ain't interfering with a damned soul." To set up individual picket lines at each mine would have been ineffective and demoralizing. But the sight of 2000 miners marching behind Jones and his organizers riding in an open car with the American Flag, brought many men into the organization who, otherwise trapped in the loneliness of the company camp, would never have joined the rebel union.

In late March, another 107 men were evicted from Black Mountain. On March 24, some 1500 "keenly agitated" miners gathered around the Harlan courthouse to protest the evictions. A petition circulated by union leaders asked Kentucky Governor Flem Sampson to remove the county sheriff and judge who enforced the union-busting tactics. By mid-April 17,000 had signed the document and marches with as many as 2500 miners were common. Most of the time the marchers were armed. Rallies in front of the Harlan courthouse swelled to massive proportions, hitting 4000 by the end of April. Tensions were reaching the breaking point, and the opposing sides quickly drawn.

Faced with the same enemy, black and white miners in Harlan formed an integrated union. It was not, however, union policy to end discrimination in housing and public facilities. The racism instituted by the operators when they first brought blacks to the coal fields continued. Black union members took care of their own, with wayward strikers often receiving a "baptism" in the Clover Fork from black leaders.

But in union business, all members had a voice. Preacher C. G. Green, 69 years old and a 30-year union man from Alabama, was one of the regular black speakers at meetings in Harlan and Evarts. At one of these Harlan meetings, recalls Tillman Cadle, "Somebody asked Preacher Green how he thought a sheriff could be elected by the people and to be so closely tied up with the coal companies and do their bidding, the way John Henry Blair did. And the way he described it, he said, 'If you go down to the store and buy yourself a piece of meat and take it home, you can cook it anyway you want to. You can boil it or fry it or cook it anyway you please because it's your meat. You bought it....That's the way the Sheriff is with the coal companies; they bought him and he's their meat."

Miners' wives bore the strike's greatest hardships, but had the least control over the union movement. Women were not allowed to attend union meetings and could only participate through occasional marches. The union men viewed the movement "for workers only" and often did not tell their wives where they were going as they left the house late at night. Left at home, alienated from the union, women saw the organizing drive through the eyes of their hungry children. A Bell County woman recounts those days:

"Many of a day I've walked the floor and cried. I didn't know where the next meal was coming from. When I'd see any of my neighbors pass, I was afraid they'd speak to me and I'd bust out crying — every time I'd talk to anybody. I'd go back into the house and make sure they was gone before I'd show up again. I've seen the days when we didn't have a thing to eat, only just one thing, maybe bread or beans. But, I ain't ashamed of it."

Jones set up a relief committee that dealt with this critical problem. Men were sent on foraging missions all through eastern Kentucky, Tennessee, and as far south as Georgia. Wagons and trucks would not return to Evarts until they were filled with food and clothing. Within the locals not on strike, collections were taken up for those in Evarts. Despite the intensity of the relief work, many went hungry. By the end of April hungry miners began breaking into the Evarts A&P on a nightly basis.

Calls for help from the national union continued to fall on deaf ears:

My Dear Mr. Lewis:

Just a few lines to let you know the condition in Harlan County. We are getting along Fine with the Union men are Joining Fast and the Operators are Discharging thim as Fast as they Join and they are Starving Little Children and Hungry Good women are Bairforred and Hungry and they Cant Stand it Much Longer. Cant you help us Feed thim... if we can Just get something for Our Folks to Eat we will win but it Must come at Once Or I am afraid we will loose again and that means Hardship Heeped up Harder on our People.

III.

"These miners were all expecting Turnblazer, he was the district president, to come down, but he would never come down. It got so he'd send some little field representative there, mostly a guy named Bob Childers. He'd come and talk to these men and they kept asking where Turnblazer was. And one day he said that every time he came up there all he ever heard was, 'Where's Turnblazer, where's Turnblazer? So I'll tell you where he's at. He's exactly where Jesus was when they were all asking where Jesus was. When they found him, he was talking with the wise men.' Turnblazer was up in Frankfort making arrangements with William Sampson to send the troops in." — Tillman Cadle

"We are having a wonderful time." — William Turnblazer, 1931, Reporting on the walkout in the UMW Journal

From the beginning, the UMW had no intention to strike coal operations in eastern Kentucky or to help the insurgents led by Jones. Throughout March, Turnblazer and Dwyer continually tried to get the men back to work and publicly denied any involvement of the national organization in their struggle. Dwyer personally told the Governor, "I wasn't organizing and I wasn't even re-establishing the local unions at the camps." By early April, a conference was arranged between the US Department of Labor, the union and the operators. With problems mounting, the district officers were ready to deal. Dwyer wrote Lewis on April 10,

"Herbert Hoover he just now told me over the phone he is going to see Gov. Sampson, he told me the operators made a proposal... which was the operators said if we make a public statement that we had no campaign of organizing on and for us to keep out of Harlan County they the operators would put back to work as many of the discharged men as they could and he said that Turnblazer said if the operators would sign up a written statement to him promising to reinstate the men back to work we would go into Harlan County and that we have already made a public statement that we had no campaign of organizing on. And he said the operators refused to make any kind of an agreement with us...”

Eleven days later, after more marches and walkouts, Dwyer again told Lewis of a possible deal with the operators: "I said if the operators will give me a little consideration (I mean the organization) I will gladly help quiet the men.”

As the strike moved into late April and early May, the national union intensified its efforts to discourage organization. In response to a court order prohibiting 400 named union members from entering the coal camps, Turnblazer distributed a circular urging miners to follow the court's orders. The pleas for order were reiterated in the May 1 issue of the UMW Journal.

Indeed, order was the goal of both the national union and the Harlan County Coal Operators Association. Dependent on the same system of industrial mining, both union and mangagement inextricably tied their success to the economics of that system: a failing coal industry meant a failing coal union. The Black Mountain miners refused to accept such a principle of subservience. Consequently, the nature of the Harlan strike, a struggle uncorrupted by compromised institutions, with both leadership and membership in the working class, threatened the industry and the United Mine Workers. Reestablishing order, therefore, meant death to the Harlan organizing drive. The insurgents were on their own.

The level of frustration and violence steadily rose as meetings grew larger, more men walked out, families grew hungrier, and the hope for national support vanished. A mine guard at Black Mountain was wounded by a sniper's bullet; scabs were publicly whipped and beaten by union men; mine entries were dynamited. A mid-April Knoxville News-Sentinel headline warned, “Flare Up in Harlan Expected"; ten days later a machine gun battle broke out between miners and a posse of deputies. Houses were burned and stores looted. On May 1, Jones was forced to establish armed patrols to guard Evarts' businesses.

The daily routine of sitting and waiting on the streets of Evarts bred increased frustration, boredom and tension. "You could tell that there was something in the air," says Poore. "Evidently, it had to be — not knowing where the next damn meal was coming from, see...You'd see a bunch of 'em (company guards) coming, you know, cause you'd see them damn rifles. And when they got out, everyone of them always looked like they wore overalls and them pea jackets. 'Here come the goddamn thugs.' If they suspicioned something they'd get out and check people, see if they had guns on 'em, whoop heads. They done everything, buddy."

Early May found the Black Mountain local larger and better organized than ever. But it seethed with hopes and desires that seemed to move farther from reach as each hour dragged by.

IV.

"Hell yes, I've issued orders to shoot to kill. When ambushers fire on my men, they'll shoot back and shoot to kill. That's what we use guns for here." — Sheriff John Henry Blair, May 1, 1931

On Monday, May 5, the violence that had been growing in Harlan peaked when three guards and one miner were killed in a half hour battle just outside Evarts. At 9:30 that morning, three cars carrying nine Black Mountain mine guards passed through Evarts on the way to Verda to escort a new mine foreman to the Peabody camp. The union miners, having already seen the company trucks heading down the road two hours earlier, gathered around the Evarts depot and along the highway. A few hundred yards below the road took a bend to the right; a hill was to the right of the road and bottom river land was to the left. Just as the three cars made the turn a shot was fired and both sides opened up. After some 30 minutes of shooting, the fight ended leaving four men dead.

For the strike, the May 5 battle was an important turning point. The struggle now reached a stage Jones had feared throughout the last week in April. The outbreak of violence gave the operators an excuse to use the full power of the local and state governments. The UMW officials were put in the position of not only defending a strike, but, in the eyes of the nation, a murderous and lawless uprising— a step they would not take. Within two weeks, the inevitable results would be in: the strike would be broken.

The immediate effect of the battle was to increase the number of men on strike until only 900 men were working in the county. Eight or ten thousand belonged to the union. But two days after the shootout, 300 National Guard troops entered Harlan County and camped just outside Evarts. The troops were called in by Governor Sampson with the written approval of Turnblazer and Dwyer under an agreement that the Guard would disarm both miners and company guards. Within days it became apparent that the Turnblazer- Sampson agreement would not be fulfilled. Blair refused to disarm his deputies while the troops began to confiscate the miners' weapons. On May 12, pickets stopped a furniture truck moving a strike breaker into Black Mounatin only to have the soldiers escort the vehicle into the camp.

Local authorities, meanwhile, moved to eradicate the union leadership. On May 9, W.B. Jones was arrested for the May 5 killings. Hightower became the active leader in the movement and made a series of speeches in Harlan and Bell Counties to help rally the slowly faltering union. Hightower castigated the Governor for breaking his promise of equal justice under the troops saying he saw "no difference between working under the guns of 'tin hats' and working under the guns of the 'thug mine guards.'"

Within days, Hightower was also arrested for the May 5 killings. Eventually 43 miners were arrested on charges related to the battle, including the entire leadership of the union. Other arrests wiped out the leadership that filled this first void. Large groups of men returned to work. As tensions in the county subsided, the troops became bored and took to drinking binges and selling weapons to the miners.

The next step for the operator-UMW-government coalition was the ideological destruction of the movement. In mid-May Blair ordered a raid of Jones' house and came up with IWW literature. Reporters in the area believed the papers were planted by Blair, which could well be true since the IWW had been virtually defunct for over a decade. Furthermore the best known IWW member in the county turned out to be a paid informer for Sheriff Blair. Shortly after the raid, Blair denied miners the right of assembly and broke up a Harlan meeting with tear gas.

Governor Sampson complained that "several undesirable citizens from other states have taken up their abode at Evarts and are inciting and leading the trouble....Some are said to belong to those societies called 'Reds' and 'Communists,’ and are opposed to the regularly constituted authority and to law and order."

Meanwhile, the United Mine Workers' policy toward the striking miners did not change. Turnblazer publicly denounced the Governor for breaking their agreement regarding the troops; but privately the two met together with Harlan coal operators, and Turnblazer promised to abandon the field if some assurance was made to provide relief for the miners. For good measure, the May 15 issue of the Journal concluded, "if the coal operators had not allowed the IWW to get a foothold, there would have been no disturbances." In a separate editorial, the UMW officially signed out of the Harlan field.

V.

"I've been framed up and accused of being a Red when I did not understand what they meant. I never heard tell of a Communist until after I left Kentucky." — Aunt Molly Jackson, 1940s

Although the "Battle of Evarts" marked an end of the union movement in Harlan County, the exact opposite was projected by the media throughout the country. Radical organizations read the short, front-page articles on the killings and moved to assist the miners — and their own causes. Both the International Workers of the World and the Communist Party sent lawyers to assist the UMW lawyer in the Jones-Hightower trials. Confused, the local leaders first agreed to have the IWW's General Defense Council aid their defense, then switched to the CP's International Defense Council and back again. The misunderstanding and distrust shown by Jones and his co-defendants when dealing with the outside radical groups was to appear repeatedly in the next few months.

In hopes of destroying the faltering American Federation of Labor, the American Communist Party, under 1927 directives from Moscow, began to form a dual union structure. Under the governing body of the Trade Union Unity League, individual unions, such as the National Miners Union (NMU), started to actively oppose corresponding AFL unions. In its three years of existence before the May battle, the CP union had participated in organization attempts in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, and West Virginia. Only one of these movements, however, was in any way initiated by the NMU.

The NMU's entrance into Kentucky showed no exception to their tardy nature. With all the leaders of the large spring strike in jail and mines back in operation, the NMU sent in its first organizer, Dan Slinger, a dedicated veteran of the NMU's brief stay in Illinois. Using the name Brooks in Harlan, the middle-aged organizer spent long hours throughout July working secretly and through local contacts to form a NMU base in the county. By mid-July, Brooks had gathered 27 men, black and white, to go to a national NMU meeting in Pittsburgh to present the cause of the Kentucky miners to the national body.

After the July meeting, the NMU began to organize in earnest throughout the several southeastern Kentucky coal counties. CP organizers, fresh from the struggles at Gastonia, Illinois, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, soon entered Harlan and Bell counties. Brooks and other male organizers worked to build locals at the mines. Caroline Drew and other women field workers set up women's auxiliaries alongside the miner's unions. Activities were coordinated through a central strike committee of purely local miners, black and white, and women. The NMU leaders served as advisers to this group. Soup kitchens opened throughout a number of counties and became focal points for the organizing efforts. Meetings were held in secret and under armed guard.

By late summer the NMU found that the poorer and more destitute miners on Straight Creek in Bell County were more willing to join the new union. Most of these men were out of work. For a number of weeks in the late summer and early fall of 1931, the NMU led marches down both forks of Straight Creek and on into Pineville. Scattered picket lines appeared before a few of the small number of working mines in the area, but no operation was closed for more than a few days. By October, the NMU's strength in the area began to fail. Soup kitchens were dynamited, men and women were arrested on various conspiracy charges, organizers were beaten and sent out of the state, soup kitchen operators were murdered, and the overwhelming need for food and clothing brought many union members back to work. In hopes that national publicity would aid their faltering efforts, the Communist Party arranged for Theodore Dreiser and seven other noted writers to investigate the conditions in the Kentucky coal fields. This November, 1931, excursion by Dreiser's entourage marked the beginning of a flood of writers, professors, students, intellectuals, and theologians to the Harlan-Bell area that lasted well into 1932. It boosted media coverage considerably, fixing "Bloody Harlan" in the nation's memory — but the attention did little for the miners' beleaguered position in the fall of 1931.

Meanwhile, Brooks believed that a strike had to be called immediately, and he wrote the New York office asking for permission to set a strike date. Those making strategy for the strike did not think the ground work was properly laid. They refused Brook's request and withdrew the organizer from the field. Another chief field worker was not sent in for another two months. When a strike was finally called for January 1, the union had lost all semblance of its earlier small support. The strike failed and the NMU was essentially wiped out with the January 4 arrest of nine organizers and the well-publicized February 10 killing of the Young Communist League organizer Harry Simms. The strike was not officially called off, however, until March, 1932.

The primary reasons for the NMU's failure in Harlan were basic and later recognized by the Communist Party. The union's base was composed of four to five thousand men and women who were either out of work or blacklisted and thus powerless to affect the industry through strikes or walkouts. The structure of the Party also hindered a successful movement. Strategy decisions were made outside the state, not by organizers in contact with the miners.

Perhaps the largest failure of the NMU was its misunderstanding of the miners' reactions to the union's Communist Party affiliation. Few knew the complexities of Marxist ideology, but most believed that the communist label did not fit their way of living. Many objected to the anti-religious stance of the Party while others differed with various perceived aspects of the name. Once the fact was discovered, most everyone had the same reaction: they quit the union. One miner who helped organize soup kitchens until the early fall, remembers when he went to Pennsylvania to help distribute some NMU literature. "I was sitting underneath this cucumber tree, reading this literature and said, 'Uh-oh, what have I gotten myself into.'"

To the Party's credit, a number of men and women, notably Aunt Molly Jackson, Tillman Cadle and Jim Garland, were inspired by the NMU and continued to be involved in worker's struggles throughout the country. These people, however, were only discovered by the Party; all were "revolutionized” by the experience of living in a Kentucky coal camp. Most of those who joined the NMU in 1931 now bow their heads or avert their eyes when asked about the Communists. Men talk of "grabbing at straws" in late 1931, looking for any groups that could and would help. Some even look away and say no group called the National Miners Union ever entered Kentucky.

VI.

W.B. Jones, William Hightower, "Red" Poore, and five others were convicted of conspiracy to murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. Despite a 1938 investigation by the U.S. Attorney General's office, urging Kentucky Governor "Happy" Chandler that "justice would be served by an exercise of executive clemency," Jones, Poore, and two others remained in jail. In 1941, labor leaders in Kentucky, knowing that Lt. Governor Rodes Myers would grant pardons to the miners, contacted Eleanor Roosevelt and Senator Alben Barkley in hopes of securing an invitation from the President for Kentucky Governor Keen Johnson. Johnson was reluctant to turn over the power of the Governor's office to Myers, and in fact, had turned down two previous presidential requests. In December, however, the Governor left the state and Myers reduced the sentences of the unionists and granted immediate parole. The miners left the prison on Christmas Eve, 1941.

Tags

Bill Bishop

Lexington Herald-Leader (1994)

Bill Bishop is on the staff of the Mountain Eagle in Whitesburg, Kentucky. (1976)