1872: Visitor From Hell

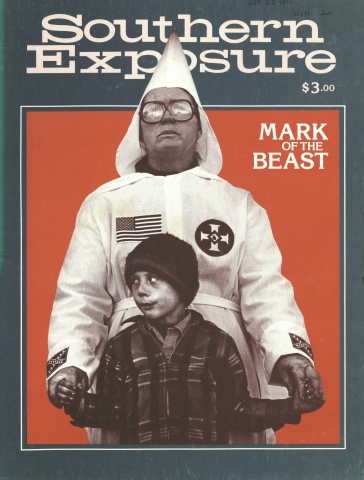

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

They had gowns on just like your overcoat, that came down to the toes, and some would be red and some black, like a lady’s dress, only open before. The hats were made of paper, and about 18 inches long, and at the top about as thick as your ankle; and down around the eyes it was bound around like horse-covers, and on the mouth there was hair of some description, I don’t know what. It looked like a mustache, coming down to the breast, and you couldn’t see none of the face, nor nothing; you couldn’t see a thing of them. Some of them had horns about as long as my finger, and made black.

They said they came from hell; that they died at Shiloh fight and Bull Run.

They said they wanted [my horse] for a charger to ride into hell. He was a mighty fine charger. They said they came from hell, and wanted to ride him back to hell. They said they had couriers come from hell nine times a day, and they wanted that horse to tote them.

– Joseph Gill

Huntsville, Alabama

The above testimony captures the ghoulish terrorism that typified the early days of the Ku Klux Klan. With brutal insistence, the post-Civil War Klan terrorized the black community, running off political leaders and maintaining a climate of fear throughout the South.

In 1871, a congressional committee convened site hearings on the Klan’s activities in the Southern states. Published in 1872 under the title “Testimony Taken By the Joint Select Committee to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States,” the resulting committee report contains the stories of hundreds of individuals ’ experiences with the Klan. The stories below, all taken from the hearings in South Carolina and Alabama, reveal the cowardly forms of terrorism the Klan pursued and the total absence of effective attempts to control its violence.

Most of the early Klan’s efforts centered around driving out the reconstruction governments of the post-war period. The “radicals” of the Union League and other groups had instituted progressive changes in government and defied the white supremacists. Klan leaders and their cohorts often tried to buy off, scare off or murder the leaders of the black community. James Alston of Tuskegee, Alabama, recounts one assassination attempt:

I was elected a representative of Macon County. I was threatened every day. I was threatened by a good many white persons, and I was threatened by colored persons that they had appointed. I was offered, by Mr. Robert Johnson, $3,000 to use my influence in the county against my constituency.

I told him that Jesus Christ was betrayed for 30 pieces of silver, only one to the thousand he offered me, that he wanted me to do the like; but that I wouldn’t do it for $3,000 or to save my life; that I held my life more dear to me than anybody else, but I wouldn’t betray my people to save my life.

I was shot, I reckon, about 16 months ago. My shutters were closed, and I was in the house, sitting on the side of my bed, and they fired through the windows; I didn’t see the men at the time. Two hundred and sixty-five shots were counted outside in the weather-boarding of my house the next day, and 60, as near as we could count, passed through the window, and five through the head-board of the bed I was sitting on and two through the pillow my head would have laid on, and four in the foot-roll of my bed, and two in my body. I now have buck and ball that injures me a good deal, and I think it will be for life; and my wife [and one of my children] have been injured a good deal. I have been in this place about 16 months, not allowed to go to my own property, and I am suffering. My horses, one of them, is killed. Taken away from me and the buggy cut up. My house and lot is there, and I am not allowed to go near the county.

As South Carolinian Harriett Simril relates, the Klan also took out its fury on women:

The first time they came, my old man was at home. They hollered out, “Open the door,” and he got up and opened the door. They told him to come out, and he came out. These two men that came in, they came in and struck matches to a pine stick and looked about to see if they could see anything. They never said anything, and these young men walked up and they took my old man out after so long; and they wanted him to join this democratic ticket; and after they went a piece above the house and hit him about five cuts with cowhide. He told them he would rather quit all politics, if that was the way they was going to do him.

They came back after the first time on Sunday night after my old man again, and this second time the crowd was bigger. They called for him, and I told them he wasn’t here; then they argued me down, and they told me he was here. I told them no, sir, he wasn’t here. They asked me where was my old man? I told them I couldn’t tell; when he went away he didn’t tell me where he was going. They searched about in the house a long time, and stayed with me an hour that time; searched about a long time, and made me make up a light; and after I got the light made up, then they began to search again.

They were spitting in my face and throwing dirt in my eyes; and when they made me blind they bursted open my cupboard. I had five pies in my cupboard, and they eat all my pies up, and then they took two pieces of meat; then they made me blow up the light again, cursing me; and after awhile they took me out of doors and told me all they wanted was my old man to join the democratic ticket; if he joined the democratic ticket they would have no more to do with him; and after they had got me out of doors, they dragged me into the big road, and they ravished me out there.

The post-war years also saw many acts of violence against blacks that weren Y necessarily Klan-related. Instead, they seemed more a holdover of the plantation mentality. John Childers of Sumter County, Alabama, told of the death of his daughter:

My wife hired [my daughter] out to a man while I was gone. She was hired out as a nurse to see to the baby; she had taken the baby out in the front yard among a parcel of arbor vitae; and, being out there, the baby and she together, she was neglectful, so as to leave the baby’s cap out where it was not in place when the mother of the child called for the cap, and it could not be found. That is what she told me when I came home that she was whipped for.

[When I came home] she was sitting in the door, and I asked her how it come she was not playing with the rest of the children. She says, “Papa, I’m so sore I can’t play.”

I say, “What’s the matter with you?”

She says, “Mr. Jones has beat me near to death.”

I says, “He did?”

She says, “Yes.” She pulled up her coat here and showed me. “Look here, papa, where he cut me,” and there were great gashes on her thighs, as long as my finger. [Later] I commenced examining her, and I found bruised places all over her body, up here, you know [indicating the waist]. She died seven days after I got home. I buried her with scars that long: a finger-length.

But if a victim tried to prosecute, he soon found the hand of the Invisible Empire at work. Said Childers: Mr. Jones, who had employed her from my wife, he was the one that did it. I aimed to prosecute him at the last gone court, but the witnesses, by some means or other, was run away. I don’t know; I could not tell how they got them out of the way. There was no case made of them.

The Klan had a vise-like grip on the entire legal system and made a mockery of the judicial process. William K. Adams, a former member of a South Carolina Klan chapter known, ironically, as the Black Panthers, explained the code that dictated a Klansman’s activities.

He is bound to do all he can. Suppose a case was got up - a murder case. I belonged to the party. Well, if they were to arrest a man, and he was charged with this murder, and I was to be called on as a witness to prove that he was with me that night, although I had not seen him at all, I would have to go and swear that he was with me that night, although I had not seen him at all, I would have to go and swear that he was there that night with me; that’s the plan of operations. Several cases have been got up here on suspicion of Ku Klux Klanism, but they are always proved out, because they can produce abundant proof; that is the principle of the party. They are bound to clear each other at the risk of their lives.

[A juror] has to do all he can for the prisoner; it makes no difference what capacity he is in, he is bound to do all he can for him.

I say if I am arrested or charged with Ku Kluxing a man, I go to a courthouse; I subpoena two or three witnesses; I can go there and take my lawyer to question these men and ask them where I was that night, and I can make them turn around and prove that I was 20 miles from the scene of operations that night. That is the plan of proof — that is the only thing, by undeniable evidence, to throw the prosecution.

With the odds overwhelmingly against them, politically active blacks were forced to flee their homes by the hundreds. Even the witnesses at the congressional hearings feared for their lives after testifying against the Klan. Said John Childers:

Well, gentlemen, I am delicate in expressing myself. I feel myself in great risk doing these things. I have no support in the State of Alabama. I am a citizen here, bred and born; and have been here 42 years. If I report these things, I can’t stay at home. I am in a tight place where I am, and I wish to give you gentlemen all the satisfaction I can but, in the same time, I must be particular in saving myself, because it is just as well to be in one gunboat as another.

In the face of such violent intimidation and weak federal support, blacks soon lost the progressive gains they had made following the Civil War. Reconstruction governments crumbled, and white supremacy reigned again. With this accomplished, the Klan slipped into the background, leaving behind a climate offear.

But even the strongest efforts of the Ku Klux Klan could not dampen the determination of many blacks to continue struggling for equal treatment. In fact, the words of many witnesses foreshadowed the power and commitment of the civil-rights movement almost a hundred years later. Concludes James Alston:

But I will go back there when I have the authority to carry that county republican; whenever I am protected by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments as a man amongst men, I am willing to go back any day, if I have the authority to do as Mr. Colfax told me to do when I was in Washington last. I was in a convention, sir. I was one of five men that went up to Washington City when one hundred white men went, and I am the only man that is living. Every one is killed or dead that went there to the inauguration of Grant. Mr. Abercrombie said I should not live, but God Almighty said I should, and I am living.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.