Teaching Educational TV a lesson!

John Northrop

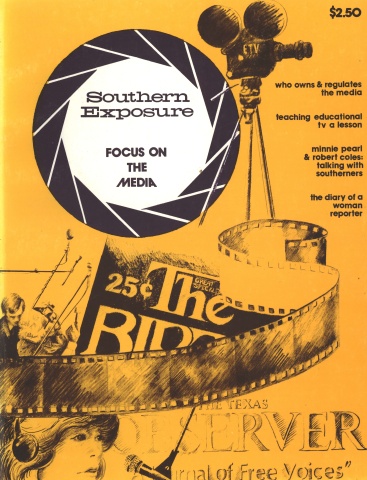

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

Scott Carpenter perches atop the director's stool in the control room of the Birmingham public schools educational television studio, his eyes darting across an array of monitors overhead. "Bring up the music," says Carpenter, and a funky, syncopated concoction of brass and piano floods the room. "Roll credits, Chuck. That's it. Give me a two-take, One."

It's the regular Tuesday afternoon taping session for the Alabama Educational Television Network program, "Youth Speaks Out." Through a massive plate glass window to his left, Carpenter can see Birmingham News assistant managing editor Jim Jacobson enthroned at the center of a studio set, four well-scrubbed high school students surrounding him like attendant vassals.

The music —which sounds like the background for an early Sixties police show —fades out, and onto the main monitor pops the image of the one black student on this week's program. "Today I'd like to discuss the recession in the United States," she says, and disappears.

Another student flashes onto the tube. "I'd like to discuss the possibility of Alabama losing its ETV rights," says the boy. A laugh ripples across the control room. "You tell 'em buddy!" says the video man. "You know," he says to another worker, "I think I'm going to like that kid."

Later in the program, the boy wins more control room applause when he launches into the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for "exercising a little too much power" by threatening "to completely do away with the state's right to broadcast."

In fact, there is virtually no chance of the FCC doing away with educational broadcasting in Alabama, although the current licensee, Alabama Educational Television Commission, may lose its privilege to hold the ETV frequency. Unfortunately, the young Birmingham lad is not alone in his misapprehension of an ongoing broadcast license controversy which already has led to some changes in Alabama ETV.

The hullabaloo erupted last September 19 when an FCC source leaked word to the New York Times that the Commission had just voted 4-2, with one abstention, to revoke the Alabama Educational Television Commission's nine station licenses because of racial discrimination in hiring and programming during the AETC's 1967-69 license period. As the story trickled south via wire services and a few telephone calls from fancy Washington law offices, AETC officials and other concerned individuals tailspinned into panic that after 20 years the jig might be up for the nation's first state ETV network.

As publicity gathered momentum, newspapers printed letters from educators and other citizens denouncing the FCC action. In Washington, a dinner for the state's congressional delegations, hosted by Alabama's junior U.S. Senator Jim Allen, led to an announcement of unanimous support for the AETC. Despite the pressure from such distinguished individuals, the FCC released on January 8, 1975, its formal opinion and an official 4-2 vote denying the license renewal of AETC based on a series of license challenges and complaints stretching back five years.

I.

A central character in the still unfolding ETV melodrama is Raymond Hurlbert, the first AETC chairman and general manager of the ETV network for nearly 20 years. Hurlbert is a tough, "good ole boy," with connections and a wall-full of plaques and messages of appreciation from governors and other government and civic leaders. It is Hurlbert, many believe, who is directly responsible for the network's survival — and some of its problems — since its humble birth in the 1953 Alabama legislature.

"Ray was hard-headed and strong, very strong," said a former AETC member. "We had run-ins when it came to programming, but in the area of management there wasn't anything he didn't know about. He was a genius at getting free equipment and supplies. He'd go to a supplier and say, 'Look, we buy a lot of things: if you hear of somebody throwing away a junk transmitter, let me know." In Hurlbert's words, all you need when raising cattle are "a few scrubs and one thoroughbred bull."

Now 72 years old, the "thoroughbred bull" has retired from his AETC post and chuckles about the early days of Alabama Educational broadcasting.

"We put the system together with chewing gum, bailing wire, and spit," says Hurlbert, lounging on a plush sofa in his suburban home near Birmingham. "It began with one or two hours of programming per week; now there are 16-18 hours every day. We have eight broadcast stations, another under construction, and 2,000 miles of microwave relay equipment; it's one of the largest ETV systems in the country."

Gov. Gordon Persons, a former radio broadcaster, appointed Hurlbert to the AETC, which is ultimately responsible for state ETV activities; at that time —summer, 1953 — Hurlbert was a Birmingham school principal. Persons stretched long fingers into state dock board funds to pull out $500,000 for the fledgling network's first two years' operations, initiating minor friction between Hurlbert and docks officials which continued for several years.

According to Hurlbert, the AETC decided early to maintain separate broadcast facilities and production centers; transmitters would be located to reach as many viewers as possible, while the production studios would be placed in educational institutions or other areas where resources could be gathered easily. It was decided most production centers would operate autonomously as independent contractors with the AETC. A state school board coordinator would determine certain in-school instructional policies while the AETC and its staff would coordinate production and set general programming policies. Hurlbert neglects to say, however, that the development of AETC's coverage areas in Alabama typified discrimination through neglect. The one portion of the state where educational broadcasting could not be received contained seven of the nine counties where blacks outnumbered whites.

The first broadcast tower was erected atop Mt. Cheha, near Talladega, and the state's first ETV broadcast came in early 1955. Rudy Bretz, a former CBS production man imported to teach inexperienced Alabamians something about television, plucked a guitar and sang folk songs. As broadcast stations were built, production centers opened in the Birmingham and Huntsville public schools and at the University of Alabama, Auburn University and the University of Montevallo. The only production center not affiliated with an educational institution was to be in Montgomery, in Humbert's words, "to be a voice out of state government."

"Representatives from Japan, Scandinavia, Germany — all over — came to look at the system," says Hurlbert. Even the ETV system in the islands of American Samoa felt the Alabama touch when an Auburn studio engineer traveled to the South Pacific to share his expertise. It would be simplistic to suggest that mankind can trace its ETV roots to the Alabama blackbelt, but the state system certainly had an important impact.

II.

Hurlbert bristles under charges of racial discrimination, claiming a long interest in making things better for Alabama blacks. But change comes slowly, Hurlbert argues, and people "who bang their heads on the wall can undo 20 years' hard work."

According to FCC records, the current dispute began in 1969, when the AETC transferred its National Educational Network (NET) affiliation from the University of Alabama production center in Tuscaloosa to AETC offices in Birmingham: this meant that national broadcasting — previously channeled through UA for later state network broadcasting — now would come under direct AETC control. AETC claims that the re-routing was performed for purely technical reasons proved unconvincing to the University. UA officials fired letters to the FCC complaining that the AETC had censored such black NET programs as "Black Journal," ' "Soul," and "On Being Black." A petition was filed, signed by 60 people, including the Civil Liberties Union's director Steve Suitts, then an American Studies student at the University. AETC contended, in part, that the programs had been kept off the air because of “obscene language"; AETC officials claimed such words as "screw," "bullshit" and "black ass" were unacceptable for public consumption, though AETC documents show that such words as "bastard" and "frigging" were considered in a "decent context" in the BBC production, "The Battle of Culloden."

Other letters complaining of AETC censorship arrived at the FCC. Rev. Eugene Farrell, a Birmingham Catholic priest who also helped force the integration of a formerly white-only Birmingham cemetery with the burial of a black Vietnam war veteran, wrote to a well-known friend of the media, then Vice President Spiro Agnew. (When Farrell's bishop learned that AETC officials had discussed the priest's critical letter, he challenged Farrell's right to question AETC programming practices. Farrell subsequently was transferred to a New Jersey diocese.)

In June, 1970, complaints notwithstanding, the FCC voted to renew AETC broadcast licenses, apparently leaving questions of "taste" to AETC discretion. Within a month Suitts, Farrell and a black UA student named Linda Edwards filed a request for reconsideration and called fora license hearing. They said that less than three percent of AETC programming involved black adults and that out of a commission staff of approximately 50 there were only two blacks —a janitor and a part-time clerical worker.

Not until early 1972, after gathering information from both sides in the dispute, did the FCC decide to schedule a hearing for later that year in, of all places, Birmingham Bankruptcy Court. An FCC judge flew out of the Washington snow to host the chilly confrontation; after hearing the evidence, he packed north again, having initially decided there had been discrimination, but without malice.

Last September, in Washington, the FCC heard oral arguments in the case and at that time voted not to take the staff judge's advice to renew the licenses; the Times story appeared the day after the hearing, reporting that "experienced communications lawyers" claimed "this was the first time that complaints from citizens about the performance of a television station had led the commission to decline to renew a station's license." The irony of it all—that the case involved the first state ETV network in the nation —went unnoted.

III.

With Farrell now gone north and Linda Edwards practicing speech therapy in South America, Steve Suitts is the last of the original plaintiffs left in Alabama. A lanky Winston County country boy, the state's first CLU executive director peers out with shy, blinking eyes and speaks gently with a nasal twang. One CLU member remarks that Suitts is "a good guy" and "smart," but "he doesn't come off well on television."

As Suitts himself admits, he doesn't do well in court rooms either. In 1972, for example, he was thrown out of Alabama's Supreme Court for refusing to rise when the venerable Justices entered the Court.

"I was sitting there waiting for a particular case to come up," says Suitts, "when I overheard a discussion between opposing lawyers on another case. 'I thought you'd stopped taking niggah clients,' said the prosecutor. 'Yeah,' said the defense attorney, 'but they pay pretty well when you get their welfare checks.' This was a serious discussion, right there in the open, in the Supreme Court of Alabama. I decided it would be ridiculous to rise if this were the dignity of court."

Obviously, such dramatics can be of questionable value in many circumstances, but the implication is clear: within Steve Suitts' soft, mild-mannered exterior lurks the bane of many a well-lubricated organization — a Man of Principle.

"I'm pretty morally certain that if we were given the choice of having ETV not fully integrated, or no ETV at all, I'd choose the latter," says Suitts.

Suitts' involvement within the Civil Liberties Union began at the University of Alabama, which he left without a diploma because he believed he "could learn more elsewhere." He got hooked on legal work in the summer of 1970, following campus disturbances that spring which led to the arrest of 26 students. As a CLU investigator, Suitts helped uncover evidence that the FBI had installed an agent provocateur on campus to help stir up trouble. While assisting defense attorneys during court proceedings later that year in Tuscaloosa, Suitts was thrown out of court the first time.

Suitts eventually politicked with state CLU board members and managed to create the executive director post for himself in 1972. At first the pay was $75 per month, with an old Dodge for an office. Now the Alabama Civil Liberties Union has more than 700 members, with two law firms on retainer and 30 attorneys across the state volunteering their services. Suitts, of course, is not an attorney, though some in the press for one reason or another insist on referring to him as such.

Suitts dismisses some of his critics in the ETV situation as hardly being concerned with equitable broadcasting. "A lot of them are worried they won't have 'Sesame Street' on Saturday mornings to keep the kids quiet," he says. Other critics say that before the FCC was pulled into the case Suitts should have tried to bargain with AETC officials, or, failing that, with Gov. George Wallace. ("Whatever George wants, George gets," claims one former AETC member.) Suitts answers simply that there were attempts to negotiate with the AETC, but "we were looked upon with not much respect. You would have thought we were asking them to negotiate with terrorists."

Now, Suitts figures, the high cards have changed hands. "With the FCC announcement that the AETC's licenses have been revoked, the AETC of course still has the opportunity to apply for new licenses," says Suitts. "But the burden will be with the potential licensee to prove that he will meet public interest requirements; that means that the AETC will have to bear responsibility for its past acts."

Suitts smiles. "The question is," he says, "how much will the AETC be willing to do to make sure those license applications are not contested by the CLU of Alabama?"

Suitts acknowledges there have been improvements in programming and hiring in recent years but points to needed improvements — like an increase in AETC black employment from today's 9 percent to 20 percent.

Suitts has found little support in some quarters of the media. Raymond Hurlbert says Birmingham News managing editor John Bloomer told him Suitts is "one man against 3 million citizens." Suitts seems undisturbed. "If John Bloomer were writing editorials in 1789," he says, "we never would have had the First Amendment."

The largest and perhaps most influential paper in the state, the News has long supported ETV through the "Youth Speaks Out" program and in other ways, Hurlbert says. In fact, according to Hurlbert, even the state's commercial broadcast media support the AETC —perhaps because ETV provides a training ground for engineers and technicians who then are ready to accept higher paying positions in the commercial sector. At least one large Birmingham broadcast station no doubt has been interested in the outcome of the AETC license dispute; WAPI, once an educational station but now, like the News, part of the Newhouse commercial media chain, is itself the subject of a discrimination complaint before the FCC.

IV.

Robert Dod, the man who became ETV general manager when Hurlbert retired, has the look of someone a trifle disturbed by an uncertain world. Like Hurlbert, Dod is a Rotarian, and the wall behind his desk is adorned with a solitary fixture— a framed reproduction of the Rotary "Four-way Test of the Things. We Think, Say or Do." The first test reads, Is it the TRUTH?

"Yes, I'd say there have been transgressions in the past," says Dod, knitting his fingers, "and I guess the license challenge helped bring change. But there has been change. The AETC has 53 employees: there is a black part-time secretary and six full-time blacks: a traffic engineer, the director of the AETC tape delay center, the chief engineer in the Montgomery studio, a transmitter engineer, a tape playback engineer and a janitor."

In addition, Dod says, since the challenge was filed there has been a survey to determine the black community's ETV needs. The state network's seventh production center has been organized at the predominantly black Alabama A&M University in Normal, and Dod says the center gets AETC funds "in proportion to other production centers." The Alabama Center for Higher Education (ACHE), a coalition of black colleges, is producing a series of black-oriented programs in various production centers. Dr. Harold Stinson, the black president of Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, has been appointed by Gov. Wallace to the AETC.

Since the AETC has never seen fit to indulge in extensive audience surveys, no one has any firm idea about who feels what or how strongly about ETV. Some individuals, however, are taking surprising stands in the present license situation. Birmingham newsman Bob Harper —a former AETC member who remembers dropping in on broadcast facilities in ETV's earlier days to

discover that workers were out fishing —did his best to roast Suitts during a CLU press conference following the September FCC vote, but later came out with what Suitts interpreted as editorials supporting the CLU position. On the other hand, long-time civil rights attorney and former FCC member Clifford J. Durr finds himself in disagreement with Suitts on some points. "If programming is any indication, some good people have found a way into the AETC organization," says Durr. "It would be a great tragedy to lose ETV in this state."

At 75, Durr is now retired, living near the tiny Elmore County town of Wetumpka. His home, overrun with stray dogs who have "taken up" with the Durrs over the years, is a rambling ranch house built with weekend labor on land bought in the 1870's by Durr's paternal grandfather, a captain in the first Confederate regiment from Montgomery. "Grandpa was against secession," says Durr, "but when the war came he joined up right away to keep from being called a coward."

"What bothers me about the ETV situation," says Durr, "is that the FCC is loaded now with Nixon appointees: I'm afraid they might take advantage of a 'civil rights' position to do away with something the Nixon crowd has never cared for —public broadcasting.

"Also, I've heard that George Wallace might try to break up the network." Wallace spokespeople seem genuinely surprised by that piece of information. Wallace, they insist, has supported the AETC for years and definitely does not want the system to end.

Besides, Wallace and other state politicians regularly receive valuable publicity through AETC coverage of official government events across the state. On balance, Wallace is expected to stay clear of the ETV controversy, so as not to complicate other involvements.

As for the FCC's intentions, the Wallace people have their own ideas. "I think it's politics," offers one spokesman. "The FCC decision seems to have come from a desire to embarrass the State of

Alabama and the Governor." Yes, says the spokesman, the decision could have something to do with the Governor's presidential aspirations.

V.

In its decision to deny the AETC license the FCC wrote, "We have found that AETC excluded blacks from the decision-making process, that it did not take the trouble to inform itself of the needs and interests of a minority group consisting of 30 percent of the population of the State of Alabama, and that, as a result, it virtually ignored the programming needs and interests of that minority group. A finding that it made reasonable efforts to ascertain and to deal with the problems of the black minority in Alabama cannot reasonably be made. We find that AETC failed to sustain its burden of showing that it served the needs of all of Alabama's citizens."

Alabama Senator Jim Allen, adroit tactician of divisive swill, was quick to label the ruling as a "slap in the face" and "proof of a malicious intent on the part of that small vengeful group who demanded that the FCC punish the AETV system despite the fact that the faults they had pointed to have been corrected." What many Alabamians have never understood throughout the entire FCC proceeding is that the license period involved was for the years 1967-1969 and that the improvements made in AETC programming and hiring practices in the years since 1969 were mainly due to the persistent presence of petitioner Suitts.

What happens now? The January 8, 1975, FCC decision recognized that "improvements under taken by AETC demonstrate that it has the capacity to change its ways and therefore that, despite its past misconduct, AETC possesses the requisite character qualifications to be a Commission licensee." Though it is conceivable that the AETC might appeal the FCC ruling in a federal court, the expense, delay, and uncertainty of outcome seem to make such a course unlikely. General manager Dod has said he feels sure the AETC will reapply for a license. No one realistically expects ETV to end in Alabama. "Folks might pick up their pitch forks and grubbing hoes if anybody tried to pull that," says one ETV employee. For now, the FCC has granted the AETC interim authority to continue operating the system's eight stations. There is little likelihood that any other organization will seek the ETV license, or that the FCC will ultimately deny a new application from the AETC. But some additional concessions, such as the appointment of a black assistant manager, may be demanded by Suitts before the matter is laid to rest.

Steve Suitts' involvement with Alabama media has grown from the original ETV petition to include coordinating challenges of more than 20 radio and television stations, participating in rulemaking proceedings before the FCC and Congressional committees, and creating the Alabama Media Project —a non-profit group which is working to develop public radio, cable TV access, and more participation by citizens in all the state's media. Testifying before the Senate Subcommittee on Communications, Suitts commented upon the AETC dispute but spoke as well of larger issues of broadcast responsibility: "What results have occurred in this case at present and may occur in the future can be credited not to the FCC as a regulatory agency and not even to the individuals who initiated the petitions to deny. Instead, the credit for what good has been done lies with a system of citizen participation which allows local people to address local situations based upon standards which all broadcasters should be expected to meet."

(The final section of this article was written by Allen Tullos after the FCC January 8th announcement, since John had left the country.)

Tags

John Northrop, Jr.

John Northrop, Jr., formerly of the Birmingham News, and the Birmingham Reporter, now works in American Samoa. (1975)

Allen Tullos

Allen Tullos, a native Alabamian, is currently in the American Studies graduate program at Yale University. (1978)

Allen Tullos, special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure, is a native Alabamian. He is currently in the American Studies graduate program at Yale University. (1977)

Allen Tullos, a native Alabamian, is a graduate student in folklore at the University of North Carolina. (1976)