When will North Carolina get fair election districts?

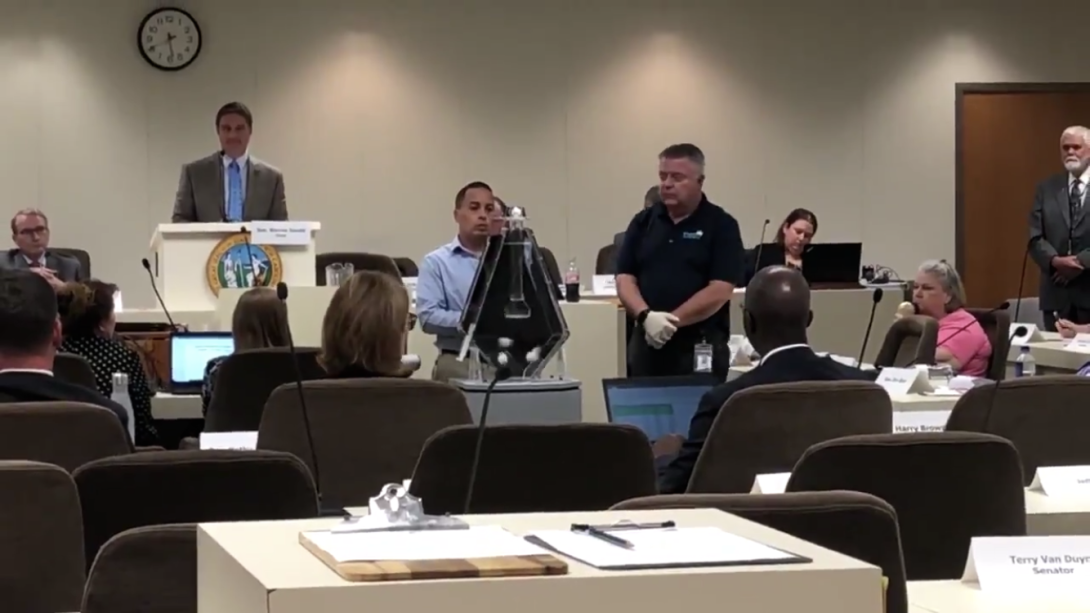

N.C. Education Lottery employees operate a lottery machine that state legislators used to choose a baseline map to redraw unfair election districts, as required by a court order, on Sept. 10. (Image is a still from video by Lekha Shupeck.)

After eight years of redistricting and litigation, North Carolina voters will choose their state legislators in new election districts in 2020.

The boundaries of the current districts are so skewed that Republican candidates in last year's election got less than half the votes across the state, but the GOP still won 54 percent of the seats in the state legislature.

Last week, a state court ruled that those election districts violate the state constitution and ordered legislators to draw fair maps — within two weeks — at public hearings. The court also began drawing its own maps that it would use "should the General Assembly fail to enact lawful Remedial Maps" before Sept. 18.

Republican leaders kicked off the process on Sept. 9 by defending the practice of partisan gerrymandering. Sen. Paul Newton, chair of the redistricting and elections committee, said that drawing maps to benefit one political party was "never considered wrong or evil" before last week's ruling. In fact, Newton said voters expected legislators to "leverage" the redistricting process.

"Never before has a legislature been ordered not to consider partisanship in drawing maps," he said. "The rules of the road have now changed." Newton emphasized that legislators would draw the maps without using partisan political data, as the court had ordered.

Citing the two-week timeline, Republican legislators decided not to draw their own map but instead start with one of 1,000 maps generated by Jowei Chen, an expert witness for the plaintiff, Common Cause North Carolina. Chen's analysis sought to demonstrate the extent of partisan gerrymandering by comparing the current maps to other alternatives.

The court's order laid out eight criteria for the legislators to consider, including equal population, fewer split voting precincts, and respecting the boundaries of cities and counties. In the Senate, legislators decided to choose one of the five maps that scored the highest on these three criteria in Chen's analysis.

In essence, legislators are choosing from among the most compact of Chen's maps. But the problem the court ordered them to solve isn't a lack of compactness; it's the unfair partisan skewing of the districts. The court ordered legislators only to "make reasonable efforts" to improve the districts' compactness.

Sam Wang, who runs the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, said in an interview that more compact maps don't always favor one party or the other, but on average they "tend to favor Republicans." That's partly because Democrats are concentrated in cities, Wang said, but also because "city voters are more monolithic in their preferences than rural voters." A 1998 study found that compactness mandates "are likely to have distinctly partisan effects" in many states.

When legislators were debating whether to emphasize compactness, Wang noted that Chen also scored his 1,000 maps on whether they benefited one party or the other. "The committee should start with a plan in the middle of the partisan range of outcomes," he said. "That would be better than most compact."

On Sept. 10, state senators chose one of Chen's five most compact maps at random using a lottery ball machine. The Senate released its map, and Wang's initial analysis found that "on average, these maps are still biased toward Republicans."

'Elections shall be free'

In its ruling, the state court in Wake County held that the legislature's election districts were unconstitutional because they lock Republicans into power and leave almost no chance for Democrats to take control in the closely divided state. The districts at issue were drawn in 2017 to correct Republican lawmakers' unconstitutional racial gerrymandering.

The unanimous three-judge panel, which included one Republican, found that the North Carolina Constitution's mandate that elections be "free" means they should reflect the will of the voters. "Elections are not free when partisan actors have tainted future elections by specifically and systematically designing the contours of the election districts for partisan purposes," the court said. The right to "free elections" has been in the state constitution since 1776, and its scope was broadened in 1868 and 1971.

The court also ruled that extreme gerrymandering violates the state constitutional rights to freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and equal protection. The judges noted that the state Supreme Court has interpreted these rights to be even broader than federal constitutional rights.

When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June that federal courts couldn't address gerrymandering in North Carolina, calling it a "political question" outside their jurisdiction, the opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts acknowledged that state courts could address the problem through state constitutions. The high courts in Florida and Pennsylvania have struck down election maps for partisan bias in recent years.

Though North Carolina legislators tried to make the case that the state court lacked authority to strike down the maps, the court rejected those arguments. Quoting a 1787 state Supreme Court ruling, the judges said that if courts couldn't strike down unconstitutional laws, then lawmakers could "render themselves the Legislators of the State for life, without any further election of the people."

End of an era

The court noted that its ruling comes "as we near the end of the decade, and with another decennial census and round of redistricting legislation ahead." Without judicial intervention, it said, the legislature's current maps would almost certainly keep the Republican majority in charge after the 2020 election.

The judges justified the tight two-week timeline for redrawing by citing legislators' delays in previous gerrymandering cases. They mentioned the "Hofeller files," documents found on the hard drives of a deceased Republican redistricting expert that revealed legislators misled a federal court to avoid a special congressional election in 2017 with maps that weren't racially gerrymandered.

The federal court did order new maps that didn't discriminate against black voters. But according to author and activist Dave Daley, who obtained the Hofeller files, the documents "raise new questions about whether Hofeller unconstitutionally used race data to draw North Carolina's congressional districts" after the 2016 court order.

Daley said the new files also suggest that Hofeller worked with North Carolina Republicans to racially gerrymander judges last year. The new judicial election districts in Charlotte are now the subject of a racial gerrymandering lawsuit in state court.

Rick Hasen, an election law expert at UC-Irvine, responded to last week's partisan gerrymandering ruling by asking if there's enough time to bring a similar lawsuit in state court challenging North Carolina's gerrymandered congressional districts before 2020.

The court would need time for a trial, but the judges probably wouldn't be starting from scratch. The North Carolina Supreme Court, which has had a Democratic majority since 2017, assigned the same three-judge panel to hear previous redistricting cases. And the constitutional issues would be largely the same as in the case decided last week.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.