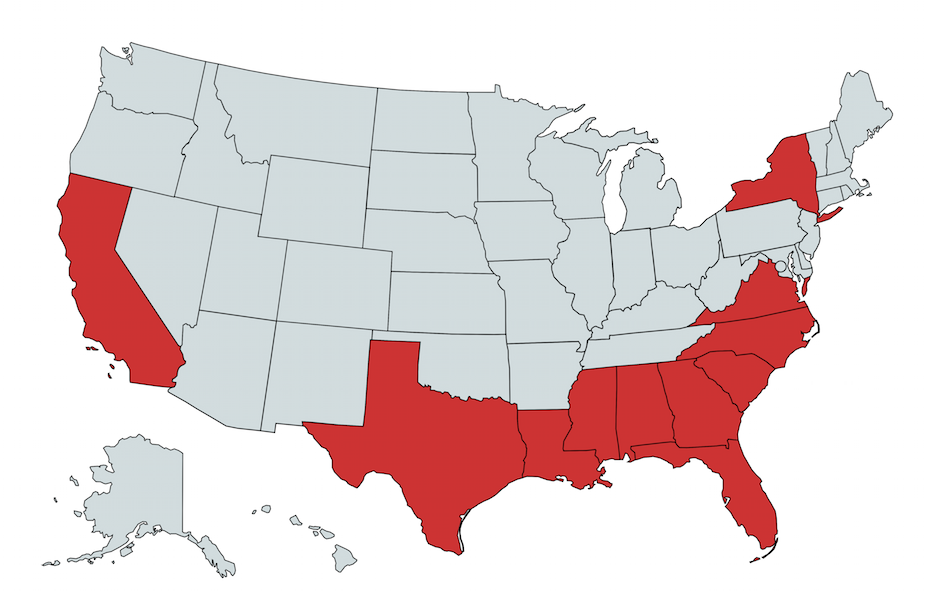

The states facing federal preclearance under proposed Voting Rights Act fix

U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell's bill to restore the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which the U.S. Supreme Court gutted in a 2013 ruling, would require 11 states with a history of voting discrimination, shown here, to submit any proposed election changes to the U.S. Department of Justice for preclearance.

Last week marked 54 years since Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama, when African-American voting rights marchers were brutally assaulted by law enforcement officers while crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The televised event shifted public opinion and galvanized Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).

On the event's March 7 anniversary, U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York, the chamber's minority leader, renewed his party's call to restore through legislation the sections of the VRA that required states and counties with a history of voter discrimination — most of them in the South — to get federal preclearance for election changes.

The U.S. Supreme Court effectively struck down the preclearance provision in its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder ruling in a case involving an Alabama county that no longer wanted to comply with its requirements. The court agreed with Shelby County's arguments that the VRA's preclearance coverage formula was unconstitutional because its criteria were outdated and led to Southern states disproportionately bearing the preclearance burden. Since the decision, many Southern states have implemented restrictive new voting laws.

"Last year, we saw examples of voter suppression disproportionally targeting communities of color in the midterm elections, and thanks to the Supreme Court's Shelby County decision, we have fewer tools to fight back," Schumer said in a press release.

The current Congress is now considering legislation that would restore the VRA. Last month, Rep. Terry Sewell, an Alabama Democrat who represents Selma, introduced the Voting Rights Advancement Act (H.R.4), which would update the preclearance provision. The legislation has been reintroduced in every session of Congress since 2015, when Sewell originally introduced it. H.R.4 currently has 207 co-sponsors, 45 of whom represent Southern states. No Republican members have signed on to date.

At the time it was struck down by the Supreme Court, the Voting Rights Act's preclearance formula covered jurisdictions that had voter registration or turnout rates below 50 percent in 1964 and had employed discriminatory devices to discourage voting, like literacy tests. Jurisdictions were also allowed to "bail out" of preclearance if they could prove no voting discrimination for 10 years. That formula covered nine states as a whole: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia. It also covered dozens of counties and municipalities in other states, including California, Florida, Michigan, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina and South Dakota.

Sewell's H.R.4 sets out a new formula that the U.S. Department of Justice would use to determine which states need federal preclearance of election changes: those with 15 or more voting rights violations during the past 25 years, and those with 10 or more violations if at least one was committed by the state itself. Under that formula, 11 states would be subject to preclearance, most of them still in the South: Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia.

When Sewell originally introduced her bill in 2015, other legislation that would have restored the preclearance provision was also introduced. The Voting Rights Amendment Act was sponsored by Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner, a Wisconsin Republican, and had bipartisan support. Less stringent that Sewell's bill, it would have brought under federal preclearance all states and jurisdictions with five or more voting violations in the past 15 years. The bill stalled in the legislative process because of inaction from Republican leaders.

On the day Sewell reintroduced the Voting Rights Advancement Act, standing at her side was U.S. Rep. John Lewis. The Georgia Democrat and longtime civil rights activist was beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday and suffered a fractured skull and is now among the bill's co-sponsors in the current Congress.

"We've come too far, and made too much progress to go back," Lewis said at the legislation's unveiling. "With this piece of legislation, we will continue to go forward."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.