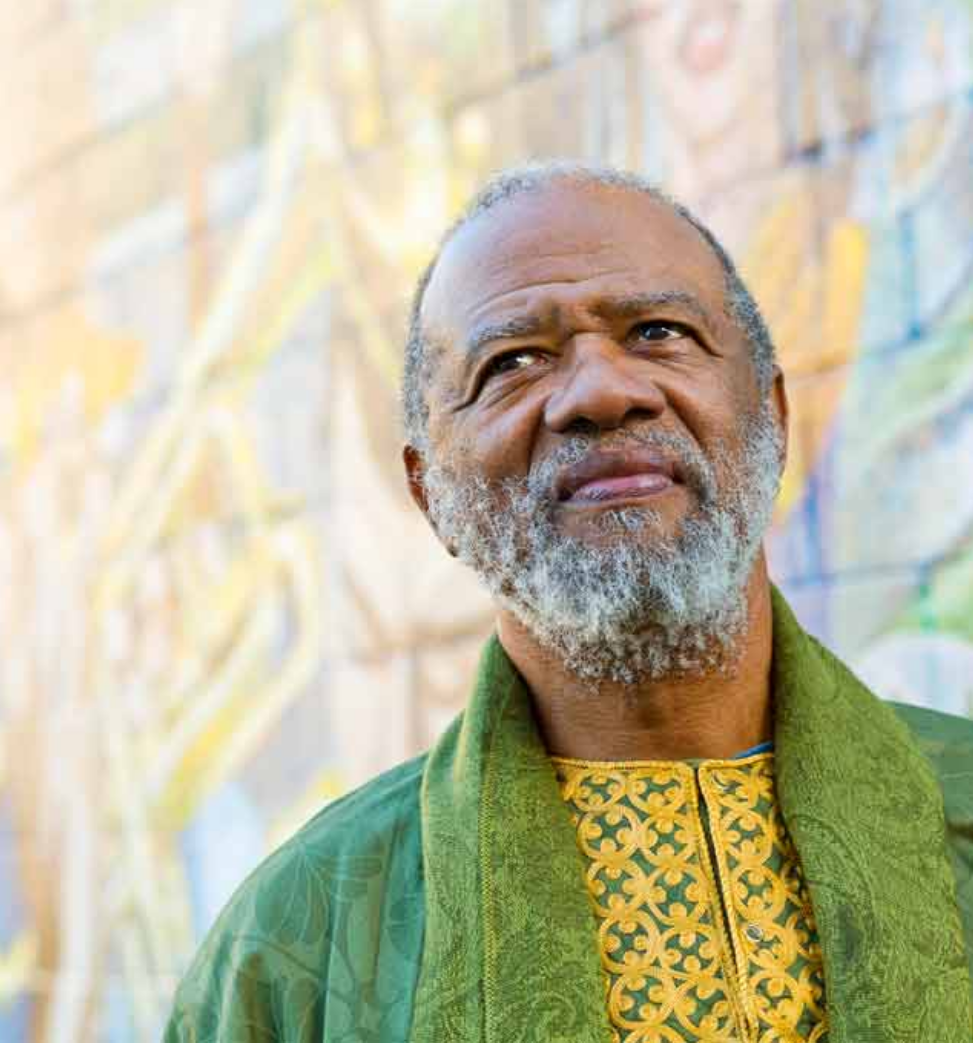

Remembering John O'Neal: Storytelling for change

John O'Neal brought performance and storytelling to his work as an organizer in the civil rights movement, and he continued fusing culture and activism until his death in New Orleans in February. (Photo from Junebug Productions.)

John O'Neal was a playwright, actor, storyteller, educator and community organizer — and, as he once told me, "they're all similar, and part of the same thing." O'Neal passed away on Feb. 26 in New Orleans, his home base since the mid-1960s for creating a unique blend of culture and activism that lifted up the voices of ordinary people and helped them see that they, too, could be agents of social change.

After earning bachelor's degrees in English and philosophy from Southern Illinois University in 1962, O'Neal came South to join the black freedom struggle. He became a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Georgia and Mississippi, and a leader of the Mississippi Freedom School project in the summer of 1964.

It was in October of 1963 that O'Neal, along with civil rights compatriots Doris Derby and Gilbert Moses, founded the Tougaloo Drama Workshop at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, which eventually became the Free Southern Theater. Dubbed a "cultural arm of the movement," the Free Southern Theater came with O'Neal to New Orleans in 1965, where it lasted until 1980 in carrying forward its mission "to use theater as an instrument to stimulate the development of critical and reflective thought among Black people in the South." After the theater closed, O'Neal opened Junebug Productions, which continues to use performance and storytelling to engage and sustain people in the work of social change.

O'Neal was close to the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South. For more than a decade, he wrote a popular column for the Institute's print journal, Southern Exposure, under the pen name Junebug Jabbo Jones. In a fascinating 2012 video, O'Neal relates that the name was inspired by Dr. Junebug Jabbo Jones, a fictional figure Howard University students used to ridicule pompous professors. But O'Neal turned the character on its head, transforming Junebug into a storyteller of humble background whose homespun observations offered a piercing look at the reality of black life. As O'Neal's daughter, Wendi Moore-O'Neal, said: "Junebug Jabbo Jones represented the wisdom of common, everyday black people, how black people have used wit to survive. I see him as a (fictional) folk hero of the civil rights movement."

Below is the first Junebug story that I published when I became editor of Southern Exposure in 1997. It's a searing, unforgettable story, capturing the essence of O'Neal's approach: using wry humor to introduce topics that are deadly serious; drawing on the storytelling tradition to open a window to real-world social injustices; a belief that every person has a story to tell, from which all of us can learn. The Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans will be hosting a "homegoing celebration" for O'Neal on March 30.

* * *

Junebug Jabbo Jones: Silence Is Golden

When I was a kid, my daddy used to tell me all the time, "Silence is golden. Be rich!" When I had my mind set on something and couldn't get the answer I wanted, my mother would tell me, "Boy, I believe you'd argue with a sign post!"

Now that my old lady and me have a bunch of nieces, nephews, and a grandchild of our own, I reckon that I have an idea of what they had in mind. Still, I have to say that it somewhat depends on what brings on that silence.

For instances, this lady named Mrs. Annie Albritton from back in Four Corners where I grew up had asked me to come to her family reunion to tell stories and to get her family members to tell their own stories. One of Mrs. Bright's cousins told a story about her husband that I haven't been able to get out of my mind.

It was late at night and she hadn't said anything in the group that had met earlier, but she had definitely caught my attention. She was sitting on the screened-in porch of the lodge where the reunion was being held. I went out and asked her why she hadn't said anything when we were telling stories. She said she'd enjoyed the stories that everyone else had shared but that she didn't think she had much to say. She said she'd recently lost her husband and that was all she could think about. Right away, I figured she had one hell of story to tell.

I told her I'd really like to hear her story if she'd like to share it. Listening to her was like watching a movie.

Her name is Louise Bright. She's a little, fine-featured woman but seems like she'd be tough in a fight. She showed us a picture of her late husband, Mr. C. J. Bright. He was a large, dark-skinned man with a bald head and a full, deep, well-satisfied smile. I wrote the story up and asked her if it'd be alright for me to share it with you. She said she liked the way I wrote it out so here it is, in her own words.

* * *

I believe Mr. Bright loved me almost as much as he loved life. I knew him as well as you can possibly know another person. We would have been married 36 years on this coming June 28th. I don't believe he ever lied to me — there were a couple of times when I wished he had … lied … believe you me. He had a silver tongue. You just couldn't stay mad with him.

We graduated together from Dusable High School on a Saturday. We got married the next Tuesday and he shipped out for Lackland Air Force Base for basic training that next Monday. Michael, our oldest, was born that December on Christmas Eve.

He was surprised by the white people; we'd never gotten to know any of them in Chicago. If you didn't do housework or yard work, you didn't have nothing to do with them.

He was particularly surprised by the Southern whites. "Crackers" we used to call them. The surprising thing about them was how … nice they could be, after you got used to their accents. They were some of his friends. But after we retired and got this little house here in St. Pete we didn't have occasion to see any of them anymore.

See, he had been there when the cops broke down the door with their guns drawn. They had knocked him down when he asked them what they were doing. He was watching when our little 13-year-old grandchild came out of his room to find out what all the noise was about. He was watching as the three cops told little Timmy to "take the position." He was screaming, "What are you doing in my house with those guns?" He was knocked back to the floor as one of the cops said, "Make that old nigger shut up! Get your hands up, boy!" "What's going on?" Timmy wanted to know. "You're under arrest; suspicion of drug trading! I said keep your hands up, boy!" "Do what he says, Timmy. Do you all have a warrant?" "I told you to shut up, nigger!" "Leave my grandpa alone!" "You keep your hands up!"

My husband was watching as Timmy reached down to pull up his baggy pants to keep them from falling. He was watching as that young white policeman squeezed off the one round that tore a hole in Timmy's chest big enough to stick your fist into. He was holding little Timmy in his arms when the life went out of him, without enough air in him to get the question, "Why?" from his eyes to his lips.

Watching was just about all Mr. Bright did for the next three years while the case drug from one court to the next. All he did was watch. He just about quit talking. But when the cop walked out of that courtroom free and clear, something snapped inside him. I heard it just as plain as a bat against a ball.

That morning I know something was wrong. He hadn't kissed me in three years. He said, "Good bye, baby." I said, "Where you going?" He said, "I'm going to see if I can find some justice." I didn't even know he had a gun.

He killed the judge and seven other people before they shot him down. He didn't even try to defend himself. The silence had built up in him till the dam just had to break.

He was a good man.

I love him still.

* * *

Shamelessly she wiped the tears from her cheeks with the dainty little handkerchief that had been folded neatly in her lap when she started the story. We sat together for a long time listening to the crickets and looking at the bright shining stars in the south Mississippi night.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.