Patchwork

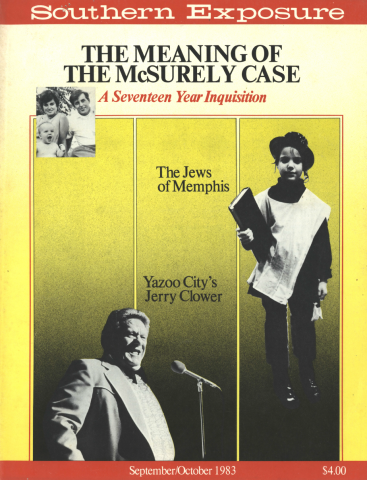

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

Patchwork Oral History Project came about in bits and pieces — beautiful, bright experiences stored in my mind, sometimes of no apparent use, but too precious to throw away. I remember sitting on a wooden swing in August with Mommee, my maternal grandmother, shelling butterbeans from her garden and eating cool sweet watermelon in the backyard with my paternal grandmother, Nanaw. These times were my initiation to the wisdom of our foremothers. Later, walking through the heavy perfume of our old family friend Louise Jones's flower garden, I learned the stories of a black culture — as fearsome and exotic to me as the great eye of the zodiac hanging above Louise's bed. Gradually, these experiences began to accumulate and when I set about piecing them together, took on a new life of their own. Patchwork, a memory quilt of many hues, came to be a living project.

During the 1970s and the resurgence of the women's movement I began to realize how vital it is to appreciate the experience of women who have come before us. They have prepared the earth for our future gardens. By now it is almost a cliché to say that women's contributions, though mammoth, have been ignored in our society. And yet by dismissing the statement as a cliché, society tends to obscure the continuing reality that a woman's contribution is not considered as important as a man's.

Woman's role has changed, to be sure. We can dream bigger dreams — sometimes we can make them come true. But our foremothers lived in a different world. Men made history; women made do. That was the reality of their lives. And it's the making-do that fascinates me — taking life as it comes, making the best of it, and enduring. So I decided to concentrate on women in my oral history project and chose the name Patchwork to epitomize the strength and beauty of women's lives — scraps of homespun cloth joined together to create an aesthetic delight for the soul and a practical comfort for the body.

Stories of our grandmothers give us a look back to a time long past, a world dramatically different from our own. They also give us a look inward, revealing a personal history inherited from them which influences our way of looking at and living in this changed world. Each of us can trace a particular way of speaking, a certain style of cooking, an individual concept of life to our foremothers.

Some of our recollections tell the same story. Country folks, black and white, share the same memories of farm chores, homegrown food, and neighbors helping each other. Yet, as Southerners, we are still divided in our perspective on the Civil War. Whites tell of Northern aggression: the rich of lost plantations and stolen silver, the poor of confiscated livestock and contaminated food. Blacks tell of grandmothers who were slaves, and of the time when freedom came.

I started recording conversations with older women on a random basis, beginning with a dear friend, Elizabeth Cousins Rogers, who is 92 this year. (See "Stepping Stones,'' Southern Exposure, Vol. X, No. 2.) Elizabeth operated a Red Cross canteen in Europe in World War I, married a flyer, knew the bohemian Paris of the 1920s, divorced, became an editor at Vogue magazine, began organizing labor unions during the depression, married an ex-Wobbly, and has spent her life as a dynamic political activist. Her heroism set me afire.

No less inspiring are women who "only " raised a family, struggling with as many as a dozen children, often alone, with money always scarce. They came through life weaving a strong fabric of love and faith.

I'm frequently met with the exclamation, "Oh, there's nothing interesting to tell about my life. " It's never been true. A few well-chosen questions will spark memories long put away. So we spend hours together, both transported to yesterday, each laughing and crying over people and times gone some 50 years and more. Sorrow is never forgotten, old joys are always with us.

I'm not usually so much interested in the dates and names vital to straight documentary techniques as I am in the emotions and philosophies. Why people lived the way they did and how they felt about their lives provides the basis for all that they accomplished in life. To my mind, feelings as well as facts are the essence of a good oral history. So, through the years I've learned to listen more and question less. I find that questions are usually answered in the interviewee's own good time and always more fully than if I had interjected the question myself.

In Patchwork, time is the teacher, yet it is also an enemy. I always work with a sense of urgency, to capture our past before it's too late, to catch women before they go on, leaving us with questions unasked, unanswered.

Included here are selections from Legacy, a larger work in progress dealing with memories of our grandmothers. It is dedicated to my grandmothers, Mary Una Jones Fory and Bertha Lee Roberts Gilbert Heard.

Mable Wiggins

Mable Wiggins grew up with four generations in one home. She talks of the seasonal farm chores in the country: hog killing, molasses making, digging out the water wells, log rolling, and quilting bees. "Just families a-helping families, that's the way they did it back then, to get big jobs done. That's the only way it could be done." Mable, her great-grandmother Sally McDaniels, her grandmother Eliza Finger, and her father lived in a farm house in Harding County, Tennessee.

It was a hard thing for me to realize, that I had two old, old ladies and I didn't have a mother. They told me my mother was gone, or that she was dead. I was supposed to understand what dead was, and I didn't. And why, if she was gone, didn't she come back sometime? See, a child's way of thinking. But she just wasn't there and I felt, just a gap — of something's gone.

Great-grandmother Eliza used to sit in the corner and smoke a cob pipe. I remember when my grandmother would get after me about something, my great-grandmother would whisper, "Come here, Mable." I'd go and she'd hug me up and that just fixed it all. That hugging from her, that tender love that was missing, I guess, from Mother. But my grandmother never had nothing like that.

Grandmother Eliza was the caretaker of the family, working all day long, all year round. As Mable says, "That's just what it took to please her — she was 'making family go. '"

Her hair was dark brown, she never cut it. People was always talking to her about her hair. "Tell us your recipe," they'd say. When she washed it, she'd sit out on the back porch and have a little tub sitting up there and have wash water in it and rinse water in another one. She'd just throw it all down there and just wash it like she was washing clothes. I'd just get fascinated sitting around watching just what she'd do to it. On that same porch the sun would come in good and she'd sit there and sun dry it. It would take a long time to dry all that stuff. And I was such a tiny thing, I was in awe about seeing what I was looking at.

Mostly we used the soap that she made. We had a fireplace and we'd burn hickory and oak — hardwood, you know. Every day we'd clean out the ashes and put them in a wooden barrel out in the back yard. When she'd get the barrel up about two-thirds full, she'd start putting water in there and put a drip pan under this elevated base it was on and it would drip out through the barrel and it would be lye. It's strong and dark, almost like iodine. And the hog killing time would be once a year, when it was cold weather because we had no refrigeration. She'd take the lard from the hog meat and then boil this lye in there and the lard and the lye come out to be soap. There was such of a trick to it.

She'd wash clothes with a tub and the washboard sitting in that and there'd be a little jar of the soap. You'd reach your hand down and rub that soap on the dirty clothes like a coat of jelly. And boy, would it suds! It would take the skin off your fingers, it was so strong with lye. You needn't not go to wash with no delicate fingers cause you'd have them skinned to the bleed.

We'd grow and can the vegetables, and then we had fruit that growed in the orchards and we'd take it out in the sun and let it dry. We'd dry beans. We made our own meal out of corn, we'd take it to the grist mill and have it ground into meal.

I heard somebody talking to her about the Civil War. How when the soldiers come through, they'd break into the house, pour out the molasses and sugar, drag the meat in the dirt — all kind of crazy things. She told about weaving. She was making some cloth to make her menfolks' clothes. She's sitting out in the yard, so she could see. If the soldiers was to come, she was going to hide it. They came and she jumped up and hid it under a big flowerbush.

They had quilting parties going pretty well all the year. We raised the cotton, picked it, took it to the gin to get the seeds out of it, and then we'd card it on combs and make it into batts to go in the inner linings of quilts they had pieced. They had quilting frames hanging from the ceilings or on chairs. In between the other chores, they had quilts rolled up, waiting for them to have time to do a few more stitches. All the neighbors would get together and go in and quilt out somebody's quilt. And they'd go to somebody else and do theirs, and just go all the way around the community. In the winters you'd pile five and six quilts on top of you at a time in the nighttime — and then you'd still get cold!

My grandmother, she had her way about sewing. When I'd go to school, I'd see others how they had their clothes made. She didn't make mine like that. Well, I wanted her to let me sew. One day, she had the patterns all spread out, material cut out, and she had to go start some cooking in the kitchen. When she got away from that pattern, where the nick would be left up high, I got the scissors and I cut it way down this a-way! She come back to it and found it all cut and she says, "Now, if you can do this, you can just finish it now!" I learned to sew from that.

I remember when great-grandmaw died, she was 96. They called it dropsey, it was fluid. It was like she was drowning. She died in early morning. My cousin come and waked me up and said, "Grandmaw's passing away, don't you want to get up?" I still didn't understand what she meant when she said she's passing away. But I got up and was holding her hand when her head dropped and her last breath came.

The women of different families of our neighbors come together and made her some new clothes that they buried her in. Each one was doing some different part of the dress. It just fascinated me how fast they put it together. They didn't hold the bodies out that long.

But in a way I was scared of what they was doing to her. I was thinking now, what if she was just asleep and not dead? What if she's not dead and they're putting her down in that deep hole? I couldn't get rid of that. W

ell, now, I've told off a great big rigmarole I didn't know I knew.

Hilda Murdock

Hilda Murdock takes pride in the fact that her family is well educated. "We had doctors and lawyers and ministers, even in the old times. They were very strict about us respecting other people's rights. And they always taught us to let each tub — I'm telling you like they told me — let each tub stand on its own bottom."

My great-grandmother Priscilla Smith said her people always worked in the boss's house. So I think that is one of the reasons why they were educated. The children would teach them to read and write. In a way they thought they were more than the rest of the slaves because they had to be kept clean to work in the house. She said she'd wear this big white rag on her head with these white aprons, and she would wear all these petticoats that had to be starched. So the other slaves sort of envied them, you know.

She said they had to sneak in the woods somewhere and have church service. They didn't allow them to have church. The boss man, see, was supposed to be the God. So all in all my family was very religious from the slaves on down to us.

My great-grandparents jumped over the broom. She said they had a big ceremony and somebody played the guitar and somebody played the harp and the preacher says, "Now!" and they jumped over and hugged and kissed and were pronounced man and wife. But my great-grandparents, being as civilized as they were, he being educated, they repeated the marriage vows. They repeated and everybody thought they were smart, you know. They went on to do pretty good after freedom because we still have some property in Terrebonne Parish that they bought. He bought enough to give some to build a church. My great-grandfather could read a Bible. My great-grandmother couldn't, but late in her life the government had this project and she went to school. She wrote us all a letter before she died.

Grandmaw Priscilla came to my house about a month before she died. She was in her late 90s and had to walk eight blocks. She was very spry, always jumping around. She liked a little wine and my husband would sneak and buy it for her. She pulled up her dress and danced the reel for us. She told us how she used to raise up her dress and take out her cane knife and go down to the quarters — that's what they used to call where they lived then — to get grandpaw from some lady's house. They stayed together — died together — but she was frisky and he was frisky. They had their funerals in the church that they built, and were buried in the church grounds.

My grandmother was Mary Smith Hall. We called her "Mama." She always had the house full of children. All our friends were her children. For each one of us grandchildren, she had 10 more. The main thing about her was her religious beliefs. We all attributed it to our family as having a guardian angel because of her.

Well, this is what happened. One of my aunts was blinded when she was two years old, and my step-grandfather would bring her every other week to the hospital in New Orleans. So my grandmother says she was just sitting in the rocking chair one day and the door opened and a big light came in and in this light was a lady, all in white. This lady told her, "Mary, if you want your child's sight back, christen her over and call her Eve." Her name was Eva. Well, they christened her over. She was in New Orleans at the time, and on the way home from the hospital, she got her sight. So we began to believe in this guardian angel. I have never seen her, none of us has ever seen her, but Mama made it so clear to us, you could just see her.

We would make it a point to go to church every New Year's Eve night, from babies on up. And she would have the prayer meeting at her house. We'd all meet there and we'd hide our little bottles under the step, so she wouldn't see us. She would make eggnog and we would spike it. She would pray for us, each and every one of us. So, I still tell everybody that I'm still living on my grandmother's prayers.

We lived a beautiful life with my grandmother. She died here in New Orleans. I can remember, she used to sit on the stoop in the afternoons and she'd throw this big, beautiful towel around her and she smoked a pipe. All the children in the neighborhood would be around her and she'd be telling them tales.

She'd tell how during slavery they would keep my grandfather's grandfather in a cage for hours without food or water because he was always doing something to antagonize the boss. His grandmother would drink water and go to the cage and kiss her husband and put water in his mouth.

Mama was the type of person that everybody brought their troubles to. People still speak of the type of person she was and she's been dead, oh, Lord, about 40-some years.

Sidonie Benton

Sidonie Benton's grandmother was Augustine Gingery of Donaldsonville, Louisiana. She didn't speak much English and used to get mad at Sidonie because she couldn't speak French. Sid says, "I'm a lazy Cajun from down the bayou. I was born practically in Bayou Lafourche. I can tell you something about me. When I was three years old, they tell me, I was a sickly kid. The doctor came one evening and told my mama that I'd be dead by morning. So rather than have my mama get in the coroner, he wrote my death certificate. My papa went to the cemetery and had the family tomb opened for me. My brother used to call me 'Tomb Dodger' til my mama heard him."

My grandmaw tells the tale about how the Union soldiers came in to investigate — and grab whatever they could grab, that's the way they told it to me. They got to what we called the bibliotheque, the bookcase, and one of them took out his sword and broke one of the glass doors, just for meanness. And they took the comb right out of her hair. Our eyes would get that big, listening to her tell it. She was a big woman, she defied them terribly, I believe.

Now, years and years later, my sister got that bibliotheque, and she had it repaired. That glass had stayed broken all those years!

Grandmaw and Grandpaw owned the whole square of ground right on the main street. One night Grandpaw heard a lot of commotion the horses were making and got up to see. They shot him and killed him. It was Union soldiers. Grandmaw being the kind of woman she was, went out of the great big long back porch to see what the noise was about. It was dark and she tripped over his dead body.

She was bitter about the Civil War — she didn't have any slaves. And, well, she was mad as hell. The reason why I say that is because in French she called the Yankees "beasts."

After the war, they had nothing, you know. She sold one piece of land at the time and I imagine that's how they lived.

Grandmaw used to tell her grandsons who were young that Grandpaw had buried the silver during the war. She always had a vegetable garden and Grandmaw would get that garden dug up every year. They were looking for the silver!

Oh, damn Yankees, I hated them! Course that's all gone, now. I don't feel that way at all now. But down South we still say damn Yankees.

Annabel Gros Feigel

Annabel Gros Feigel was one of 16 children, born in Donaldsonville, Louisiana, and raised in New Orleans. Her grandmother, Virginia Guidry, was born in 1843 of wealthy parents and educated in France. In later years she lived on a widow's pension from the Civil War. Annabel, her grandmother, her parents, and her brothers and sisters all lived together.

My grandmother didn't have a nice disposition, she really didn't. I mean, I can't lie about it, as I recall it you know.

She had owned a home in Clottsville, Louisiana, on Bayou Lafourche and a pretty home at that. My uncle, he got kind of, you know, a little money hungry. He went and sold the house from under my grandmother's feet. Then he didn't want her after that. He kept her for a couple of months, you know, the usual thing, and then she came to live with us.

I think my grandmother had really gotten hurt when she had to move out of her house. She didn't like New Orleans and I think she would have wished to be back in the country, where she was born and raised. They'd had acreage, a garden, a cow, everything for their living. She had so much. But of course then, when she moved with my parents, everything was gone, more or less. That house was vacant for a long time and my grandmother used to go back there and spend time.

We used to call her Memere, that was French. She did nothing, nothing. She sat on that rocking chair on the porch from morning to night. She had no friends. Watched, that's all she did.

Another thing, my grandmother hated my sister Virgie with a purple passion. I kind of stayed away from her, but Virgie was a son-of-a-gun, she could care less. Virgie used to do "Alaria," you know. It's a ball game — you throw the ball up and your leg goes over the ball and you'd say, "One two, three, alaria, four, five, six, alaria," and so on. She loved to play it. So she would play that around my grandmother and Memere would sit there and wait for the opportunity for Virgie to throw that ball down. When Memere died, my mother found 50 balls in her trunk that she had taken away from Virgie. She couldn't stand for Virgie to play ball around her! In those days you could get a ball for a penny. I don't know wherever Virgie got all those balls; maybe my mother would give her a penny and she'd go buy a ball instead of a piece of candy. Fifty balls my mother found in that trunk! Yeah, she was really mean.

Memere got very, very sick, and she lay on the bed many months, maybe a year. My mother had to take care of her. We slept right there in the room with her. Then when she died, I remember it as if it was yesterday. The embalmers came in with their buckets and all — it was horrible! We lived in a two-story house and they carried her stiff body down the steps and then they laid her on that cold slab. They waked her in the house.

I really got bad memories of this woman. Isn't that awful? It's a shame to be talking about a person like that when they're in their grave. But you just don't lie.

When I think back, I think it was that she was uprooted. It might have been her unhappiness that made her act that way. You just can't uproot old people.

Olga Roos Brooks

Olga Roos Brooks visited her grandmother Elizabeth Roach in New Orleans every summer to be near her childhood sweetheart. She eloped at age 15 and she and her husband joined a traveling vaudeville troupe, later getting parts in silent movies. She almost didn't get married at all, because when the first minister they tried asked her if she had relatives to vouch for her age, she naively replied, "Oh yes, I have my grandmother, Mrs. Eugene Roach. " The minister replied, "My God, that's my best friend, she sings in our church. I couldn't think of marrying her granddaughter without her present!" She and her sweetheart swiftly retreated, hopped the ferry across the Mississippi River and were secretly married.

My grandmother had a wonderful voice. She was a renowned singer and sang in five different languages. The critics said her voice was greater than Adelina Patti. She sang in concert where Maison Blanche stands today — it was Christ Church Cathedral — when she was only 15 years old.

She had so many offers to go to the Metropolitan Opera Company, but she bore 15 children, nine of whom survived. I remember when I was a little girl, grandmother sang at the Presbyterian Church up on Prytania Street. She was holding my hand and we were going to the church this Sunday morning and she had a black taffeta dress with great big leg-o-mutton sleeves and she rustled along as we walked. I was sitting in the front pew and when they announced that Mrs. Roach would sing a solo, you couldn't hear a pin drop. When she came out, when she sang, the tears just started rolling down my eyes.

And my grandmother was so particular. She was so refined and ladylike. One time I met her in Holmes department store and I was walking down the aisle trying to catch up with her, and I hollered, "Grandma, how are you?" She turned around and said, "Olga, is that ladylike? When you are in public, be sure to speak in a whisper."

I loved my grandmother devotedly. Many years passed and her nine children came to visit her New Year's Eve night, 1919, and asked her to sing an aria from Carmen. She hadn't sung in five years, but her voice never cracked and never broke. She lifted up her voice and she started singing with all her nine children around her. As she did she took this pain in her heart and later that night passed away.

Malle Weathersby

Mallie Weathersby talks of her grandmothers, Fannie Steele Walker and Amanda McLauren as she busily mixes up a skillet of cornbread for her daughter and newborn grandson. Mallie and both of her grandmothers are from a little town called Pineola, Mississippi. "Life was hard, but then, it didn't seem hard because that was what you had to do, just to live, and everybody seemed to enjoy it. It was just like neighbors in the community — there'd be a white family here, maybe the next house would be a black family. But yet and still, when it come work time all of those families took an interest in each other. They called it 'Working through and through.'"

Now, my grandmother Fannie, I hadn't ever met anybody as clean as she was. Her main trouble was trying to keep clean.

You see, back then, people didn't clean house but twice a year. If it was too cold for Christmas, they'd wait til springtime. But most of the time, it was revival time in August. They didn't call it revival in them days, they called it "protract-a-meeting."

The way she would clean her house was to boil big pots of water and take a big gourd dipper full of lye soap and put it in the pot and then clean from top to bottom. Them walls would almost sparkle, you thought they could talk to you. Her floors, they just had the board floors. When she got ready to rinse that floor, she'd rinse it until the water that run off look like you could drink it, it'd be so clean. Absolutely, she'd work you to death.

And she'd make some powerful lye soap. We'd have to go in the woods, where cattle had died, take the bones and put them in the soap pot. That lye in that pot would eat those bones up, they would disappear. And then she would test it. She would get a feather from a chicken and stick it in there and take it out and if it eat those fringes off, it was too strong. My granddaddy's overalls, she would rub them white. Absolutely the truth, they looked like they had been coated with Clorox — and it would be nothing but her fist on that washboard.

And would she fuss if there'd be some dirt on my dress. Oh, my goodness, she'd want to strap me up! I don't ever remember her strapping me, but she'd want to. She'd say she was going to put the whippings on the shelf — she'd save them for you.

Mallie has vivid memories of the quilting bees at her Grandmother Mandy's house.

The ladies would gather in the evening and my goodness alive, they could really do some neat quilting. They mostly did it at my grandmother's house because Mandy didn't have no children and all the other ladies had children around and they'd be under the quilt, bumping heads, you know. They'd say, "You going to get your head cracked with a thimble!" I got mine cracked a many a day.

My grandmother could piece some stars. I'm going to tell you right now. It wasn't shabby, not a bit. It was up-to-date. She had the double wedding ring. I don't know how long it took her to piece it, but when she quilted it, it was some beautiful.

And I did hate it, I did hate cutting up material in those little bitty pieces and then sewing it back together. It didn't make sense to me — while they were together, let them stay together. If I could take big squares of material, put them on the machine and sew them up, I had plenty quilts. They wasn't beautiful, but I told them mine kept me just as warm as theirs.

My grandmother like to fish, and sometimes she would go and she would have her work in her apron. She would be sitting down on the riverbank and she would take and stick them poles right in the bank. She would put her leg across that pole, and when the fish bit it, she'd know. All the time, be sitting up there piecing them scraps.

Back then, it didn't mean so much to me, but now it does. It really means something to me to think about how interesting she was.

Tags

Dee Gilbert

Dee Gilbert is a free-lance writer living in New Orleans, and the director of Patchwork — An Oral History Project. (1983)

Dee Gilbert is a New Orleans free-lance writer and coordinator of the New Orleans Women’s Oral History Project. (1982)